Stefaan Verhulst

Paper by Pietro Foini, Michele Tizzoni, Daniela Paolotti, and Elisa Omodei: “Food insecurity, defined as the lack of physical or economic access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food, remains one of the main challenges included in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Near real-time data on the food insecurity situation collected by international organizations such as the World Food Programme can be crucial to monitor and forecast time trends of insufficient food consumption levels in countries at risk.

Here, using food consumption observations in combination with secondary data on conflict, extreme weather events and economic shocks, we build a forecasting model based on gradient boosted regression trees to create predictions on the evolution of insufficient food consumption trends up to 30 days in to the future in 6 countries (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali, Nigeria, Syria and Yemen). Results show that the number of available historical observations is a key element for the forecasting model performance. Among the 6 countries studied in this work, for those with the longest food insecurity time series, the proposed forecasting model makes it possible to forecast the prevalence of people with insufficient food consumption up to 30 days into the future with higher accuracy than a naive approach based on the last measured prevalence only. The framework developed in this work could provide decision makers with a tool to assess how the food insecurity situation will evolve in the near future in countries at risk. Results clearly point to the added value of continuous near real-time data collection at sub-national level…(More)”.

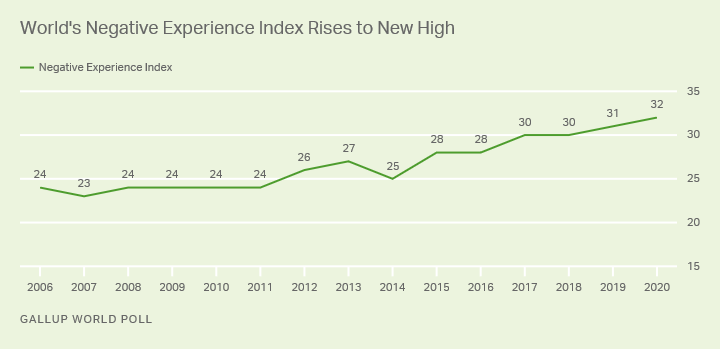

Gallup: “Nobody was alone in feeling more sad, angry, worried or stressed last year. Gallup’s latest Negative Experience Index, which annually tracks these experiences worldwide in more than 100 countries and areas, shows that collectively, the world was feeling the worst it had in 15 years. The index score reached a new high of 32 in 2020.

Line graph. The Negative Experience Index, an annual composite index of stress, anger, worry, sadness and physical pain, continued to rise in 2020, hitting a new record of 32.

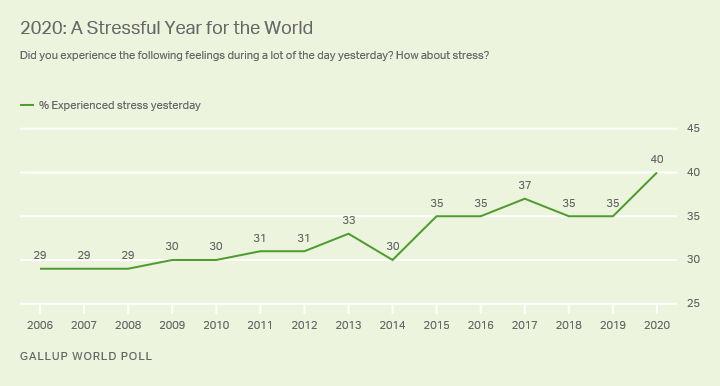

Gallup asked adults in 115 countries and areas if they had five specific negative experiences on the day preceding the survey. Four in 10 adults said they had experienced worry (40%) or stress (40%), and just under three in 10 had experienced physical pain (29%) during a lot of the previous day. About one in four or more experienced sadness (27%) or anger (24%).

Already at or near record highs in 2019, experiences of worry, stress, sadness and anger continued to gain steam and set new records in 2020. Worry and sadness each rose one percentage point, anger rose two, and stress rocketed up five. The percentage of adults worldwide who experienced pain was the only index item that declined — dropping two points after holding steady for several years at 31%.

