Stefaan Verhulst

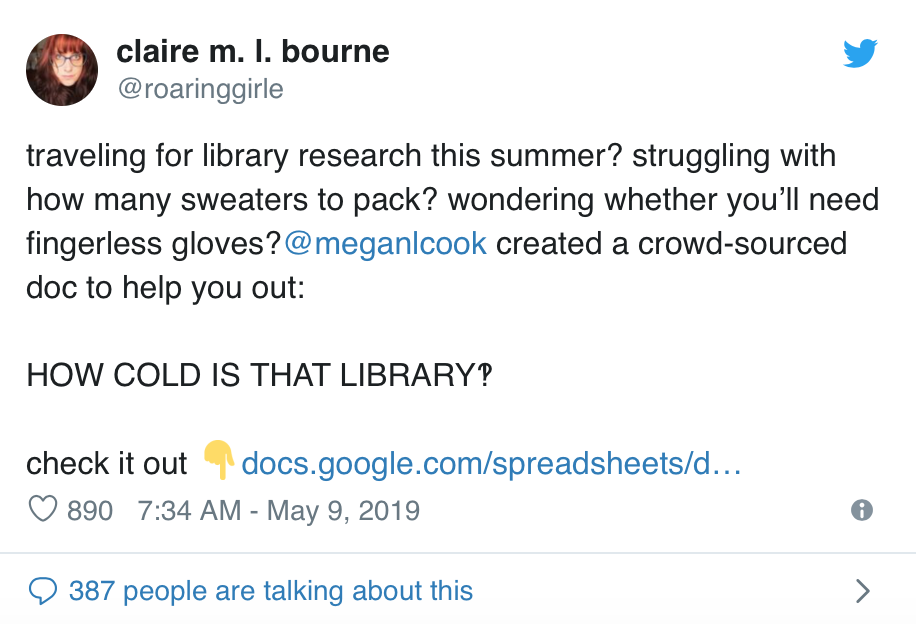

Colleen Flaherty at Inside Higher Ed: “What a difference preparation makes when it comes to doing research in Arctic-level air-conditioned academic libraries (or ones that are otherwise freezing — or not air-conditioned at all). Luckily, Megan L. Cook, assistant professor of English at Colby College, published a crowdsourced document called“How Cold Is that Library?” ….

Cook, who was not immediately available for comment, has said the document was group effort. Juliet Sperling, a faculty fellow in American art at Colby, credited her colleague’s “brilliance” but said the document was “generally inspired by conversations we’ve had as co-fellows” in the Andrew W. Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography. The society brings together 60-some scholars of rare books and material texts from a variety of disciplinary or institutional approaches, she said, “so collectively, we’ve all spent quite a bit of time in libraries of various climates all over the world.” In addition to library temperatures, lighting and even humidity levels, the scholars trade research destinations’ photo policies and nearby eateries and drinking holes, among other tips. A spreadsheet opens up that resource to others, Sperling said. …(More)”.

Brandi Vincent at NextGov: “While government leaders across the globe are excited about the unleashing artificial intelligence in their organizations, most are struggling with deploying it for their missions because they can’t wrangle their data, a new study suggests.

In a survey released this week, Splunk and TRUE Global Intelligence polled 1,365 global business managers and IT leaders across seven countries. The research indicates that the majority of organizations’ data is “dark,” or unquantified, untapped and usually generated by systems, devices or interactions.

AI runs on data and yet few organizations seem to be able to tap into its value—or even find it.

“Neglected by business and IT managers, dark data is an underused asset that demands a more sophisticated approach to how organizations collect, manage and analyze information,” the report said. “Yet respondents also voiced hesitance about diving in.”

A third of respondents said more than 75% of their organizations’ data is dark and only one in every nine people reports that less than a quarter of their organizations’ data is dark.

Many of the global respondents said a lack of interest from their leadership makes it hard to recover dark data. Another 60% also said more than half of their organizations’ data is not captured and “much of it is not even understood to exist.”

Research also suggests that while almost 100% of respondents believe data skills are critical for jobs in the future, more than half feel too old to learn new skills and 69% are content to keep doing what they are doing, even if it means they won’t be promoted.

“Many say they’d be content to let others take the lead, even at the expense of their own career progress,” the report said.

More than half of the respondents said they don’t understand AI well, as it’s still in its early stages, and 39% said their colleagues and industry don’t get it either. They said few organizations are deploying the new tech right now, but the majority of respondents do see its potential….(More)”.

News Release: “In the wake of the 2016 American presidential election, western media outlets have become almost obsessed with echo chambers. With headlines like “Echo Chambers are Dangerous” and “Are You in a Social Media Echo Chamber?,” news media consumers have been inundated by articles discussing the problems with spending most of one’s time around likeminded people.

But are social bubbles really all that bad? Perhaps not.

A new study from the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and the School of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that collective intelligence — peer learning within social networks — can increase belief accuracy even in politically homogenous groups.

