Stefaan Verhulst

Paper by Ann-Kathrin Koessler and Stefanie Engel: “This paper discusses how policy interventions not only alter the legal and financial framework in which an individual is operating, but can also lead to changes in relevant beliefs. We argue that such belief changes in how an individual perceives herself, relevant others, the regulator and/or the activity in question can lead to behavioral changes that were neither intended nor expected when the policy was designed.

In the environmental economics literature, these secondary impacts of conventional policy interventions have not been systematically reviewed. Hence, we intend to raise awareness of these effects. In this paper, we review relevant research from behavioral economics and psychology, and identify and discuss the domains for which beliefs can change. Lastly, we discuss design options with which an undesired change in beliefs can be avoided when a new policy is put into practice….(More)”

Paper by Anne L. Washington: “The United States optimizes the efficiency of its growing criminal justice system with algorithms however, legal scholars have overlooked how to frame courtroom debates about algorithmic predictions. In State v Loomis, the defense argued that the court’s consideration of risk assessments during sentencing was a violation of due process because the accuracy of the algorithmic prediction could not be verified. The Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the consideration of predictive risk at sentencing because the assessment was disclosed and the defendant could challenge the prediction by verifying the accuracy of data fed into the algorithm.

Was the court correct about how to argue with an algorithm?

The Loomis court ignored the computational procedures that processed the data within the algorithm. How algorithms calculate data is equally as important as the quality of the data calculated. The arguments in Loomis revealed a need for new forms of reasoning to justify the logic of evidence-based tools. A “data science reasoning” could provide ways to dispute the integrity of predictive algorithms with arguments grounded in how the technology works.

This article’s contribution is a series of arguments that could support due process claims concerning predictive algorithms, specifically the Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (“COMPAS”) risk assessment. As a comprehensive treatment, this article outlines the due process arguments in Loomis, analyzes arguments in an ongoing academic debate about COMPAS, and proposes alternative arguments based on the algorithm’s organizational context….(More)”

Blog post by Frances Foley: “..In July 2016, the new government – led by Fine Gael, backed by independents – put forward a bill to establish a national-level Citizens’ Assembly to look at the biggest issues of the day. These included the challenges of an ageing population; the role fixed-term parliaments; referendums; the 8th Amendment on abortion; and climate change.

Citizens from every region, every socio-economic background, each ethnicity and age group and from right across the spectrum of political opinion convened over the course of two weekends between September and November 2017. The issue seemed daunting in scale and complexity, but the participants had been well-briefed and had at their disposal a line up of experts, scientists, advocates and other witnesses who would help them make sense of the material. By the end, citizens had produced a radical series of recommendations which went far beyond what any major Irish party was promising, surprising even the initiators of the process….

As expected, the passage for some of the proposals through the Irish party gauntlet has not been smooth. The 8-hour long debate on increasing the carbon tax, for example, suggests that mixing deliberative and representative democracy still produces conflict and confusion. It is certainly clear that parliaments have to adapt and develop if citizens’ assemblies are ever to find their place in our modern democracies.

But the most encouraging move has been the simple acknowledgement that many of the barriers to implementation lie at the level of governance. The new Climate Action Commission, with a mandate to monitor climate action across government, should act as the governmental guarantor of the vision from the Citizens’ Assembly. Citizens’ proposals have themselves stimulated a review of internal government processes to stop their demands getting mired in party wrangling and government bureaucracy. By their very nature, the success of citizens’ assemblies can also provide an alternative vision of how decisions can be made – and in so doing shame political parties and parliaments into improving their decision-making practices.

Does the Irish Citizens’ Assembly constitute a case of rapid transition? In terms of its breadth, scale and vision, the experiment is impressive. But in terms of speed, deliberative processes are often criticised for being slow, unwieldly and costly. The response to this should be to ask what we’re getting: whilst an Assembly is not the most rapid vehicle for change – most serious processes take several months, if not a couple of years – the results, both in specific outcomes and in cultural or political shifts – can be astounding….

In respect to climate change, this harmony between ends and means is particularly significant. The climate crisis is the most severe collective decision-making challenge of our times, one that demands courage, but also careful thought….(More)”.

Pew Research Center: “Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years. Anti-establishment leaders, parties and movements have emerged on both the right and left of the political spectrum, in some cases challenging fundamental norms and institutions of liberal democracy. Organizations from Freedom House to the Economist Intelligence Unit to V-Demhave documented global declines in the health of democracy.

As previous Pew Research Center surveys have illustrated, ideas at the core of liberal democracy remain popular among global publics, but commitment to democracy can nonetheless be weak. Multiple factors contribute to this lack of commitment, including perceptions about how well democracy is functioning. And as findings from a new Pew Research Center survey show, views about the performance of democratic systems are decidedly negative in many nations. Across 27 countries polled, a median of 51% are dissatisfied with how democracy is working in their country; just 45% are satisfied.