But 2020 officially became the most stressful year in recent history. The five-point jump from 35% in 2019 to 40% in 2020 represents nearly 190 million more people globally who experienced stress during a lot of the previous day.

Line graph. Reported stress worldwide soared to a record 40% in 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Worldwide, not everyone was feeling this stress to the same degree. Reported stress ranged from a high of 66% in Peru — which represents a new high for the country — to a low of 13% in Kyrgyzstan, where stress levels have historically been low and stayed low in 2020….(More)”

Blogpost by Ganna Pogrebna: “Behavioral Data Science is a new, emerging, interdisciplinary field, which combines techniques from the behavioral sciences, such as psychology, economics, sociology, and business, with computational approaches from computer science, statistics, data-centric engineering, information systems research and mathematics, all in order to better model, understand and predict behavior.

Behavioral Data Science lies at the interface of all these disciplines (and a growing list of others) — all interested in combining deep knowledge about the questions underlying human, algorithmic, and systems behavior with increasing quantities of data. The kinds of questions this field engages are not only exciting and challenging, but also timely, such as:

- How can people’s wellbeing at scale be measured and improved using behavioral data science?

- How can we improve the entire supply chain in creative industries and produce movies, which viewers really want to see?

- How can we better understand machine behavior and algorithmic behavior?

- How can we better model social systems by mapping risk through time?

- How can we design and deliver personalized services ethically and responsibly?

Behavioral Data Science is capable of addressing all these issues (and many more) partly because of the availability of new data sources and partly due to the emergence of new (hybrid) models, which merge behavioral science and data science models. The main advantage of these models is that they expand machine learning techniques, operating, essentially, as black boxes, to fully tractable, and explainable upgrades. Specifically, while a deep learning model can generate accurate prediction of why people select one product or brand over the other, it will not tell you what exactly drives people’s preferences; whereas hybrid models, such as anthropomorphic learning, will be able to provide this insight….(More)”

Roxane Gay at the New York Times: “When I joined Twitter 14 years ago, I was living in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, attending graduate school. I lived in a town of around 4,000 people, with few Black people or other people of color, not many queer people and not many writers. Online is where I found a community beyond my graduate school peers. I followed and met other emerging writers, many of whom remain my truest friends. I got to share opinions, join in on memes, celebrate people’s personal joys, process the news with others and partake in the collective effervescence of watching awards shows with thousands of strangers.

Something fundamental has changed since then. I don’t enjoy most social media anymore. I’ve felt this way for a while, but I’m loath to admit it.

Increasingly, I’ve felt that online engagement is fueled by the hopelessness many people feel when we consider the state of the world and the challenges we deal with in our day-to-day lives. Online spaces offer the hopeful fiction of a tangible cause and effect — an injustice answered by an immediate consequence. On Twitter, we can wield a small measure of power, avenge wrongs, punish villains, exalt the pure of heart….

Lately, I’ve been thinking that what drives so much of the anger and antagonism online is our helplessness offline. Online we want to be good, to do good, but despite these lofty moral aspirations, there is little generosity or patience, let alone human kindness. There is a desperate yearning for emotional safety. There is a desperate hope that if we all become perfect enough and demand the same perfection from others, there will be no more harm or suffering.

It is infuriating. It is also entirely understandable. Some days, as I am reading the news, I feel as if I am drowning. I think most of us do. At least online, we can use our voices and know they can be heard by someone.

It’s no wonder that we seek control and justice online. It’s no wonder that the tenor of online engagement has devolved so precipitously. It’s no wonder that some of us have grown weary of it….(More)”

Paper by Armin Falk: “We document individual willingness to fight climate change and its behavioral determinants in a large representative sample of US adults. Willingness to fight climate change – as measured through an incentivized donation decision – is highly heterogeneous across the population. Individual beliefs about social norms, economic preferences such as patience and altruism, as well as universal moral values positively predict climate preferences. Moreover, we document systematic misperceptions of prevalent social norms. Respondents vastly underestimate the prevalence of climate- friendly behaviors and norms among their fellow citizens. Providing respondents with correct information causally raises individual willingness to fight climate change as well as individual support for climate policies. The effects are strongest for individuals who are skeptical about the existence and threat of global warming…(More)”.