“Previous research showed that social information processing could work in mixed groups,” says lead author and Annenberg alum Joshua Becker (Ph.D. ’18), who is currently a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. “But theories of political polarization argued that social influence within homogenous groups should only amplify existing biases.”

It’s easy to imagine that networked collective intelligence would work when you’re asking people neutral questions, such as how many jelly beans are in a jar. But what about probing hot button political topics? Because people are more likely to adjust the facts of the world to match their beliefs than vice versa, prior theories claimed that a group of people who agree politically would be unable to use collective reasoning to arrive at a factual answer if it challenges their beliefs.

“Earlier this year, we showed that when Democrats and Republicans interact with each other within properly designed social media networks, it can eliminate polarization and improve both groups’ understanding of contentious issues such as climate change,” says senior author Damon Centola, Associate Professor of Communication at the Annenberg School. “Remarkably, our new findings show that properly designed social media networks can even lead to improved understanding of contentious topics within echo chambers.”

Becker and colleagues devised an experiment in which participants answered fact-based questions that stir up political leanings, like “How much did unemployment change during Barack Obama’s presidential administration?” or “How much has the number of undocumented immigrants changed in the last 10 years?” Participants were placed in groups of only Republicans or only Democrats and given the opportunity to change their responses based on the other group members’ answers.

The results show that individual beliefs in homogenous groups became 35% more accurate after participants exchanged information with one another. And although people’s beliefs became more similar to their own party members, they also became more similar to members of the other political party, even without any between-group exchange. This means that even in homogenous groups — or echo chambers — social influence increases factual accuracy and decreases polarization.

“Our results cast doubt on some of the gravest concerns about the role of echo chambers in contemporary democracy,” says co-author Ethan Porter, Assistant Professor of Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. “When it comes to factual matters, political echo chambers need not necessarily reduce accuracy or increase polarization. Indeed, we find them doing the opposite….(More)… (Full Paper: “The Wisdom of Partisan Crowds“)

Paper by Steven Feldstein: “Across the world, artificial intelligence (AI) is showing its potential for abetting repressive regimes and upending the relationship between citizen and state, thereby exacerbating a global resurgence of authoritarianism. AI is a component in a broader ecosystem of digital repression, but it is relevant to several different techniques, including surveillance, censorship, disinformation, and cyber attacks. AI offers three distinct advantages to autocratic leaders: it helps solve principal-agent loyalty problems, it offers substantial cost-efficiencies over traditional means of surveillance, and it is particularly effective against external regime challenges. China is a key proliferator of AI technology to authoritarian and illiberal regimes; such proliferation is an important component of Chinese geopolitical strategy. To counter the spread of high-tech repression abroad, as well as potential abuses at home, policy makers in democratic states must think seriously about how to mitigate harms and to shape better practices….(More)”

Research Paper by Roya Pakzad: “Efforts are being made to use information and communications technologies (ICTs) to improve accountability in providing refugee aid. However, there remains a pressing need for increased accountability and transparency when designing and deploying humanitarian technologies. This paper outlines the challenges and opportunities of emerging technologies, such as machine learning and blockchain, in the refugee system.

The paper concludes by recommending the creation of quantifiable metrics for sharing information across both public and private initiatives; the creation of the equivalent of a “Hippocratic oath” for technologists working in the humanitarian field; the development of predictive early-warning systems for human rights abuses; and greater accountability among funders and technologists to ensure the sustainability and real-world value of humanitarian apps and other digital platforms….(More)”

Book by Carmit Wiesslitz: “What role does the Internet play in the activities of organizations for social change? This book examines to what extent the democratic potential ascribed to the Internet is realized in practice, and how civil society organizations exploit the unique features of the Internet to attain their goals. This is the story of the organization members’ outlooks and impressions of digital platforms’ role as tools for social change; a story that debunks a common myth about the Internet and collective action. In a time when social media are credited with immense power in generating social change, this book serves as an important reminder that reality for activists and social change organizations is more complicated. Thus, the book sheds light on the back stage of social change organizations’ operations as they struggle to gain visibility in the infinite sea of civil groups competing for attention in the online public sphere. While many studies focus on the performative dimension of collective action (such as protests), this book highlights the challenges of these organizations’ mundane routines. Using a unique analytical perspective based on a structural-organizational approach, and a longitudinal study that utilizes a decade worth of data related to the specific case of Israel and its highly conflicted and turbulent society, the book makes a significant contribution to study of new media and to theories of Internet, democracy, and social change….(More)”.

Special Issue of The Atlantis: “Across the political spectrum, a consensus has arisen that Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other digital platforms are laying ruin to public discourse. They trade on snarkiness, trolling, outrage, and conspiracy theories, and encourage tribalism, information bubbles, and social discord. How did we get here, and how can we get out? The essays in this symposium seek answers to the crisis of “digital discourse” beyond privacy policies, corporate exposés, and smarter algorithms.

