Stefaan Verhulst

Paper by Nick Couldry and Alison Powell in the Journal Big Data and Society: “This short article argues that an adequate response to the implications for governance raised by ‘Big Data’ requires much more attention to agency and reflexivity than theories of ‘algorithmic power’ have so far allowed. It develops this through two contrasting examples: the sociological study of social actors used of analytics to meet their own social ends (for example, by community organisations) and the study of actors’ attempts to build an economy of information more open to civic intervention than the existing one (for example, in the environmental sphere). The article concludes with a consideration of the broader norms that might contextualise these empirical studies, and proposes that they can be understood in terms of the notion of voice, although the practical implementation of voice as a norm means that voice must sometimes be considered via the notion of transparency”

White paper by Granicus.com: “Open government is about building transparency, trust, and engagement with the public. Today, with 80% of the North American public on the Internet, it is becoming increasingly clear that building open government starts online. Transparency 2.0 not only provides public information, but also develops civic engagement, opens the decision-making process online, and takes advantage of today’s technology trends.

This paper provides principles and practices of Transparency 2.0. It also outlines 12 fundamentals of online open government that have been proven across more than 1,000 government agencies throughout North America.

Here are some of the key issues covered:

- Defining open government’s role with technology

- Enhancing dialog between citizen and government

- Architectures and connectivity of public data

- Opening the decision-making workflow”

at BCG Perspectives: “Getting better—but still plenty of room for improvement: that’s the current assessment by everyday users of their governments’ efforts to deliver online services. The public sector has made good progress, but most countries are not moving nearly as quickly as users would like. Many governments have made bold commitments, and a few countries have determined to go “digital by default.” Most are moving more modestly, often overwhelmed by complexity and slowed by bureaucratic skepticism over online delivery as well as by a lack of digital skills. Developing countries lead in the rate of online usage, but they mostly trail developed nations in user satisfaction.

Many citizens—accustomed to innovation in such sectors as retailing, media, and financial services—wish their governments would get on with it. Of the services that can be accessed online, many only provide information and forms, while users are looking to get help and transact business. People want to do more. Digital interaction is often faster, easier, and more efficient than going to a service center or talking on the phone, but users become frustrated when the services do not perform as expected. They know what good online service providers offer. They have seen a lot of improvement in recent years, and they want their governments to make even better use of digital’s capabilities.

Many governments are already well on the way to improving digital service delivery, but there is often a gap between rhetoric and reality. There is no shortage of government policies and strategies relating to “digital first,” “e-government,” and “gov2.0,” in addition to digital by default. But governments need more than a strategy. “Going digital” requires leadership at the highest levels, investments in skills and human capital, and cultural and behavioral change. Based on BCG’s work with numerous governments and new research into the usage of, and satisfaction with, government digital services in 12 countries, we see five steps that most governments will want to take:

1. Focus on value. Put the priority on services with the biggest gaps between their importance to constituents and constituents’ satisfaction with digital delivery. In most countries, this will mean services related to health, education, social welfare, and immigration.

2. Adopt service design thinking. Governments should walk in users’ shoes. What does someone encounter when he or she goes to a government service website—plain language or bureaucratic legalese? How easy is it for the individual to navigate to the desired information? How many steps does it take to do what he or she came to do? Governments can make services easy to access and use by, for example, requiring users to register once and establish a digital credential, which can be used in the future to access online services across government.

3. Lead users online, keep users online. Invest in seamless end-to-end capabilities. Most government-service sites need to advance from providing information to enabling users to transact their business in its entirety, without having to resort to printing out forms or visiting service centers.

4. Demonstrate visible senior-leadership commitment. Governments can signal—to both their own officials and the public—the importance and the urgency that they place on their digital initiatives by where they assign responsibility for the effort.

5. Build the capabilities and skills to execute. Governments need to develop or acquire the skills and capabilities that will enable them to develop and deliver digital services.

This report examines the state of government digital services through the lens of Internet users surveyed in Australia, Denmark, France, Indonesia, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Russia, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the UK, and the U.S. We investigated 37 different government services. (See Exhibit 1.)…”

in AVClub: “Scientists at Facebook have published a paper showing that they manipulated the content seen by more than 600,000 users in an attempt to determine whether this would affect their emotional state. The paper, “Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks,” was published in The Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences. It shows how Facebook data scientists tweaked the algorithm that determines which posts appear on users’ news feeds—specifically, researchers skewed the number of positive or negative terms seen by randomly selected users. Facebook then analyzed the future postings of those users over the course of a week to see if people responded with increased positivity or negativity of their own, thus answering the question of whether emotional states can be transmitted across a social network. Result: They can! Which is great news for Facebook data scientists hoping to prove a point about modern psychology. It’s less great for the people having their emotions secretly manipulated.

In order to sign up for Facebook, users must click a box saying they agree to the Facebook Data Use Policy, giving the company the right to access and use the information posted on the site. The policy lists a variety of potential uses for your data, most of them related to advertising, but there’s also a bit about “internal operations, including troubleshooting, data analysis, testing, research and service improvement.” In the study, the authors point out that they stayed within the data policy’s liberal constraints by using machine analysis to pick out positive and negative posts, meaning no user data containing personal information was actually viewed by human researchers. And there was no need to ask study “participants” for consent, as they’d already given it by agreeing to Facebook’s terms of service in the first place.

