Stefaan Verhulst

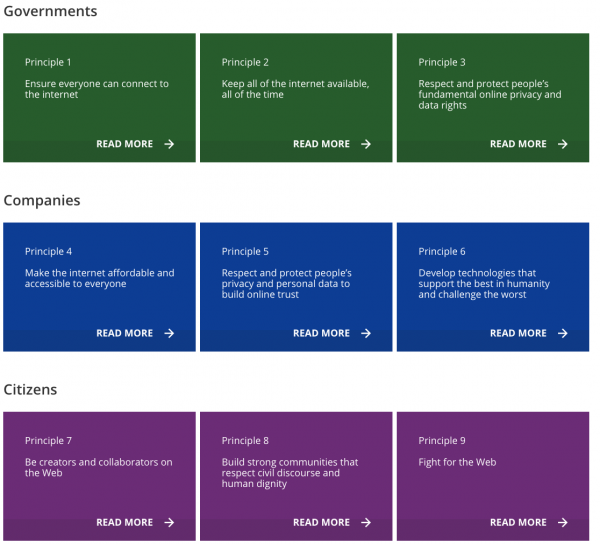

About: “The Web was designed to bring people together and make knowledge freely available. It has changed the world for good and improved the lives of billions. Yet, many people are still unable to access its benefits and, for others, the Web comes with too many unacceptable costs.

Everyone has a role to play in safeguarding the future of the Web. The Contract for the Web was created by representatives from over 80 organizations, representing governments, companies and civil society, and sets out commitments to guide digital policy agendas. To achieve the Contract’s goals, governments, companies, civil society and individuals must commit to sustained policy development, advocacy, and implementation of the Contract’s text…(More)”.

Paper by Quinton Mayne, Jorrit De Jong, and Fernando Fernandez-Monge: “Governments around the world are increasingly recognizing the power of problem-oriented governance as a way to address complex public problems. As an approach to policy design and implementation, problem-oriented governance radically emphasizes the need for organizations to continuously learn and adapt. Scholars of public management, public administration, policy studies, international development, and political science have made important contributions to this problem-orientation turn; however, little systematic attention has been paid to the question of the state capabilities that underpin problem-oriented governance. In this article, we address this gap in the literature.

We argue that three core capabilities are structurally conducive to problem-oriented governance: a reflective-improvement capability, a collaborative capability, and a data-analytic capability. The article presents a conceptual framework for understanding each of these capabilities, including their chief constituent elements. It ends with a discussion of how the framework can advance empirical research as well as public-sector reform….(More)”.

Blogpost by Yasodara Cordova and Eduardo Vicente Goncalvese: “Every month in Brazil, the government team in charge of processing reimbursement expenses incurred by congresspeople receives more than 20,000 claims. This is a manually intensive process that is prone to error and susceptible to corruption. Under Brazilian law, this information is available to the public, making it possible to check the accuracy of this data with further scrutiny. But it’s hard to sift through so many transactions. Fortunately, Rosie, a robot built to analyze the expenses of the country’s congress members, is helping out.

Rosie was born from Operação Serenata de Amor, a flagship project we helped create with other civic hackers. We suspected that data provided by members of Congress, especially regarding work-related reimbursements, might not always be accurate. There were clear, straightforward reimbursement regulations, but we wondered how easily individuals could maneuver around them.

Furthermore, we believed that transparency portals and the public data weren’t realizing their full potential for accountability. Citizens struggled to understand public sector jargon and make sense of the extensive volume of data. We thought data science could help make better sense of the open data provided by the Brazilian government.

Using agile methods, specifically Domain Driven Design, a flexible and adaptive process framework for solving complex problems, our group started studying the regulations, and converting them into software code. We did this by reverse-engineering the legal documents–understanding the reimbursement rules and brainstorming ways to circumvent them. Next, we thought about the traces this circumvention would leave in the databases and developed a way to identify these traces using the existing data. The public expenses database included the images of the receipts used to claim reimbursements and we could see evidence of expenses, such as alcohol, which weren’t allowed to be paid with public money. We named our creation, Rosie.

