Stefaan Verhulst

Press Release: “While researchers from small and medium-sized companies and academic institutions often have enormous numbers of ideas, they don’t always have enough time or resources to develop them all. As a result, many ideas get left behind because companies and academics typically have to focus on narrow areas of research. This is known as the “Innovation Gap”. ESCulab (European Screening Centre: unique library for attractive biology) aims to turn this problem into an opportunity by creating a comprehensive library of high-quality compounds. This will serve as a basis for testing potential research targets against a wide variety of compounds.

Any researcher from a European academic institution or a small to medium-sized enterprise within the consortium can apply for a screening of their potential drug target. If a submitted target idea is positively assessed by a committee of experts it will be run through a screening process and the submitting party will receive a dossier of up to 50 potentially relevant substances that can serve as starting points for further drug discovery activities.

ESCulab will build Europe’s largest collaborative drug discovery platform and is equipped with a total budget of € 36.5 million: Half is provided by the European Union’s Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) and half comes from in-kind contributions from companies of the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries an Associations (EFPIA) and the Medicines for Malaria Venture. It builds on the existing library of the European Lead Factory , which consists of around 200,000 compounds, as well as around 350,000 compounds from EFPIA companies. The European Lead Factory aims to initiate 185 new drug discovery projects through the ESCulab project by screening drug targets against its library.

… The platform has already provided a major boost for drug discovery in Europe and is a strong example of how crowdsourcing, collective intelligence and the cooperation within the IMI framework can create real value for academia, industry, society and patients….(More)”

Blair Sheppard and Ceri-Ann Droog at Strategy and Business: “For the last 70 years the world has done remarkably well. According to the World Bank, the number of people living in extreme poverty today is less than it was in 1820, even though the world population is seven times as large. This is a truly remarkable achievement, and it goes hand in hand with equally remarkable overall advances in wealth, scientific progress, human longevity, and quality of life.

But the organizations that created these triumphs — the most prominent businesses, governments, and multilateral institutions of the post–World War II era — have failed to keep their implicit promises. As a result, today’s leading organizations face a global crisis of legitimacy. For the first time in decades, their influence, and even their right to exist, are being questioned.

Businesses are also being held accountable in new ways for the welfare, prosperity, and health of the communities around them and of the general public. Our own global firm, PwC, is among these businesses. The accusations facing any individual enterprise may or may not be justified, but the broader attitudes underlying them must be taken seriously.

