Stefaan Verhulst

Essay by Erik Angner: “Ignorance,” wrote Charles Darwin in 1871, “more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

Darwin’s insight is worth keeping in mind when dealing with the current coronavirus crisis. That includes those of us who are behavioral scientists. Overconfidence—and a lack of epistemic humility more broadly—can cause real harm.

In the middle of a pandemic, knowledge is in short supply. We don’t know how many people are infected, or how many people will be. We have much to learn about how to treat the people who are sick—and how to help prevent infection in those who aren’t. There’s reasonable disagreement on the best policies to pursue, whether about health care, economics, or supply distribution. Although scientists worldwide are working hard and in concert to address these questions, final answers are some ways away.

Another thing that’s in short supply is the realization of how little we know. Even a quick glance at social or traditional media will reveal many people who express themselves with way more confidence than they should…

Frequent expressions of supreme confidence might seem odd in light of our obvious and inevitable ignorance about a new threat. The thing about overconfidence, though, is that it afflicts most of us much of the time. That’s according to cognitive psychologists, who’ve studied the phenomenon systematically for half a century. Overconfidence has been called “the mother of all psychological biases.” The research has led to findings that are at the same time hilarious and depressing. In one classic study, for example, 93 percent of U.S. drivers claimed to be more skillful than the median—which is not possible.

“But surely,” you might object, “overconfidence is only for amateurs—experts would not behave like this.” Sadly, being an expert in some domain does not protect against overconfidence. Some research suggests that the more knowledgeable are more prone to overconfidence. In a famous study of clinical psychologists and psychology students, researchers asked a series of questions about a real person described in psychological literature. As the participants received more and more information about the case, their confidence in their judgment grew—but the quality of their judgment did not. And psychologists with a Ph.D. did no better than the students….(More)”.

Paper by Mirco Nanni: “The rapid dynamics of COVID-19 calls for quick and effective tracking of virus transmission chains and early detection of outbreaks, especially in the phase 2 of the pandemic, when lockdown and other restriction measures are progressively withdrawn, in order to avoid or minimize contagion resurgence. For this purpose, contact-tracing apps are being proposed for large scale adoption by many countries. A centralized approach, where data sensed by the app are all sent to a nation-wide server, raises concerns about citizens’ privacy and needlessly strong digital surveillance, thus alerting us to the need to minimize personal data collection and avoiding location tracking.

We advocate the conceptual advantage of a decentralized approach, where both contact and location data are collected exclusively in individual citizens’ “personal data stores”, to be shared separately and selectively, voluntarily, only when the citizen has tested positive for COVID-19, and with a privacy preserving level of granularity.

This approach better protects the personal sphere of citizens and affords multiple benefits: it allows for detailed information gathering for infected people in a privacy-preserving fashion; and, in turn this enables both contact tracing, and, the early detection of outbreak hotspots on more finely-granulated geographic scale. Our recommendation is two-fold. First to extend existing decentralized architectures with a light touch, in order to manage the collection of location data locally on the device, and allow the user to share spatio-temporal aggregates – if and when they want, for specific aims – with health authorities, for instance. Second, we favour a longer-term pursuit of realizing a Personal Data Store vision, giving users the opportunity to contribute to collective good in the measure they want, enhancing self-awareness, and cultivating collective efforts for rebuilding society….(More)”

Paper by Cass Sunstein: “Many incentives are monetary, and when private or public institutions seek to change behavior, it is natural to change monetary incentives. But many other incentives are a product of social meanings, about which people may not much deliberate, but which can operate as subsidies or as taxes. In some times and places, for example the social meaning of smoking has been positive, increasing the incentive to smoke; in other times and places, it has been negative, and thus served to reduce smoking.

With respect to safety and health, social meanings change radically over time, and they can be dramatically different in one place from what they are in another. Often people live in accordance with meanings that they deplore, or at least wish were otherwise. But it is exceptionally difficult for individuals to alter meanings on their own. Alteration of meanings can come from law, which may, through a mandate, transform the meaning of action into a bland, “I comply with law,” or into a less bland, “I am a good citizen.” Alteration of social meanings can also come from large-scale private action, engineered or promoted by “meaning entrepreneurs,” who can turn the meaning of action from, “I am an oddball,” to, “I do my civic duty,” or, “I protect others from harm.” Sometimes subgroups rebel against new or altered meanings, produced by law or meaning entrepreneurs, but often those meanings stick and produce significant change….(More)”.