Assessments of how well democracy is working vary considerably across nations. In Europe, for example, more than six-in-ten Swedes and Dutch are satisfied with the current state of democracy, while large majorities in Italy, Spain and Greece are dissatisfied.

To better understand the discontent many feel with democracy, we asked people in the 27 nations studied about a variety of economic, political, social and security issues. The results highlight some key areas of public frustration: Most believe elections bring little change, that politicians are corrupt and out of touch and that courts do not treat people fairly. On the other hand, people are more positive about how well their countries protect free expression, provide economic opportunity and ensure public safety.

We also asked respondents about other topics, such as the state of the economy, immigration and attitudes toward major political parties. And in Europe, we included additional questions about immigrants and refugees, as well as opinions about the European Union….(More)”.

Book by Philipp Herold: “In today’s world, we cooperate across legal and cultural systems in order to create value. However, this increases volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity as challenges for societies, politics, and business. This has made governance a scarce resource. It thus is inevitable that we understand the means of governance available to us and are able to economize on them. Trends like the increasing role of product labels and a certification industry as well as political movements towards nationalism and conservatism may be seen as reaction to disappointments from excessive cooperation. To avoid failures of cooperation, governance is important – control through e.g. contracts is limited and in governance economics trust is widely advertised without much guidance on its preconditions or limits.

This book draws on the rich insight from research on trust and control, and accommodates the key results for governance considerations in an institutional economics framework. It provides a view on the limits of cooperation from the required degree of governance, which can be achieved through extrinsic motivation or building on intrinsic motivation. Trust Control Economics thus inform a more realistic expectation about the net value added from cooperation by providing a balanced view including the cost of governance. It then becomes clear how complex cooperation is about ‘governance accretion’ where limited trustworthiness is substituted by control and these control instances need to be governed in turn.

Trust, Control, and the Economics of Governance is a highly necessary development of institutional economics to reflect progress made in trust research and is a relevant addition for practitioners to better understand the role of trust in the governance of contemporary cooperation-structures. It will be of interest to researchers, academics, and students in the fields of economics and business management, institutional economics, and business ethics….(More)”.

Press release: “The Partnership on AI (PAI) has today published a report gathering the views of the multidisciplinary artificial intelligence and machine learning research and ethics community which documents the serious shortcomings of algorithmic risk assessment tools in the U.S. criminal justice system. These kinds of AI tools for deciding on whether to detain or release defendants are in widespread use around the United States, and some legislatures have begun to mandate their use. Lessons drawn from the U.S. context have widespread applicability in other jurisdictions, too, as the international policymaking community considers the deployment of similar tools.

While criminal justice risk assessment tools are often simpler than the deep neural networks used in many modern artificial intelligence systems, they are basic forms of AI. As such, they present a paradigmatic example of the high-stakes social and ethical consequences of automated AI decision-making….

Across the report, challenges to using these tools fell broadly into three primary categories:

- Concerns about the accuracy, bias, and validity in the tools themselves

- Although the use of these tools is in part motivated by the desire to mitigate existing human fallibility in the criminal justice system, this report suggests that it is a serious misunderstanding to view tools as objective or neutral simply because they are based on data.

- Issues with the interface between the tools and the humans who interact with them

- In addition to technical concerns, these tools must be held to high standards of interpretability and explainability to ensure that users (including judges, lawyers, and clerks, among others) can understand how the tools’ predictions are reached and make reasonable decisions based on these predictions.

- Questions of governance, transparency, and accountability

- To the extent that such systems are adapted to make life-changing decisions, tools and decision-makers who specify, mandate, and deploy them must meet high standards of transparency and accountability.

This report highlights some of the key challenges with the use of risk assessment tools for criminal justice applications. It also raises some deep philosophical and procedural issues which may not be easy to resolve. Surfacing and addressing those concerns will require ongoing research and collaboration between policymakers, the AI research community, civil society groups, and affected communities, as well as new types of data collection and transparency. It is PAI’s mission to spur and facilitate these conversations and to produce research to bridge such gaps….(More)”

Daanish Masood & Martin Waehlisch at the United Nations University: “At the United Nations, we have been exploring completely different scenarios for AI: its potential to be used for the noble purposes of peace and security. This could revolutionize the way of how we prevent and solve conflicts globally.

Two of the most promising areas are Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing. Machine Learning involves computer algorithms detecting patterns from data to learn how to make predictions and recommendations. Natural Language Processing involves computers learning to understand human languages.

At the UN Secretariat, our chief concern is with how these emerging technologies can be deployed for the good of humanity to de-escalate violence and increase international stability.

This endeavor has admirable precedent. During the Cold War, computer scientists used multilayered simulations to predict the scale and potential outcome of the arms race between the East and the West.

Since then, governments and international agencies have increasingly used computational models and advanced Machine Learning to try to understand recurrent conflict patterns and forecast moments of state fragility.

But two things have transformed the scope for progress in this field.

The first is the sheer volume of data now available from what people say and do online. The second is the game-changing growth in computational capacity that allows us to crunch unprecedented, inconceivable quantities data with relative speed and ease.