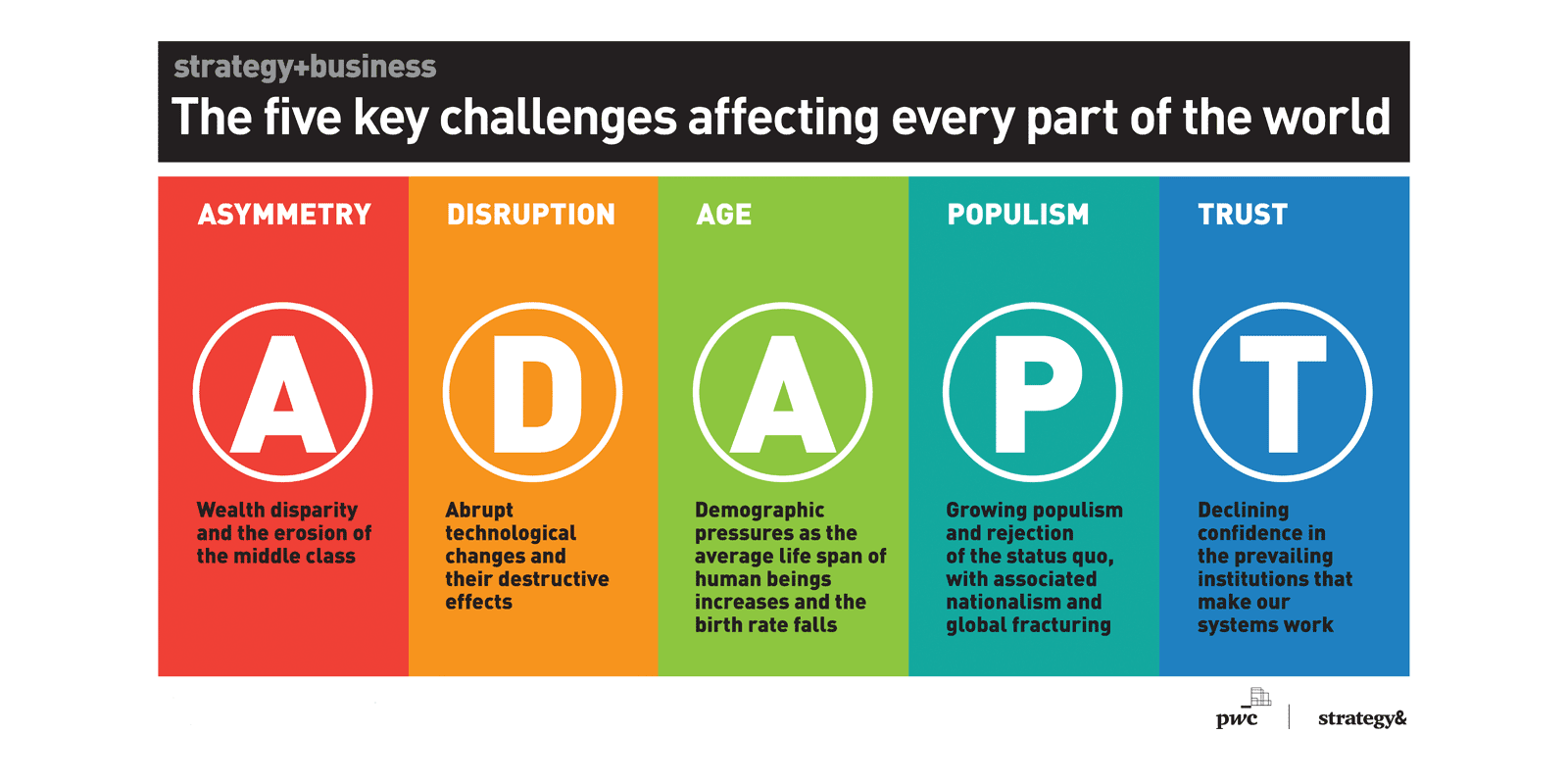

The causes of this crisis of legitimacy have to do with five basic challenges affecting every part of the world:

- Asymmetry: Wealth disparity and the erosion of the middle class

- Disruption: Abrupt technological changes and their destructive effects

- Age: Demographic pressures as the average life span of human beings increases and the birth rate falls

- Populism: Growing populism and rejection of the status quo, with associated nationalism and global fracturing

- Trust: Declining confidence in the prevailing institutions that make our systems work.

(We use the acronym ADAPT to list these challenges because it evokes the inherent change in our time and the need for institutions to respond with new attitudes and behaviors.)

Source: strategy-business.com/ADAPT

A few other challenges, such as climate change and human rights issues, may occur to you as equally important. They are not included in this list because they are not at the forefront of this particular crisis of legitimacy in the same way. But they are affected by it; if leading businesses and global institutions lose their perceived value, it will be harder to address every other issue affecting the world today.

Ignoring the crisis of legitimacy is not an option — not even for business leaders who feel their primary responsibility is to their shareholders. If we postpone solutions too long, we could go past the point of no return: The cost of solving these problems will be too high. Brexit could be a test case. The costs and difficulties of withdrawal could be echoed in other political breakdowns around the world. And if you don’t believe that widespread economic and political disruption is possible right now, then consider the other revolutions and abrupt, dramatic changes in sovereignty that have occurred in the last 250 years, often with technological shifts and widespread dissatisfaction as key factors….(More)”.

Knowledge@Wharton: “Data analytics and artificial intelligence are transforming our lives. Be it in health care, in banking and financial services, or in times of humanitarian crises — data determine the way decisions are made. But often, the way data is collected and measured can result in biased and incomplete information, and this can significantly impact outcomes.

In a conversation with Knowledge@Wharton at the SWIFT Institute Conference on the Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Financial Services Industry, Alexandra Olteanu, a post-doctoral researcher at Microsoft Research, U.S. and Canada, discussed the ethical and people considerations in data collection and artificial intelligence and how we can work towards removing the biases….

….Knowledge@Wharton: Bias is a big issue when you’re dealing with humanitarian crises, because it can influence who gets help and who doesn’t. When you translate that into the business world, especially in financial services, what implications do you see for algorithmic bias? What might be some of the consequences?

Olteanu: A good example is from a new law in the New York state according to which insurance companies can now use social media to decide the level for your premiums. But, they could in fact end up using incomplete information. For instance, you might be buying your vegetables from the supermarket or a farmer’s market, but these retailers might not be tracking you on social media. So nobody knows that you are eating vegetables. On the other hand, a bakery that you visit might post something when you buy from there. Based on this, the insurance companies may conclude that you only eat cookies all the time. This shows how even incomplete data can affect you….(More)”.