Paper by Victoria Perez and Justin M. Ross: “Networks of overlapping local governments are the front line of governmental responses to pandemics. Local governments, both general purpose (municipalities, counties, etc.) and special districts (school, fire, police, hospital, etc.), implement state and federal directives while acting as a producer and as a third-party payer in the healthcare system. They possess local information necessary in determining the best use of finite resources and available assets. Furthermore, a liberal society requires voluntary cooperation of citizens skeptical of opportunistic authoritarianism. Therefore, successful local governance instills a reassuring division of political power.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created two significant challenges for local governments in their efforts to respond effectively to the crisis: public finance and intergovernmental collaboration. This brief recommends practical solutions to meet these challenges….(More)”.

Essay by Frank D. LoMonte at the Journal of Civic Information: “In an April 1 interview with NPR’s “Morning Edition,” retired U.S. Army Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal, former commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, explained that, in a crisis situation, accurate information from government authorities can be crucial in reassuring the public – and in the absence of accurate information, speculation and rumor will proliferate. Joni Mitchell, who’s probably never before appeared in the same paragraph with Stanley McChrystal, might have put it a touch more poetically: “Don’t it always seem to go; That you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone.”

The outbreak of the coronavirus strain COVID-19, which prompted the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to declare a public health emergency on Jan. 31, 2020,3 is introducing Americans to a newfound world of austerity and loss. Professional haircuts, sit-down restaurant meals and recreational plane flights increasingly seem like memories from a bygone golden age (small inconveniences, to be sure, alongside the suffering of thousands who’ve died and the families they’ve left behind).

Access to information from government agencies, too, is adapting to a mail-order, drive-through society. As public-health authorities reached consensus that the spread of COVID-19 could be contained only by eliminating non-essential travel and group gatherings, strict adherence to open-meeting and public-records laws became a casualty alongside salad bars and theme-park rides. Governors and legislatures relaxed, or entirely waived, compliance with statutes that require agencies to open their meetings to in-person public attendance and promptly fulfill requests for documents.

As with all other areas of public life, some sacrifices in open-government formalities are unavoidable. With agencies down to a sustenance-level crew of essential workers, it’s unrealistic to expect that decades-old paper documents will be speedily located and produced. And it’s unsafe to invite people to congregate at public hearings to address their elected officials. But the public shouldn’t be alone in the sacrifice….(More)”.

Karen Hao at MIT Technology Review: “When it comes to predicting the spread of an infectious disease, it’s crucial to understand what Ryan Tibshirani, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University, calls the “the pyramid of severity.” The bottom of the pyramid is asymptomatic carriers (those who have the infection but feel fine); the next level is symptomatic carriers (those who are feeling ill); then come hospitalizations, critical hospitalizations, and finally deaths.

Every level of the pyramid has a clear relationship to the next: “For example, sadly, it’s pretty predictable how many people will die once you know how many people are under critical care,” says Tibshirani, who is part of CMU’s Delphi research group, one of the best flu-forecasting teams in the US. The goal, therefore, is to have a clear measure of the lower levels of the pyramid, as the foundation for forecasting the higher ones.

But in the US, building such a model is a Herculean task. A lack of testing makes it impossible to assess the number of asymptomatic carriers. The results also don’t accurately reflect how many symptomatic carriers there are. Different counties have different testing requirements—some choosing only to test patients who require hospitalization. Test results also often take upwards of a week to return.