Press Release: “Americans have always disagreed about politics, but now levels of anti-democratic attitudes, support for partisan violence, and partisan animosity have reached concerning levels. While there are many ideas for tackling these problems, they have never been gathered, tested, and evaluated in a unified effort. To address this gap, the Stanford Polarization and Social Change Lab is launching a major new initiative. The Strengthening Democracy Challenge will collect and rigorously test up to 25 interventions to reduce anti-democratic attitudes, support for partisan violence, and partisan animosity in one massive online experiment with up to 30,000 participants. Interventions can be contributed by academics, practitioners, or others with interest in strengthening democratic principles in the US. The researchers who organize the challenge — a multidisciplinary team with members at Stanford, MIT, Northwestern, and Columbia Universities — believe that crowdsourcing ideas, combined with the rigor of large-scale experimentation, can help address issues as substantial and complex as these….

Researchers with diverse backgrounds and perspectives are invited to submit interventions. The proposed interventions must be short, doable in an online form, and follow the ethical guidelines of the challenge. Academic and practitioner experts will rate the submissions and an editorial board will narrow down the 25 best submissions to be tested, taking novelty and expected success of the ideas into account. Co-organizers of the challenge include James Druckman, Payson S. Wild Professor of Political Science at Northwestern University; David Rand, the Erwin H. Schell Professor and Professor of Management Science and Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT; James Chu, Assistant Professor of Sociology at Columbia University; and Nick Stagnaro, Post-Doctoral Fellow at MIT. The organizing team is supported by Polarization and Social Change Lab’s Chrystal Redekopp, Joe Mernyk, and Sophia Pink.

The study participants will be a large sample of up to 30,000 self-identified Republicans and Democrats, nationally representative on several major demographic benchmarks….(More)”.

Mark Dunbar at the Hedgehog Review: “Identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are the beginning and the end of the self. They are how we define ourselves and how we are defined by others. One is a “nerd” or a “jock” or a “know-it-all.” One is “liberal” or “conservative,” “religious” or “secular,” “white” or “black.” Identities are the means of escape and the ties that bind. They direct our thoughts. They are modes of being. They are an ingredient of the self—along with relationships, memories, and role models—and they can also destroy the self. Consume it. The Jungians are right when they say people don’t have identities, identities have people. And the Lacanians are righter still when they say that our very selves—our wishes, desires, thoughts—are constituted by other people’s wishes, desires, and thoughts. Yes, identities are dangerous and paradoxical things. They are expressions of inner selves, and a way the outside gets in.

Our contemporary politics is diseased—that much is widely acknowledged—and the problem of identity is often implicated in its pathology, mostly for the wrong reasons. When it comes to its role in our politics, identity is the chief means by which we substitute behavior for action, disposition for conviction. Everything is rendered political—from the cars we drive to the beer we drink—and this rendering lays bare a political order lacking in democratic vitality. There is an inverse relationship between the rise of identity signaling and the decline of democracy. The less power people have to influence political outcomes, the more emphasis they will put on signifying their political desires. The less politics effects change, the more politics will affect mood.

Dozens of books (and hundreds of articles and essays) have been written about the rising threat of tribalism and group thinking, identity politics, and the politics of resentment….(More)”.

Abel Wajnerman Paz at Rest of the World: “Neurotechnology” is an umbrella term for any technology that can read and transcribe mental states by decoding and modulating neural activity. This includes technologies like closed-loop deep brain stimulation that can both detect neural activity related to people’s moods and can suppress undesirable symptoms, like depression, through electrical stimulation.

Despite their evident usefulness in education, entertainment, work, and the military, neurotechnologies are largely unregulated. Now, as Chile redrafts its constitution — disassociating it from the Pinochet surveillance regime — legislators are using the opportunity to address the need for closer protection of people’s rights from the unknown threats posed by neurotechnology.

