Stefaan Verhulst

Article by Shen Lu: “China’s National Congress passed the highly anticipated Personal Information Protection Law on Friday, a significant piece of legislation that will provide Chinese citizens significant privacy protections while also bolstering Beijing’s ambitions to set international norms in data protection.

China’s PIPL is not only key to Beijing’s vision for a next-generation digital economy; it is also likely to influence other countries currently adopting their own data protection laws.

The new law clearly draws inspiration from the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, and like its precursor is an effort to respond to genuine grassroots demand for greater right to consumer privacy. But what distinguishes China’s PIPL from the GDPR and other laws on the books is China’s emphasis on national security, which is a broadly defined trump card that triggers data localization requirements and cross-border data flow restrictions….

The PIPL reinforces Beijing’s ambition to defend its digital sovereignty. If foreign entities “engage in personal information handling activities that violate the personal information rights and interests of citizens of the People’s Republic of China, or harm the national security or public interest of the People’s Republic of China,” China’s enforcement agencies may blacklist them, “limiting or prohibiting the provision of personal information to them.” And China may reciprocate against countries or regions that adopt “discriminatory prohibitions, limitations or other similar measures against the People’s Republic of China in the area of personal information protection.”…

Many Asian governments are in the process of writing or rewriting data protection laws. Vietnam, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka have all inserted localization provisions in their respective data protection laws. “[The PIPL framework] can provide encouragement to countries that would be tempted to use the data protection law that includes data transfer provisions to add this national security component,” Girot said.

This new breed of data protection law could lead to a fragmented global privacy landscape. Localization requirements can be a headache for transnational tech companies, particularly cloud service providers. And the CAC, one of the data regulators in charge of implementing and enforcing the PIPL, is also tasked with implementing a national security policy, which could present a challenge to international cooperation….(More)“

Paper by Satchit Balsari, Mathew V. Kiang, and Caroline O. Buckee: “…In recent years, large-scale streams of digital data on medical needs, population vulnerabilities, physical and medical infrastructure, human mobility, and environmental conditions have become available in near-real time. Sophisticated analytic methods for combining them meaningfully are being developed and are rapidly evolving. However, the translation of these data and methods into improved disaster response faces substantial challenges. The data exist but are not readily accessible to hospitals and response agencies. The analytic pipelines to rapidly translate them into policy-relevant insights are lacking, and there is no clear designation of responsibility or mandate to integrate them into disaster-mitigation or disaster-response strategies. Building these integrated translational pipelines that use data rapidly and effectively to address the health effects of natural disasters will require substantial investments, and these investments will, in turn, rely on clear evidence of which approaches actually improve outcomes. Public health institutions face some ongoing barriers to achieving this goal, but promising solutions are available….(More)”

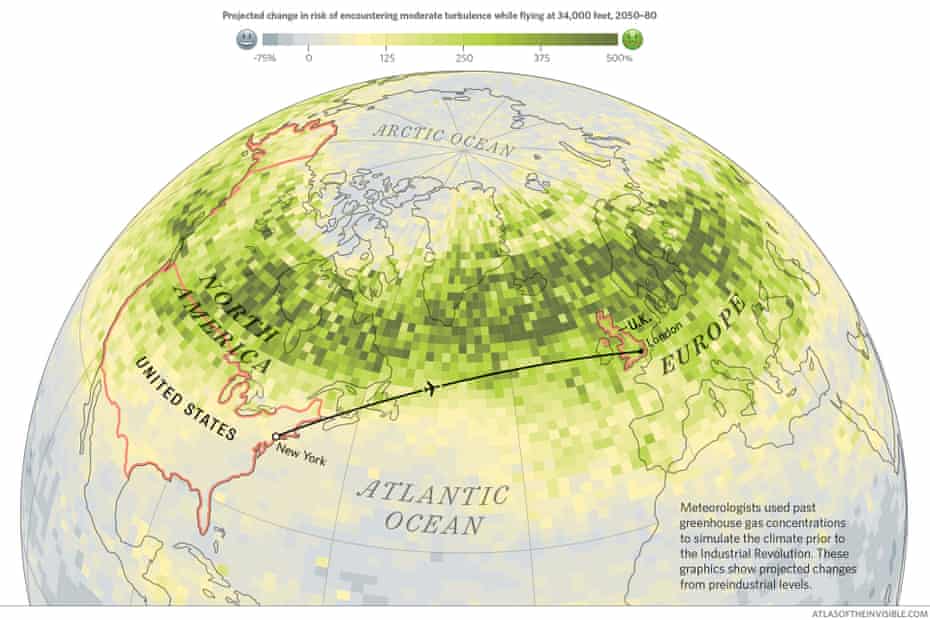

James Cheshire and Oliver Uberti in The Guardian: “In a new book, Atlas of the Invisible, the geographer James Cheshire and designer Oliver Uberti redefine what an atlas can be. The following eight graphics reveal some of the causes and consequences of the climate crisis that are hard to detect with the naked eye but become clear when the data is collected and visualised.