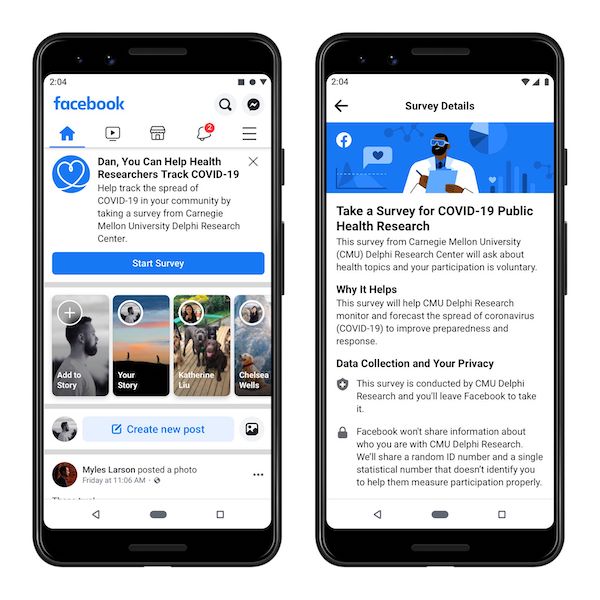

The remaining option is to measure symptomatic carriers through a large-scale, self-reported survey. But such an initiative won’t work unless it covers a big enough cross section of the entire population. Now the Delphi group, which has been working with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to help it coordinate the national pandemic response, has turned to the largest platforms in the US: Facebook and Google.

In a new partnership with Delphi, both tech giants have agreed to help gather data from those who voluntarily choose to report whether they’re experiencing covid-like symptoms. Facebook will target a fraction of their US users with a CMU-run survey, while Google has thus far been using its Opinion Rewards app, which lets users respond to questions for app store credit. The hope is this new information will allow the lab to produce county-by-county projections that will help policymakers allocate resources more effectively.

Neither company will ever actually see the survey results; they’re merely pointing users to the questions administered and processed by the lab. The lab will also never share any of the raw data back to either company. Still, the agreements represent a major deviation from typical data-sharing practices, which could raise privacy concerns. “If this wasn’t a pandemic, I don’t know that companies would want to take the risk of being associated with or asking directly for such a personal piece of information as health,” Tibshirani says.

Without such cooperation, the researchers would’ve been hard pressed to find the data anywhere else. Several other apps allow users to self-report symptoms, including a popular one in the UK known as the Covid Symptom Tracker that has been downloaded over 1.5 million times. But none of them offer the same systematic and expansive coverage as a Facebook or Google-administered survey, says Tibshirani. He hopes the project will collect millions of responses each week….(More)”.

EdgeCast by Toby Ord: “Lately, I’ve been asking myself questions about the future of humanity, not just about the next five years or even the next hundred years, but about everything humanity might be able to achieve in the time to come.

The past of humanity is about 200,000 years. That’s how long Homo sapiens have been around according to our current best guess (it might be a little bit longer). Maybe we should even include some of our other hominid ancestors and think about humanity somewhat more broadly. If we play our cards right, we could live hundreds of thousands of years more. In fact, there’s not much stopping us living millions of years. The typical species lives about a million years. Our 200,000 years so far would put us about in our adolescence, just old enough to be getting ourselves in trouble, but not wise enough to have thought through how we should act.

But a million years isn’t an upper bound for how long we could live. The horseshoe crab, for example, has lived for 450 million years so far. The Earth should remain habitable for at least that long. So, if we can survive as long as the horseshoe crab, we could have a future stretching millions of centuries from now. That’s millions of centuries of human progress, human achievement, and human flourishing. And if we could learn over that time how to reach out a little bit further into the cosmos to get to the planets around other stars, then we could have longer yet. If we went seven light-years at a time just making jumps of that distance, we could reach almost every star in the galaxy by continually spreading out from the new location. There are already plans in progress to send spacecraft these types of distances. If we could do that, the whole galaxy would open up to us….

Humanity is not a typical species. One of the things that most worries me is the way in which our technology might put us at risk. If we look back at the history of humanity these 2000 centuries, we see this initially gradual accumulation of knowledge and power. If you think back to the earliest humans, they weren’t that remarkable compared to the other species around them. An individual human is not that remarkable on the Savanna compared to a cheetah, or lion, or gazelle, but what set us apart was our ability to work together, to cooperate with other humans to form something greater than ourselves. It was teamwork, the ability to work together with those of us in the same tribe that let us expand to dozens of humans working together in cooperation. But much more important than that was our ability to cooperate across time, across the generations. By making small innovations and passing them on to our children, we were able to set a chain in motion wherein generations of people worked across time, slowly building up these innovations and technologies and accumulating power….(More)”.