This method of researching the regulations to then translate them into software in an agile way is called Domain-Driven Design. Used for complex systems, this useful approach analyzes the data and the sector as an ecosystem, and then uses observations and rapid prototyping to generate and test an evolving model. This is how Rosie works. Rosie sifts through the reported data and flags specific expenses made by representatives as “suspicious.” An example could be purchases that indicate the Congress member was in two locations on the same day and time.

After finding a suspicious transaction, Rosie then automatically tweets the results to both citizens and congress members. She invites citizens to corroborate or dismiss the suspicions, while also inviting congress members to justify themselves.

Rosie isn’t working alone. Beyond translating the law into computer code, the group also created new interfaces to help citizens check up on Rosie’s suspicions. The same information that was spread in different places in official government websites was put together in a more intuitive, indexed and machine-readable platform. This platform is called Jarbas – its name was inspired by the AI system that controls Tony Stark’s mansion in Iron Man, J.A.R.V.I.S. (which has origins in the human “Jarbas”) – and it is a website and API (application programming interface) that helps citizens more easily navigate and browse data from different sources. Together, Rosie and Jarbas helps citizens use and interpret the data to decide whether there was a misuse of public funds. So far, Rosie has tweeted 967 times. She is particularly good at detecting overpriced meals. According to an open research, made by the group, since her introduction, members of Congress have reduced spending on meals by about ten percent….(More)”.

Editorial by Howard Bauchner in JAMA: “The goal of making science more transparent—sharing data, posting results on trial registries, use of preprint servers, and open access publishing—may enhance scientific discovery and improve individual and population health, but it also comes with substantial challenges in an era of politicized science, enhanced skepticism, and the ubiquitous world of social media. The recent announcement by the Trump administration of plans to proceed with an updated version of the proposed rule “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science,” stipulating that all underlying data from studies that underpin public health regulations from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must be made publicly available so that those data can be independently validated, epitomizes some of these challenges. According to EPA Administrator Andrew Wheeler: “Good science is science that can be replicated and independently validated, science that can hold up to scrutiny. That is why we’re moving forward to ensure that the science supporting agency decisions is transparent and available for evaluation by the public and stakeholders.”

Virtually every time JAMA publishes an article on the effects of pollution or climate change on health, the journal immediately receives demands from critics to retract the article for various reasons. Some individuals and groups simply do not believe that pollution or climate change affects human health. Research on climate change, and the effects of climate change on the health of the planet and human beings, if made available to anyone for reanalysis could be manipulated to find a different outcome than initially reported. In an age of skepticism about many issues, including science, with the ability to use social media to disseminate unfounded and at times potentially harmful ideas, it is challenging to balance the potential benefits of sharing data with the harms that could be done by reanalysis.

Can the experience of sharing data derived from randomized clinical trials (RCTs)—either as mandated by some funders and journals or as supported by individual investigators—serve as examples as a way to safeguard “truth” in science….

Although the sharing of data may have numerous benefits, it also comes with substantial challenges particularly in highly contentious and politicized areas, such as the effects of climate change and pollution on health, in which the public dialogue appears to be based on as much fiction as fact. The sharing of data, whether mandated by funders, including foundations and government, or volunteered by scientists who believe in the principle of data transparency, is a complicated issue in the evolving world of science, analysis, skepticism, and communication. Above all, the scientific process—including original research and reanalysis of shared data—must prevail, and the inherent search for evidence, facts, and truth must not be compromised by special interests, coercive influences, or politicized perspectives. There are no simple answers, just words of caution and concern….(More)”.

About: “What do companies know about you? How do they handle your data? And who do they share it with?