Fasten your seatbelts

The Federal Aviation Administration in the US reported only nine serious injuries from clear-air turbulence out of 1 billion passengers in 2018, but the risk persists because neither captains nor their onboard instruments can see rough air ahead; instead they rely on other pilots and flight dispatchers to warn them. In recent years meteorologists have alerted aviators to bigger bumps coming this century. Simulations show that as the climate crisis makes jet streams more erratic, the chances of encountering turbulent airspace will soar, especially in autumn and winter along the busiest routes. All the more reason to cut back on transatlantic flights….(More)”

Press Release: “To better prepare and protect the world from global disease threats, H.E. German Federal Chancellor Dr Angela Merkel and Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization Director-General, will today inaugurate the new WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence, based in Berlin.

“The world needs to be able to detect new events with pandemic potential and to monitor disease control measures on a real-time basis to create effective pandemic and epidemic risk management,” said Dr Tedros. “This Hub will be key to that effort, leveraging innovations in data science for public health surveillance and response, and creating systems whereby we can share and expand expertise in this area globally.”

The WHO Hub, which is receiving an initial investment of US$ 100 million from the Federal Republic of Germany, will harness broad and diverse partnerships across many professional disciplines, and the latest technology, to link the data, tools and communities of practice so that actionable data and intelligence are shared for the common good.

The WHO Hub is part of WHO’s Health Emergencies Programme and will be a new collaboration of countries and partners worldwide, driving innovations to increase availability of key data; develop state of the art analytic tools and predictive models for risk analysis; and link communities of practice around the world. Critically, the WHO Hub will support the work of public health experts and policy-makers in all countries with the tools needed to forecast, detect and assess epidemic and pandemic risks so they can take rapid decisions to prevent and respond to future public health emergencies.

“Despite decades of investment, COVID-19 has revealed the great gaps that exist in the world’s ability to forecast, detect, assess and respond to outbreaks that threaten people worldwide,” said Dr Michael Ryan, Executive Director of WHO’s Health Emergency Programme. “The WHO Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence is designed to develop the data access, analytic tools and communities of practice to fill these very gaps, promote collaboration and sharing, and protect the world from such crises in the future.”

The Hub will work to:

- Enhance methods for access to multiple data sources vital to generating signals and insights on disease emergence, evolution and impact;

- Develop state of the art tools to process, analyze and model data for detection, assessment and response;

- Provide WHO, our Member States, and partners with these tools to underpin better, faster decisions on how to address outbreak signals and events; and

- Connect and catalyze institutions and networks developing disease outbreak solutions for the present and future.

Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu, currently Director-General of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, has been appointed to lead the WHO Hub….(More)”

Interview by Jill Suttie: “Humans have a long history of cooperating together, which has helped us survive and thrive for hundreds of thousands of years in places around the world. But we don’t always cooperate well, even when doing so could help us overcome a worldwide pandemic or solve our climate crisis. The question is why?

In Nichola Raihani’s new book, The Social Instinct: How Cooperation Shaped the World, we find some answers to this question. Raihani, a professor of evolution and behavior at University College London, provides an in-depth treatise on how cooperation evolved, noting its benefits as well as its downsides in human and non-human social groups. By taking a deeper dive into what it means to cooperate, she hopes to illuminate how cooperation can help us solve collective problems, while encouraging some humility in us along the way.

Greater Good spoke to Raihani about her book. Below is an edited version of our conversation….

JS: Are you optimistic about us being able to cooperate to solve big world problems?

NR: I feel we definitely can; it’s not out of the realm of possibility. But having watched how the response to the pandemic has played out so far emphasizes that it won’t be easy.

If you think about it, there are many features of the pandemic that should make it way easier to effectively cooperate. There’s no ambiguity about it being an active disease; most people would like to avoid catching it. The economic incentives to tackle it are aligned with mitigation strategies, so if we managed to solve the pandemic crisis, the economy would recover. And the pandemic isn’t some future generation’s problem; it’s all of our problem, here and now. So, compared to the climate crisis, a pandemic should be much easier to focus people’s minds on and get them to organize around collective solutions.

And yet our response to the pandemic so far has been rather parochial and piecemeal. Think about the way vaccines have been distributed around the world. We are really interdependent, and we’re not going to get out of the pandemic until we’re all out of the pandemic. But this doesn’t seem to be the thinking of various governments around the world.