Facebook data scientist Adam Kramer is listed as the study’s lead author. In an interview the company released a few years ago, Kramer is quoted as saying he joined Facebook because “Facebook data constitutes the largest field study in the history of the world.”

See also:

Facebook Experiments Had Few Limits, Data Science Lab Conducted Tests on Users With Little Oversight, Wall Street Journal.

Stop complaining about the Facebook study. It’s a golden age for research, Duncan Watts

“The idea of the Good Country Index is pretty simple: to measure what each country on earth contributes to the common good of humanity, and what it takes away. Using a wide range of data from the U.N. and other international organisations, we’ve given each country a balance-sheet to show at a glance whether it’s a net creditor to mankind, a burden on the planet, or something in between. It’s important to explain that we are not making any moral judgments about countries. What I mean by a Good Country is something much simpler: it’s a country that contributes to the greater good. The Good Country Index is one of a series of projects I’ll be launching over the coming months and years to start a global debate about what countries are really for. Do they exist purely to serve the interests of their own politicians, businesses and citizens, or are they actively working for all of humanity and the whole planet? The debate is a critical one, because if the first answer is the correct one, we’re all in deep trouble. The Good Country Index doesn’t measure what countries do at home: not because I think these things don’t matter, of course, but because there are plenty of surveys that already do that. What the Index does aim to do is to start a global discussion about how countries can balance their duty to their own citizens with their responsibility to the wider world, because this is essential for the future of humanity and the health of our planet. I hope that looking at these results will encourage you to take part in that discussion. Today as never before, we desperately need a world made of good countries. We will only get them by demanding them: from our leaders, our companies, our societies, and of course from ourselves.”

As a special project of the Governor’s Mass Big Data Initiative, this report seeks to provide an initial baseline understanding of the landscape of the Mass Big Data ecosystem and its challenges, opportunities, and strong potential for growth.

Through this work, we are pleased to report that the Mass Big Data ecosystem represents an extraordinarily fertile region for growth in data-driven enterprise and offers a unique combination of advantages on which to build the future of our data-rich world.

With strengths across the spectrum of big data industry sectors and in key supporting areas such as talent development, research, and innovation, our region is producing the people, businesses, and products that fuel the explosive growth in this expanding field.

To download the report, click on the image below:

Twiplomacy: “World leaders vie for attention, connections and followers on Twitter, that’s the latest finding of Burson-Marsteller’s Twiplomacy study 2014, an annual global study looking at the use of Twitter by heads of state and government and ministers of foreign affairs.

While some heads of state and government continue to amass large followings, foreign ministers have established a virtual diplomatic network by following each other on the social media platform.

For many diplomats Twitter has becomes a powerful channel for digital diplomacy and 21st century statecraft and not all Twitter exchanges are diplomatic, real world differences are spilling over reflected on Twitter and sometimes end up in hashtag wars.

“I am a firm believer in the power of technology and social media to communicate with people across the world,” India’s new Prime Minister Narendra Modi wrote in his inaugural message on his new website. Within weeks of his election in May 2014, the @NarendraModi account has moved into the top four most followed Twitter accounts of world leaders with close to five million followers.

More than half of the world’s foreign ministers and their institutions are active on the social networking site. Twitter has become an indispensable diplomatic networking and communication tool. As Finnish Prime Minister @AlexStubb wrote in a tweet in March 2014: “Most people who criticize Twitter are often not on it. I love this place. Best source of info. Great way to stay tuned and communicate.”

As of 25 June 2014, the vast majority (83 percent) of the 193 UN member countries have a presence on Twitter. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of all heads of state and heads of government have personal accounts on the social network.

As of 24 June 2014, the vast majority (83 percent) of the 193 UN member countries have a presence on Twitter. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of all heads of state and heads of government have personal accounts on the social network.

Most Followed World Leaders

Since his election in late May 2014, India’s new Prime Minister @NarendraModi has skyrocketed into fourth place, surpassing the the @WhiteHouse on 25 June 2014 and dropping Turkey’s President Abdullah Gül (@cbabdullahgul) and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (@RT_Erdogan) into sixth and seventh place with more than 4 million followers each.

Modi still has a ways to go to best U.S. President @BarackObama, who tops the world-leader list with a colossal 43.7 million followers, with Pope Francis @Pontifex) with 14 million followers on his nine different language accounts and Indonesia’s President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono @SBYudhoyono, who has more than five million followers and surpassed President Obama’s official administration account @WhiteHouse on 13 February 2014.

In Latin America Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the President of Argentina @CFKArgentina is slightly ahead of Colombia’s President @JuanManSantos with 2,894,864 and 2,885,752 followers respectively. Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto @EPN, Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff @dilmabr and Venezuela’s @NicolasMaduro complete the Latin American top five, with more than two million followers each.

Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta @UKenyatta is Africa’s most followed president with 457,307 followers, ahead of Rwanda’s @PaulKagame (407,515 followers) and South Africa’s Jacob Zuma (@SAPresident) (325,876 followers).