Access My Info (AMI) is a project that can help answer these questions by assisting you in making data access requests to companies. AMI includes a web application that helps users send companies data access requests, and a research methodology designed to understand the responses companies make to these requests. Past AMI projects have shed light on how companies treat user data and contribute to digital privacy reforms around the world.

What are data access requests?

A data access request is a letter you can send to any company with products/services that you use. The request asks that the company disclose all the information it has about you and whether or not it has shared your data with any third-parties. If the place where you live has data protection laws that include the right to data access then companies may be legally obligated to respond…

AMI has made personal data requests in jurisdictions around the world and found common patterns.

- There are significant gaps between data access laws on paper and the law in practice;

- People have consistently encountered barriers to accessing their data.

Together with our partners in each jurisdiction, we have used Access My Info to set off a dialog between users, civil society, regulators, and companies…(More)”

Essay by Claudia Chwalisz: “….Deliberative bodies such as citizens’ councils, assemblies, and juries are often called “deliberative mini-publics” in academic literature. They are just one aspect of deliberative democracy and involve randomly selected citizens spending a significant period of time developing informed recommendations for public authorities. Many scholars emphasize two core defining features: deliberation (careful and open discussion to weigh the evidence about an issue) and representativeness, achieved through sortition (random selection).

Of course, the principles of deliberation and sortition are not new. Rooted in ancient Athenian democracy, they were used throughout various points of history until around two to three centuries ago. Evoked by the Greek statesman Pericles in 431 BCE, the ideas—that “ordinary citizens, though occupied with the pursuits of industry, are still fair judges of public matters” and that instead of being a “stumbling block in the way of action . . . [discussion] is an indispensable preliminary to any wise action at all”—faded to the background when elections came to dominate the contemporary notion of democracy.

But the belief in the ability of ordinary citizens to deliberate and participate in public decisionmaking has come back into vogue over the past several decades. And it is modern applications of the principles of sortition and deliberation, meaning their adaption in the context of liberal representative democratic institutions, that make them “democratic innovations” today. This is not to say that there are no longer proponents who claim that governance should be the domain of “experts” who are committed to govern for the general good and have superior knowledge to do it. Originally espoused by Plato, the argument in favor of epistocracy—rule by experts—continues to be reiterated, such as in Jason Brennan’s 2016 book Against Democracy. It is a reminder that the battle of ideas for democracy’s future is nothing new and requires constant engagement.

Today’s political context—characterized by political polarization; mistrust in politicians, governments, and fellow citizens; voter apathy; increasing political protests; and a new context of misinformation and disinformation—has prompted politicians, policymakers, civil society organizations, and citizens to reflect on how collective public decisions are being made in the twenty-first century. In particular, political tensions have raised the need for new ways of achieving consensus and taking action on issues that require long-term solutions, such as climate change and technology use. Assembling ordinary citizens from all parts of society to deliberate on a complex political issue has thus become even more appealing.

Some discussions have returned to exploring democracy’s deliberative roots. An ongoing study by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is analyzing over 700 cases of deliberative mini-publics commissioned by public authorities to inform their decisionmaking. The forthcoming report assesses the mini-publics’ use, principles of good practice, and routes to institutionalization.3 This new area of work stems from the 2017 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Open Government, which recommends that adherents (OECD members and some nonmembers) grant all stakeholders, including citizens, “equal and fair opportunities to be informed and consulted and actively engage them in all phases of the policy-cycle” and “promote innovative ways to effectively engage with stakeholders to source ideas and co-create solutions.” A better understanding of how public authorities have been using deliberative mini-publics to inform their decisionmaking around the world, not just in OECD countries, should provide a richer understanding of what works and what does not. It should also reveal the design principles needed for mini-publics to effectively function, deliver strong recommendations, increase legitimacy of the decisionmaking process, and possibly even improve public trust….(More)”.

John Thornhill at the Financial Times: “European politicians who have been complaining recently about the loss of “digital sovereignty” to US technology companies are like children grumbling in the back of a car about where they are heading. …

Sovereign governments used to wield exclusive power over validating identity, running critical infrastructure, regulating information flows and creating money. Several of those functions are being usurped by the latest tech.