So, when you think about climate change, even though it’s increasingly a here-and-now issue, it’s still something we don’t treat as a collective problem. The economic costs of climate action are perceived by many to be greater than the costs of organizing collective action. And, since not all countries will experience the cost of climate change in the same way or to the same extent, there is a disparity of concern around climate change that makes it difficult to tackle it.

Having said all that, I think there is still room for optimism. The pandemic has shown us that the vast majority of people are willing to accept massive constraints on their lifestyle to help produce a collective outcome that we all desire. It has also shown us how quickly some of the tipping points in behavior can be achieved, when the situation demands it. Over the course of six months, a vast proportion of the country’s workforce has transitioned to remote working—a behavioral shift that, under normal circumstances, might have taken a decade.

We now need to find those similar tipping points in our response to the climate crisis, and we are starting to see signs that they might appear. To give just one example, the proportion of renewable energy that was cheaper than fossil fuels doubled in 2020, and 62% of renewable energy options were cheaper than fossil fuels. This aligning of economic and ecological incentives helps to reveal the path we might take to tackling the climate crisis. And, although it sounds a little perverse, the fact that rich Western countries are increasingly experiencing the negative impacts of climate change themselves might also help to focus the minds of leaders to take action….(More)”.

Blog by Edmund L. Andrews: “In a move to democratize research on artificial intelligence and medicine, Stanford’s Center for Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Imaging (AIMI) is dramatically expanding what is already the world’s largest free repository of AI-ready annotated medical imaging datasets.

Artificial intelligence has become an increasingly pervasive tool for interpreting medical images, from detecting tumors in mammograms and brain scans to analyzing ultrasound videos of a person’s pumping heart.

Many AI-powered devices now rival the accuracy of human doctors. Beyond simply spotting a likely tumor or bone fracture, some systems predict the course of a patient’s illness and make recommendations.

But AI tools have to be trained on expensive datasets of images that have been meticulously annotated by human experts. Because those datasets can cost millions of dollars to acquire or create, much of the research is being funded by big corporations that don’t necessarily share their data with the public.

“What drives this technology, whether you’re a surgeon or an obstetrician, is data,” says Matthew Lungren, co-director of AIMI and an assistant professor of radiology at Stanford. “We want to double down on the idea that medical data is a public good, and that it should be open to the talents of researchers anywhere in the world.”

Launched two years ago, AIMI has already acquired annotated datasets for more than 1 million images, many of them from the Stanford University Medical Center. Researchers can download those datasets at no cost and use them to train AI models that recommend certain kinds of action.

Now, AIMI has teamed up with Microsoft’s AI for Health program to launch a new platform that will be more automated, accessible, and visible. It will be capable of hosting and organizing scores of additional images from institutions around the world. Part of the idea is to create an open and global repository. The platform will also provide a hub for sharing research, making it easier to refine different models and identify differences between population groups. The platform can even offer cloud-based computing power so researchers don’t have to worry about building local resource intensive clinical machine-learning infrastructure….(More)”.

Paper by Clodagh Harris: “The effects of climate change are multiple and fundamental. Decisions made today may result in irreversible damage to the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems, the detrimental impacts of which will be borne by today’s children, young people and those yet unborn (future generations). The use of citizens’ assemblies (CAs) to tackle the issue of climate change is growing. Their remit is future focused. Yet is the future in the room? Focusing on a single case study, the recent Irish CA and Joint Oireachtas Committee on Climate Action (JOCCA) deliberations on climate action, this paper explores the extent to which children, young people and future generations were included. Its systemic analysis of the membership of both institutions, the public submissions to them and the invited expertise presented, finds that the Irish CA was ‘too tightly coupled’ on this issue. This may have been beneficial in terms of impact, but it came at the expense of input legitimacy and potentially intergenerational justice. Referring to international developments, it suggests how these groups may be included through enclave deliberation, institutional innovations, design experiments and future-oriented practice…(More)”

Paper by Adam J. Andreotta, Nin Kirkham & Marco Rizzi: “In this paper, we discuss several problems with current Big data practices which, we claim, seriously erode the role of informed consent as it pertains to the use of personal information. To illustrate these problems, we consider how the notion of informed consent has been understood and operationalised in the ethical regulation of biomedical research (and medical practices, more broadly) and compare this with current Big data practices. We do so by first discussing three types of problems that can impede informed consent with respect to Big data use. First, we discuss the transparency (or explanation) problem. Second, we discuss the re-repurposed data problem. Third, we discuss the meaningful alternatives problem. In the final section of the paper, we suggest some solutions to these problems. In particular, we propose that the use of personal data for commercial and administrative objectives could be subject to a ‘soft governance’ ethical regulation, akin to the way that all projects involving human participants (e.g., social science projects, human medical data and tissue use) are regulated in Australia through the Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs). We also consider alternatives to the standard consent forms, and privacy policies, that could make use of some of the latest research focussed on the usability of pictorial legal contracts…(More)”

Apoorva Mandavilli at the New York Times: “When the coronavirus surfaced last year, no one was prepared for it to invade every aspect of daily life for so long, so insidiously. The pandemic has forced Americans to wrestle with life-or-death choices every day of the past 18 months — and there’s no end in sight.