Press Release: “EU member states, car manufacturers and navigation systems suppliers will share information on road conditions with the aim of improving road safety. Cora van Nieuwenhuizen, Minister of Infrastructure and Water Management, agreed this today with four other EU countries during the ITS European Congress in Eindhoven. These agreements mean that millions of motorists in the Netherlands will have access to more information on unsafe road conditions along their route.

The data on road conditions that is registered by modern cars is steadily improving. For instance, information on iciness, wrong-way drivers and breakdowns in emergency lanes. This kind of data can be instantly shared with road authorities and other vehicles following the same route. Drivers can then adapt their driving behaviour appropriately so that accidents and delays are prevented….

The partnership was announced today at the ITS European Congress, the largest European event in the fields of smart mobility and the digitalisation of transport. Among other things, various demonstrations were given on how sharing this type of data contributes to road safety. In the year ahead, the car manufacturers BMW, Volvo, Ford and Daimler, the EU member states Germany, the Netherlands, Finland, Spain and Luxembourg, and navigation system suppliers TomTom and HERE will be sharing data. This means that millions of motorists across the whole of Europe will receive road safety information in their car. Talks on participating in the partnership are also being conducted with other European countries and companies.

ADAS

At the ITS congress, Minister Van Nieuwenhuizen and several dozen parties today also signed an agreement on raising awareness of advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) and their safe use. Examples of ADAS include automatic braking systems, and blind spot detection and lane keeping systems. Using these driver assistance systems correctly makes driving a car safer and more sustainable. The agreement therefore also includes the launch of the online platform “slimonderweg.nl” where road users can share information on the benefits and risks of ADAS.

Minister Van Nieuwenhuizen: “Motorists are often unaware of all the capabilities modern cars offer. Yet correctly using driver assistance systems really can increase road safety. From today, dozens of parties are going to start working on raising awareness of ADAS and improving and encouraging the safe use of such systems so that more motorists can benefit from them.”

Connected Transport Corridors

Today at the congress, progress was also made regarding the transport of goods. For example, at the end of this year lorries on three transport corridors in our country will be sharing logistics data. This involves more than just information on environmental zones, availability of parking, recommended speeds and predicted arrival times at terminals. Other new technologies will be used in practice on a large scale, including prioritisation at smart traffic lights and driving in convoy. Preparatory work on the corridors around Amsterdam and Rotterdam and in the southern Netherlands has started…..(More)”.

Chapter by Michiel de Lange in The Right to the Smart City: “The current datafication of cities raises questions about what Lefebvre and many after him have called “the right to the city.” In this contribution, I investigate how the use of data for civic purposes may strengthen the “right to the datafied city,” that is, the degree to which different people engage and participate in shaping urban life and culture, and experience a sense of ownership. The notion of the commons acts as the prism to see how data may serve to foster this participatory “smart citizenship” around collective issues. This contribution critically engages with recent attempts to theorize the city as a commons. Instead of seeing the city as a whole as a commons, it proposes a more fine-grained perspective of the “commons-as-interface.” The “commons-as-interface,” it is argued, productively connects urban data to the human-level political agency implied by “the right to the city” through processes of translation and collectivization. The term is applied to three short case studies, to analyze how these processes engender a “right to the datafied city.” The contribution ends by considering the connections between two seemingly opposed discourses about the role of data in the smart city – the cybernetic view versus a humanist view. It is suggested that the commons-as-interface allows for more detailed investigations of mediation processes between data, human actors, and urban issues….(More)”.

Kiona N. Smith at Forbes: “What could the 107-year-old tragedy of the Titanic possibly have to do with modern problems like sustainable agriculture, human trafficking, or health insurance premiums? Data turns out to be the common thread. The modern world, for better or or worse, increasingly turns to algorithms to look for patterns in the data and and make predictions based on those patterns. And the basic methods are the same whether the question they’re trying to answer is “Would this person survive the Titanic sinking?” or “What are the most likely routes for human trafficking?”

An Enduring Problem

Predicting survival at sea based on the Titanic dataset is a standard practice problem for aspiring data scientists and programmers. Here’s the basic challenge: feed your algorithm a portion of the Titanic passenger list, which includes some basic variables describing each passenger and their fate. From that data, the algorithm (if you’ve programmed it well) should be able to draw some conclusions about which variables made a person more likely to live or die on that cold April night in 1912. To test its success, you then give the algorithm the rest of the passenger list (minus the outcomes) and see how well it predicts their fates.