Turkey’s @Ahmet_Davutoglu is the most followed foreign minister with 1,511,772 followers, ahead of India’s @SushmaSwaraj (1,274,704 followers) and the Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates @ABZayed (1,201,364 followers)…”

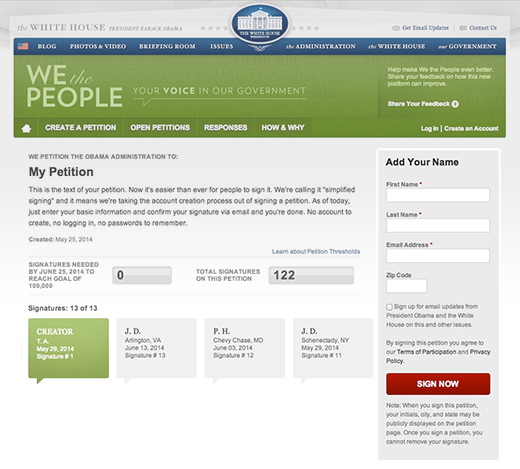

The White House: “With more than 14 million users and 21 million signatures, We the People, the White House’s online petition platform, has proved more popular than we ever thought possible. In the nearly three years since launch, we’ve heard from you on a huge range of topics, and issued more than 225 responses.

But we’re not stopping there. We’ve been working to make it easier to sign a petition and today we’re proud to announce the next iteration of We the People.

Since launch, we’ve heard from users who wanted a simpler, more streamlined way to sign petitions without creating an account and logging in every time. This latest update makes that a reality.

We’re calling it “simplified signing” and it takes the account creation step out of signing a petition. As of today, just enter your basic information, confirm your signature via email and you’re done. That’s it. No account to create, no logging in, no passwords to remember.

That’s great news for new users, but we’re betting it’ll be welcomed by our returning signers, too. If you signed a petition six months ago and you don’t remember your password, you don’t have to worry about resetting it. Just enter your email address, confirm your signature, and you’re done.

Joel Gurin at the SAIS Review of International Affairs: “The international open data movement is beginning to have an impact on government policy, business strategy, and economic development. Roughly sixty countries in the Open Government Partnership have committed to principles that include releasing government data as open data—that is, free public data in forms that can be readily used. Hundreds of businesses are using open data to create jobs and build economic value. Up to now, however, most of this activity has taken place in developed countries, with the United States and United Kingdom in the lead. The use of open data faces more obstacles in developing countries, but has growing promise there, as well.”

The Guardian: “The Los Angeles Police Department, like many urban police forces today, is both heavily armed and thoroughly computerised. The Real-Time Analysis and Critical Response Division in downtown LA is its central processor. Rows of crime analysts and technologists sit before a wall covered in video screens stretching more than 10 metres wide. Multiple news broadcasts are playing simultaneously, and a real-time earthquake map is tracking the region’s seismic activity. Half-a-dozen security cameras are focused on the Hollywood sign, the city’s icon. In the centre of this video menagerie is an oversized satellite map showing some of the most recent arrests made across the city – a couple of burglaries, a few assaults, a shooting.

On a slightly smaller screen the division’s top official, Captain John Romero, mans the keyboard and zooms in on a comparably micro-scale section of LA. It represents just 500 feet by 500 feet. Over the past six months, this sub-block section of the city has seen three vehicle burglaries and two property burglaries – an atypical concentration. And, according to a new algorithm crunching crime numbers in LA and dozens of other cities worldwide, it’s a sign that yet more crime is likely to occur right here in this tiny pocket of the city.

The algorithm at play is performing what’s commonly referred to as predictive policing. Using years – and sometimes decades – worth of crime reports, the algorithm analyses the data to identify areas with high probabilities for certain types of crime, placing little red boxes on maps of the city that are streamed into patrol cars. “Burglars tend to be territorial, so once they find a neighbourhood where they get good stuff, they come back again and again,” Romero says. “And that assists the algorithm in placing the boxes.”

Romero likens the process to an amateur fisherman using a fish finder device to help identify where fish are in a lake. An experienced fisherman would probably know where to look simply by the fish species, time of day, and so on. “Similarly, a really good officer would be able to go out and find these boxes. This kind of makes the average guys’ ability to find the crime a little bit better.”

Predictive policing is just one tool in this new, tech-enhanced and data-fortified era of fighting and preventing crime. As the ability to collect, store and analyse data becomes cheaper and easier, law enforcement agencies all over the world are adopting techniques that harness the potential of technology to provide more and better information. But while these new tools have been welcomed by law enforcement agencies, they’re raising concerns about privacy, surveillance and how much power should be given over to computer algorithms.

P Jeffrey Brantingham is a professor of anthropology at UCLA who helped develop the predictive policing system that is now licensed to dozens of police departments under the brand name PredPol. “This is not Minority Report,” he’s quick to say, referring to the science-fiction story often associated with PredPol’s technique and proprietary algorithm. “Minority Report is about predicting who will commit a crime before they commit it. This is about predicting where and when crime is most likely to occur, not who will commit it.”…”