The Inescapable Town Square

L. M. Sacasas on how social media combines the worst parts of past eras of communication

Preserving Real-Life Childhood

Naomi Schaefer Riley on why decency online requires raising kids who know life offline

How Not to Regulate Social Media

Shoshana Weissmann on proposed privacy and bot laws that would do more harm than good

The Four Facebooks

Nolen Gertz on misinformation, manipulation, dependency, and distraction

Do You Know Who Your ‘Friends’ Are?

Ashley May on why treating others well online requires defining our relationships

The Distance Between Us

Micah Meadowcroft on why we act badly when we don’t speak face-to-face

The Emergent Order of Twitter

Andy Smarick on why the platform should be fixed from the bottom up, not the top down

Imagine All the People

James Poulos on how the fantasies of the TV era created the disaster of social media

Making Friends of Trolls

Caitrin Keiper on finding familiar faces behind the black mirror…(More)”

Paper by Anthea Van der Hoogen, Brenda Scholtz and Andre Calitz: “Cities globally are facing an increasing forecasted citizen growth for the next decade. It has therefore become a necessity for cities to address their initiatives in smarter ways to overcome the challenges of possible extinction of resources. Cities in South Africa are trying to involve stakeholders to help address these challenges. Stakeholders are an important component in any smart city initiatives. The purpose of this paper is to report on a review of existing literature related to smart cities, and to propose a Smart City Stakeholder Classification Model. The common dimensions of smart cities are identified and the roles of the various stakeholders are classified according to these dimensions in the model. Nine common dimensions and related factors were identified through an analysis of existing frameworks for smart cities. The model was then used to identify and classify the stakeholders participating in two smart city projects in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa….(More)”.

Essay by James D’Angelo and Brent Ranalli in Foreign Affairs: “…76 percent of Americans, according to a Gallup poll, disapprove of Congress.

This dysfunction started well before the Trump presidency. It has been growing for decades, despite promise after promise and proposal after proposal to reverse it. Many explanations have been offered, from the rise of partisan media to the growth of gerrymandering to the explosion of corporate money. But one of the most important causes is usually overlooked: transparency. Something usually seen as an antidote to corruption and bad government, it turns out, is leading to both.

The problem began in 1970, when a group of liberal Democrats in the House of Representatives spearheaded the passage of new rules known as “sunshine reforms.” Advertised as measures that would make legislators more accountable to their constituents, these changes increased the number of votes that were recorded and allowed members of the public to attend previously off-limits committee meetings.

But the reforms backfired. By diminishing secrecy, they opened up the legislative process to a host of actors—corporations, special interests, foreign governments, members of the executive branch—that pay far greater attention to the thousands of votes taken each session than the public does. The reforms also deprived members of Congress of the privacy they once relied on to forge compromises with political opponents behind closed doors, and they encouraged them to bring useless amendments to the floor for the sole purpose of political theater.

Fifty years on, the results of this experiment in transparency are in. When lawmakers are treated like minors in need of constant supervision, it is special interests that benefit, since they are the ones doing the supervising. And when politicians are given every incentive to play to their base, politics grows more partisan and dysfunctional. In order for Congress to better serve the public, it has to be allowed to do more of its work out of public view.

The idea of open government enjoys nearly universal support. Almost every modern president has paid lip service to it. (Even the famously paranoid Richard Nixon said, “When information which properly belongs to the public is systematically withheld by those in power, the people soon become ignorant of their own affairs, distrustful of those who manage them, and—eventually—incapable of determining their own destinies.”) From former Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan to Democratic Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, from the liberal activist Ralph Nader to the anti-tax crusader Grover Norquist, all agree that when it comes to transparency, more is better.

It was not always this way. It used to be that secrecy was seen as essential to good government, especially when it came to crafting legislation. …(More)”

Report by the Public Affairs Council: “Millions of citizens and thousands of organizations contact Congress each year to urge Senators and House members to vote for or against legislation. Countless others weigh in with federal agencies on regulatory issues ranging from healthcare to livestock grazing rights. Congressional and federal agency personnel are inundated with input. So how do staff know what to believe? Who do they trust? And which methods of communicating with government seem to be most effective? To find out, the Public Affairs Council teamed up with Morning Consult in an online survey of 173 congressional and federal employees. Participants were asked for their views on social media, fake news, influential methods of communication and trusted sources of policy information.

When asked to compare the effectiveness of different advocacy techniques, congressional staff rate personal visits to Washington, D.C., (83%) or district offices (81%), and think tank reports (81%) at the top of the list. Grassroots advocacy techniques such as emails, phone calls and postal mail campaigns also score above 75% for effectiveness.

Traditional in-person visits from lobbyists are considered effective by a strong majority (75%), as are town halls (73%) and lobby days (72%). Of the 13 options considered, the lowest score goes to social media posts, which are still rated effective by 57% of survey participants.

Despite their unpopularity with the general public, corporate CEOs are an asset when it comes to getting meetings scheduled with members of Congress. Eighty-three percent (83%) of congressional staffers say their boss would likely meet with a CEO from their district or state when that executive comes to Washington, D.C., compared with only 7% who say their boss would be unlikely to take the meeting….(More)”.