Online communities like Kaggle.com have held competitions to see who can develop the algorithm that predicts survival most accurately, and it’s also a common problem presented to university classes. The passenger list is big enough to be useful, but small enough to be manageable for beginners. There’s a simple set out of outcomes — life or death — and around a dozen variables to work with, so the problem is simple enough for beginners to tackle but just complex enough to be interesting. And because the Titanic’s story is so famous, even more than a century later, the problem still resonates.

“It’s interesting to see that even in such a simple problem as the Titanic, there are nuggets,” said Sagie Davidovich, Co-Founder & CEO of SparkBeyond, who used the Titanic problem as an early test for SparkBeyond’s AI platform and still uses it as a way to demonstrate the technology to prospective customers….(More)”.

Chapter by Matt Laessig, Bryon Jacob and Carla AbouZahr in The Palgrave Handbook of Global Health Data Methods for Policy and Practice: “…provide best practices for organizations to adopt to disseminate data openly for others to use. They describe development of the open data movement and its rapid adoption by governments, non-governmental organizations, and research groups. The authors provide examples from the health sector—an early adopter—but acknowledge concerns specific to health relating to informed consent, intellectual property, and ownership of personal data. Drawing on their considerable contributions to the open data movement, Laessig and Jacob share their Open Data Progression Model. They describe six stages to make data open: from data collection, documentation of the data, opening the data, engaging the community of users, making the data interoperable, to finally linking the data….(More)”

Announcement: “Healthcare technologies are rapidly evolving, producing new data sources, data types, and data uses, which precipitate more rapid and complex data sharing. Novel technologies—such as artificial intelligence tools and new internet of things (IOT) devices and services—are providing benefits to patients, doctors, and researchers. Data-driven products and services are deepening patients’ and consumers’ engagement and helping to improve health outcomes. Understanding the evolving health data ecosystem presents new challenges for policymakers and industry. There is an increasing need to better understand and document the stakeholders, the emerging data types and their uses.

The Future of Privacy Forum (FPF) and the Information Accountability Foundation (IAF) partnered to form the FPF-IAF Joint Health Initiative in 2018. Today, the Initiative is releasing A Taxonomy of Definitions for the Health Data Ecosystem; the publication is intended to enable a more nuanced, accurate, and common understanding of the current state of the health data ecosystem. The Taxonomy outlines the established and emerging language of the health data ecosystem. The Taxonomy includes definitions of:

- The stakeholders currently involved in the health data ecosystem and examples of each;

- The common and emerging data types that are being collected, used, and shared across the health data ecosystem;

- The purposes for which data types are used in the health data ecosystem; and

- The types of actions that are now being performed and which we anticipate will be performed on datasets as the ecosystem evolves and expands.

This report is as an educational resource that will enable a deeper understanding of the current landscape of stakeholders and data types….(More)”.

Jukka Vahti at Sitra: “The Finnish tradition of establishing, maintaining and developing data registers goes back to the 1600s, when parish records were first kept.

When this old custom is combined with the opportunities afforded by digitisation, the positive approach Finns have towards research and technology, and the recently updated legislation enabling the data economy, Finland and the Finnish people can lead the way as Europe gradually, or even suddenly, switches to a fair data economy.

The foundations for a fair data economy already exist

The fair data economy is a natural continuation of the former projects promoting e-services that were undertaken in Finland.

For example, the Data Exchange Layer is already speeding up the transfer of data from one system to another in Finland and in Estonia, the country where the system originated, and a system unique to just these two countries.

In May 2019 Finland also saw the entry into force of the Act on the Secondary Use of Health and Social Data, according to which the information on social welfare and healthcare held in registers may be used for purposes of statistics, research, education, knowledge management, control and supervision conducted by authorities, and development and innovation activity.

The new law will make the work of researchers and service developers more effective, as the business of acquiring a permit will take place through a one-stop-shop principle and it will be possible to use data from more than one source more readily than before….(More)”.

TedX Talk by Gianluca Sgueo: “How does gaming link people in today society? In business, companies use gamification as a marketing tool to attract customer; while government and non-governmental organizations deploy it to connect citizens and public powers. Gianluca Sgueo, a global professor major in public law and policy analyst, tells us how a gamified government facilitates and engages the citizens in the policy-making process; as well as its inconspicuous but important impacts brought to our lives. Gianluca Sgueo is Global Media Professor at New York University in Florence, Visiting Professor at HEC Paris and Research Associate at the Center of Social Studies of the University of Coimbra. His area of expertise is the public sector, to which he provides professional services. His academic work focuses on participatory democracy, lobbying and globalization and he is author of a recent work about Games, Powers & Democracies….(More)