Although the technology is new, the challenge isn’t. Decades ago, similar international legislation was passed following the development of genetic technologies that made possible the collection and application of genetic data and the manipulation of the human genome. These included the Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights in 1997 and the International Declaration on Human Genetic Data in 2003. The difference is that, this time, Chile is a leading light in the drafting of neuro-rights legislation.

In Chile, two bills — a constitutional reform bill, which is awaiting approval by the Chamber of Deputies, and a bill on neuro-protection — will establish neuro-rights for Chileans. These include the rights to personal identity, free will, mental privacy, equal access to cognitive enhancement technologies, and protection against algorithmic bias….(More)”.

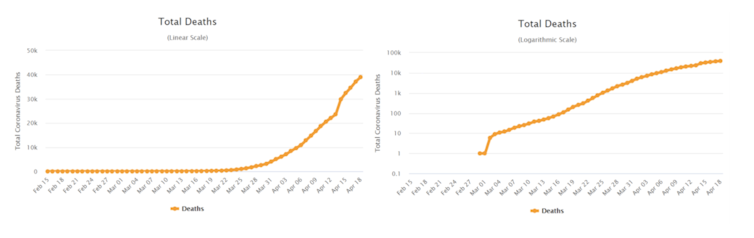

Manuel León Urrutia at The Conversation: “I find it tempting to celebrate the public’s expanding access to data and familiarity with terms like “flattening the curve”. After all, a better informed society is a successful society, and the provision of data-driven information to the public seems to contribute to the notion that together we can beat COVID.

But increased data visibility shouldn’t necessarily be interpreted as increased data literacy. For example, at the start of the pandemic it was found that the portrayal of COVID deaths in logarithmic graphs confused the public. Logarithmic graphs control for data that’s growing exponentially by using a scale which increases by a factor of ten on the y, or vertical axis. This led some people to radically underestimate the dramatic rise in COVID cases.

The vast amount of data we now have available doesn’t even guarantee consensus. In fact, instead of solving the problem, this data deluge can contribute to the polarisation of public discourse. One study recently found that COVID sceptics use orthodox data presentation techniques to spread their controversial views, revealing how more data doesn’t necessarily result in better understanding. Though data is supposed to be objective and empirical, it has assumed a political, subjective hue during the pandemic….

This is where educators come in. The pandemic has only strengthened the case presented by academics for data literacy to be included in the curriculum at all educational levels, including primary. This could help citizens navigate our data-driven world, protecting them from harmful misinformation and journalistic malpractice.

Data literacy does in fact already feature in many higher education roadmaps in the UK, though I’d argue it’s a skill the entire population should be equipped with from an early age. Misconceptions about vaccine efficacy and the severity of the coronavirus are often based on poorly presented, false or misinterpreted data. The “fake news” these misconceptions generate would spread less ferociously in a world of data literate citizens.

To tackle misinformation derived from the current data deluge, the European Commission has funded projects such as MediaFutures and YourDataStories….(More)”.

Paper by Anushri Gupta and Luca Mora: “The age of big data and smart city technologies provides city governments with unprecedented potential for data-driven decision making. Committed to constantly developing new urban policy and supporting urban operations, city governments have been using data describing the functioning of urban infrastructure assets and public services for a very long time. However, the widespread diffusion of digital systems has now created a remarkable new window of opportunity.

With many digital solutions being introduced into the built environment to improve the sustainability of urban sociotechnical systems, enormous amounts of data are constantly generated at the city level, and at unprecedented speed. City surveillance cameras, government applications for public services, building automation systems, intelligent transport systems, and smart grids are some examples of digital technologies which are contributing to producing an exhaustive stream of data “that can be harnessed to provide urban intelligence and reshape the practices and processes of public administrations”, creating a fertile environment for innovation and entrepreneurial activity. When attempting to tap into these large streams of city data, however, the opportunity to deliver sustainable value is met with significant sociotechnical challenges, which undermine the capability of urban development actors….(More)”.