Emmanuel Macron, France’s president, recently told The Economist that Europe had inadvertently abandoned the “grammar” of sovereignty by allowing private companies, rather than public interest, to decide on digital infrastructure. In 10 years’ time, he feared, Europe would no longer be able to guarantee the soundness of its cyber infrastructure or control its citizens’ and companies’ data.

The instinctive response of many European politicians is to invest in grand, state-led projects and to regulate the life out of Big Tech. A recent proposal to launch a European cloud computing company, called Gaia-X, reflects the same impulse that lay behind the creation of Quaero, the Franco-German search engine set up in 2008 to challenge Google. That you have to Google “Quaero” rather than Quaero “Quaero” tells you how that fared. The risk of ill-designed regulation is that it can stifle innovation and strengthen the grip of dominant companies.

Rather than just trying to shore up the diminishing sovereignty of European governments and prop up obsolete national industrial champions, leaders may do better to reshape the rules of the data economy to empower users and stimulate a new wave of innovation. True sovereignty, after all, lies in the hands of the people. To this end, Europe should encourage greater efforts to “re-decentralise the web”, as computer scientists say, to accelerate the development of the next generation internet. The principle of privacy by design should be enshrined in the next batch of regulations, following the EU’s landmark General Data Protection Regulation, and written into all public procurement contracts. …(More).

Blogpost by Elizabeth Boomer: “Blockchain, a technology regularly associated with digital currency, is increasingly being utilized as a corporate social responsibility tool in major international corporations. This intersection of law, technology, and corporate responsibility was addressed earlier this month at the World Bank Law, Justice, and Development Week 2019, where the theme was Rights, Technology and Development. The law related to corporate responsibility for sustainable development is increasingly visible due in part to several lawsuits against large international corporations, alleging the use of child and forced labor. In addition, the United Nations has been working for some time on a treaty on business and human rights to encourage corporations to avoid “causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities and [to] address such impacts when they occur.”

DeBeers, Volvo, and Coca-Cola, among other industry leaders, are using blockchain, a technology that allows digital information to be distributed and analyzed, but not copied or manipulated, to trace the source of materials and better manage their supply chains. These initiatives have come as welcome news in industries where child or forced labor in the supply chain can be hard to detect, e.g. conflict minerals, sugar, tobacco, and cacao. The issue is especially difficult when trying to trace the mining of cobalt for lithium ion batteries, increasingly used in electric cars, because the final product is not directly traceable to a single source.

While non governmental organizations (NGOs) have been advocating for improved corporate performance in supply chains regarding labor and environmental standards for years, blockchain may be a technological tool that could reliably trace information regarding various products – from food to minerals – that go through several layers of suppliers before being certified as slave- or child labor- free.

Child labor and forced labor are still common in some countries. The majority of countries worldwide have ratified International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 182, prohibiting the worst forms of child labor (186 ratifications), as well as the ILO Convention prohibiting forced labor (No. 29, with 178 ratifications), and the abolition of forced labor (Convention No. 105, with 175 ratifications). However, the ILO estimates that approximately 40 million men and women are engaged in modern day slavery and 152 million children are subject to child labor, 38% of whom are working in hazardous conditions. The enduring existence of forced labor and child labor raises difficult ethical questions, because in many contexts, the victim does not have a viable alternative livelihood….(More)”.

Henry Farrell at the Crooked Timber: “…So what might a similar analysis say about the marriage of authoritarianism and machine learning? Something like the following, I think. There are two notable problems with machine learning. One – that while it can do many extraordinary things, it is not nearly as universally effective as the mythology suggests. The other is that it can serve as a magnifier for already existing biases in the data. The patterns that it identifies may be the product of the problematic data that goes in, which is (to the extent that it is accurate) often the product of biased social processes. When this data is then used to make decisions that may plausibly reinforce those processes (by singling e.g. particular groups that are regarded as problematic out for particular police attention, leading them to be more liable to be arrested and so on), the bias may feed upon itself.