Scientific understanding of the virus changes by the hour, it seems. The virus spreads only by close contact or on contaminated surfaces, then turns out to be airborne. The virus mutates slowly, but then emerges in a series of dangerous new forms. Americans don’t need to wear masks. Wait, they do.

At no point in this ordeal has the ground beneath our feet seemed so uncertain. In just the past week, federal health officials said they would begin offering booster shots to all Americans in the coming months. Days earlier, those officials had assured the public that the vaccines were holding strong against the Delta variant of the virus, and that boosters would not be necessary.

As early as Monday, the Food and Drug Administration is expected to formally approve the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, which has already been given to scores of millions of Americans. Some holdouts found it suspicious that the vaccine was not formally approved yet somehow widely dispensed. For them, “emergency authorization” has never seemed quite enough.

Americans are living with science as it unfolds in real time. The process has always been fluid, unpredictable. But rarely has it moved at this speed, leaving citizens to confront research findings as soon as they land at the front door, a stream of deliveries that no one ordered and no one wants.

Is a visit to my ailing parent too dangerous? Do the benefits of in-person schooling outweigh the possibility of physical harm to my child? Will our family gathering turn into a superspreader event?

Living with a capricious enemy has been unsettling even for researchers, public health officials and journalists who are used to the mutable nature of science. They, too, have frequently agonized over the best way to keep themselves and their loved ones safe.

But to frustrated Americans unfamiliar with the circuitous and often contentious path to scientific discovery, public health officials have seemed at times to be moving the goal posts and flip-flopping, or misleading, even lying to, the country.

Most of the time, scientists are “edging forward in a very incremental way,” said Richard Sever, assistant director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press and a co-founder of two popular websites, bioRxiv and medRxiv, where scientists post new research.

“There are blind alleys that people go down, and a lot of the time you kind of don’t know what you don’t know.”

Biology and medicine are particularly demanding fields. Ideas are evaluated for years, sometimes decades, before they are accepted….(More)”.

Sara Frueh at the National Academies: “Even among those who share the same faith or ethnic background, small differences in rituals can seem insurmountable, added Legare, relaying the example of a friend’s deep disagreement with her new husband over whether presents should be opened on Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. “There was a lot of family strife surrounding something that seems pretty trivial.”

Why do these small differences matter so much? Rituals help support group identity and preserve communities over time – which means they aren’t easily altered, said Legare. “Resisting change is part of the structural fabric of ritual.”

Reshaping Rituals Big and Small

If rituals are built to resist change, what happens when massive change — like a pandemic — is forced upon them?

We responded not by scrapping our rituals but by modifying them, which attests to their importance, said Legare. “The functions that these rituals serve are still things that humans need, that we crave.” For example, rites of passage — birthday parties, baby showers, funerals — have moved online. “We still need these critical life events to be commemorated, to be respected.”

One reason the pandemic has been uniquely difficult is that it’s a normal reaction to gather together in times of uncertainty and hardship — something made difficult or impossible by the social distancing needed to slow the spread of disease, said Legare. “It explains why rather than just omitting a lot of these rituals, we have changed and transformed them.”

Rituals are particularly helpful in situations of uncertainty or danger; they can help us reestablish a feeling of control, explained Legare, and theories hold that rituals support our physiological and psychological drive to reach homeostasis — a feeling of stability and balance. Reading or praying together in collective settings, for example, can have powerful psychological effects in reducing anxiety. “It’s a big part of why we find engaging in synchronous, collective activity so soothing,” she said.

In addition, Legare noted, anthropologists believe that rituals may be part of a hazard-precaution system — a psychological system geared toward responding to threats in the environment, such as pathogens and contamination. “Since reducing contamination and promoting hygiene is essential to human health and survival, using rituals to spread these practices is really useful,” she said. “So it’s absolutely not a surprise that we ritualize hand-washing.” This is nothing new, she added; for very functional reasons, hygiene is part of both secular and religious rituals around the world…(More)”.