Nic Fildes and Javier Espinoza at the Financial Times: “When the World Health Organization launched a 2007 initiative to eliminate malaria on Zanzibar, it turned to an unusual source to track the spread of the disease between the island and mainland Africa: mobile phones sold by Tanzania’s telecoms groups including Vodafone, the UK mobile operator.

Working together with researchers at Southampton university, Vodafone began compiling sets of location data from mobile phones in the areas where cases of the disease had been recorded.

Mapping how populations move between locations has proved invaluable in tracking and responding to epidemics. The Zanzibar project has been replicated by academics across the continent to monitor other deadly diseases, including Ebola in west Africa….

With much of Europe at a standstill as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, politicians want the telecoms operators to provide similar data from smartphones. Thierry Breton, the former chief executive of France Telecom who is now the European commissioner for the internal market, has called on operators to hand over aggregated location data to track how the virus is spreading and to identify spots where help is most needed.

Both politicians and the industry insist that the data sets will be “anonymised”, meaning that customers’ individual identities will be scrubbed out. Mr Breton told the Financial Times: “In no way are we going to track individuals. That’s absolutely not the case. We are talking about fully anonymised, aggregated data to anticipate the development of the pandemic.”

But the use of such data to track the virus has triggered fears of growing surveillance, including questions about how the data might be used once the crisis is over and whether such data sets are ever truly anonymous….(More)”.

Book edited by Katharine S. Willis, and Alessandro Aurigi: “The Routledge Companion to Smart Cities explores the question of what it means for a city to be ‘smart’, raises some of the tensions emerging in smart city developments and considers the implications for future ways of inhabiting and understanding the urban condition. The volume draws together a critical and cross-disciplinary overview of the emerging topic of smart cities and explores it from a range of theoretical and empirical viewpoints.

This timely book brings together key thinkers and projects from a wide range of fields and perspectives into one volume to provide a valuable resource that would enable the reader to take their own critical position within the topic. To situate the topic of the smart city for the reader and establish key concepts, the volume sets out the various interpretations and aspects of what constitutes and defines smart cities. It investigates and considers the range of factors that shape the characteristics of smart cities and draws together different disciplinary perspectives. The consideration of what shapes the smart city is explored through discussing three broad ‘parts’ – issues of governance, the nature of urban development and how visions are realised – and includes chapters that draw on empirical studies to frame the discussion with an understanding not just of the nature of the smart city but also how it is studied, understood and reflected upon.

The Companion will appeal to academics and advanced undergraduates and postgraduates from across many disciplines including Urban Studies, Geography, Urban Planning, Sociology and Architecture, by providing state of the art reviews of key themes by leading scholars in the field, arranged under clearly themed sections….(More)”.

Paper by Jouni T. Tuomisto, Mikko V. Pohjola & Teemu J. Rintala: “Evidence-informed decision-making and better use of scientific information in societal decisions has been an area of development for decades but is still topical. Decision support work can be viewed from the perspective of information collection, synthesis and flow between decision-makers, experts and stakeholders. Open policy practice is a coherent set of methods for such work. It has been developed and utilised mostly in Finnish and European contexts.

The evaluation revealed that methods and online tools work as expected, as demonstrated by the assessments and policy support processes conducted. The approach improves the availability of information and especially of relevant details. Experts are ambivalent about the acceptability of openness – it is an important scientific principle, but it goes against many current research and decision-making practices. However, co-creation and openness are megatrends that are changing science, decision-making and the society at large. Against many experts’ fears, open participation has not caused problems in performing high-quality assessments. On the contrary, a key challenge is to motivate and help more experts, decision-makers and citizens to participate and share their views. Many methods within open policy practice have also been widely used in other contexts.

Open policy practice proved to be a useful and coherent set of methods. It guided policy processes toward a more collaborative approach, whose purpose was wider understanding rather than winning a debate. There is potential for merging open policy practice with other open science and open decision process tools. Active facilitation, community building and improving the user-friendliness of the tools were identified as key solutions for improving the usability of the method in the future….(More)”.