This is a substantial problem in democratic societies, but it is a problem where there are at least some counteracting tendencies. The great advantage of democracy is its openness to contrary opinions and divergent perspectives. This opens up democracy to a specific set of destabilizing attacks but it also means that there are countervailing tendencies to self-reinforcing biases. When there are groups that are victimized by such biases, they may mobilize against it (although they will find it harder to mobilize against algorithms than overt discrimination). When there are obvious inefficiencies or social, political or economic problems that result from biases, then there will be ways for people to point out these inefficiencies or problems.

These correction tendencies will be weaker in authoritarian societies; in extreme versions of authoritarianism, they may barely even exist. Groups that are discriminated against will have no obvious recourse. Major mistakes may go uncorrected: they may be nearly invisible to a state whose data is polluted both by the means employed to observe and classify it, and the policies implemented on the basis of this data. A plausible feedback loop would see bias leading to error leading to further bias, and no ready ways to correct it. This of course, will be likely to be reinforced by the ordinary politics of authoritarianism, and the typical reluctance to correct leaders, even when their policies are leading to disaster. The flawed ideology of the leader (We must all study Comrade Xi thought to discover the truth!) and of the algorithm (machine learning is magic!) may reinforce each other in highly unfortunate ways.

In short, there is a very plausible set of mechanisms under which machine learning and related techniques may turn out to be a disaster for authoritarianism, reinforcing its weaknesses rather than its strengths, by increasing its tendency to bad decision making, and reducing further the possibility of negative feedback that could help correct against errors. This disaster would unfold in two ways. The first will involve enormous human costs: self-reinforcing bias will likely increase discrimination against out-groups, of the sort that we are seeing against the Uighur today. The second will involve more ordinary self-ramifying errors, that may lead to widespread planning disasters, which will differ from those described in Scott’s account of High Modernism in that they are not as immediately visible, but that may also be more pernicious, and more damaging to the political health and viability of the regime for just that reason….(More)”

Report by Joshua New: “The United States is in the midst of an opioid epidemic 20 years in the making….

One of the most pernicious obstacles in the fight against the opioid epidemic is that, until relatively recently, it was difficult to measure the epidemic in any comprehensive capacity beyond such high-level statistics. A lack of granular data and authorities’ inability to use data to inform response efforts allowed the epidemic to grow to devastating proportions. The maxim “you can’t manage what you can’t measure” has never been so relevant, and this failure to effectively leverage data has undoubtedly cost many lives and caused severe social and economic damage to communities ravaged by opioid addiction, with authorities limited in their ability to fight back.

Many factors contributed to the opioid epidemic, including healthcare providers not fully understanding the potential ramifications of prescribing opioids, socioeconomic conditions that make addiction more likely, and drug distributors turning a blind eye to likely criminal behavior, such as pharmacy workers illegally selling opioids on the black market. Data will not be able to solve these problems, but it can make public health officials and other stakeholders more effective at responding to them. Fortunately, recent efforts to better leverage data in the fight against the opioid epidemic have demonstrated the potential for data to be an invaluable and effective tool to inform decision-making and guide response efforts. Policymakers should aggressively pursue more data-driven strategies to combat the opioid epidemic while learning from past mistakes that helped contribute to the epidemic to prevent similar situations in the future.

The scope of this paper is limited to opportunities to better leverage data to help address problems primarily related to the abuse of prescription opioids, rather than the abuse of illicitly manufactured opioids such as heroin and fentanyl. While these issues may overlap, such as when a person develops an opioid use disorder from prescribed opioids and then seeks heroin when they are unable to obtain more from their doctor, the opportunities to address the abuse of prescription opioids are more clear-cut….(More)”.