So how can this help the United Nations build peace? Three ways come to mind.

Firstly, overcoming cultural and language barriers. By teaching computers to understand human language and the nuances of dialects, not only can we better link up what people write on social media to local contexts of conflict, we can also more methodically follow what people say on radio and TV. As part of the UN’s early warning efforts, this can help us detect hate speech in a place where the potential for conflict is high. This is crucial because the UN often works in countries where internet coverage is low, and where the spoken languages may not be well understood by many of its international staff.

Natural Language Processing algorithms can help to track and improve understanding of local debates, which might well be blind spots for the international community. If we combine such methods with Machine Learning chatbots, the UN could conduct large-scale digital focus groups with thousands in real-time, enabling different demographic segments in a country to voice their views on, say, a proposed peace deal – instantly testing public support, and indicating the chances of sustainability.

Secondly, anticipating the deeper drivers of conflict. We could combine new imaging techniques – whether satellites or drones – with automation. For instance, many parts of the world are experiencing severe groundwater withdrawal and water aquifer depletion. Water scarcity, in turn, drives conflicts and undermines stability in post-conflict environments, where violence around water access becomes more likely, along with large movements of people leaving newly arid areas.

One of the best predictors of water depletion is land subsidence or sinking, which can be measured by satellite and drone imagery. By combining these imaging techniques with Machine Learning, the UN can work in partnership with governments and local communities to anticipate future water conflicts and begin working proactively to reduce their likelihood.

Thirdly, advancing decision making. In the work of peace and security, it is surprising how many consequential decisions are still made solely on the basis of intuition.

Yet complex decisions often need to navigate conflicting goals and undiscovered options, against a landscape of limited information and political preference. This is where we can use Deep Learning – where a network can absorb huge amounts of public data and test it against real-world examples on which it is trained while applying with probabilistic modeling. This mathematical approach can help us to generate models of our uncertain, dynamic world with limited data.

With better data, we can eventually make better predictions to guide complex decisions. Future senior peace envoys charged with mediating a conflict would benefit from such advances to stress test elements of a peace agreement. Of course, human decision-making will remain crucial, but would be informed by more evidence-driven robust analytical tools….(More)”.

Book edited by Anna Visvizi and Miltiadis D. Lytras: “Advances in information and communication technology (ICT) have directly impacted the way in which politics operates today. Bringing together research on Europe, the US, South America, the Middle East, Asia and Africa, this book examines the relationship between ICT and politics in a global perspective.

Technological innovations such as big data, data mining, sentiment analysis, cognitive computing, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, augmented reality, social media and blockchain technology are reshaping the way ICT intersects with politics and in this collection contributors examine these developments, demonstrating their impact on the political landscape. Chapters examine topics such as cyberwarfare and propaganda, post-Soviet space, Snowden, US national security, e-government, GDPR, democratization in Africa and internet freedom.

Providing an overview of new research on the emerging relationship between the promise and potential inherent in ICT and its impact on politics, this edited collection will prove an invaluable text for students, researchers and practitioners working in the fields of Politics, International Relations and Computer Science…..(More)”

Mark Puente in The Los Angeles Times: “The Los Angeles Police Department pioneered the controversial use of data to pinpoint crime hot spots and track violent offenders.

Complex algorithms and vast databases were supposed to revolutionize crime fighting, making policing more efficient as number-crunching computers helped to position scarce resources.

But critics long complained about inherent bias in the data — gathered by officers — that underpinned the tools.

They claimed a partial victory when LAPD Chief Michel Moore announced he would end one highly touted program intended to identify and monitor violent criminals. On Tuesday, the department’s civilian oversight panel raised questions about whether another program, aimed at reducing property crime, also disproportionately targets black and Latino communities.

Members of the Police Commission demanded more information about how the agency plans to overhaul a data program that helps predict where and when crimes will likely occur. One questioned why the program couldn’t be suspended.

“There is very limited information” on the program’s impact, Commissioner Shane Murphy Goldsmith said.

The action came as so-called predictive policing— using search tools, point scores and other methods — is under increasing scrutiny by privacy and civil liberties groups that say the tactics result in heavier policing of black and Latino communities. The argument was underscored at Tuesday’s commission meeting when several UCLA academics cast doubt on the research behind crime modeling and predictive policing….(More)”.

Blog by Andrew Young and Stefaan Verhulst: “Earlier this year we launched the Contracts for Data Collaboration (C4DC) initiative — an open collaborative with charter members from The GovLab, UN SDSN Thematic Research Network on Data and Statistics (TReNDS), University of Washington and the World Economic Forum. C4DC seeks to address the inefficiencies of developing contractual agreements for public-private data collaboration by informing and guiding those seeking to establish a data collaborative by developing and making available a shared repository of relevant contractual clauses taken from existing legal agreements. Today TReNDS published “Partnerships Founded on Trust,” a brief capturing some initial findings from the C4DC initiative.

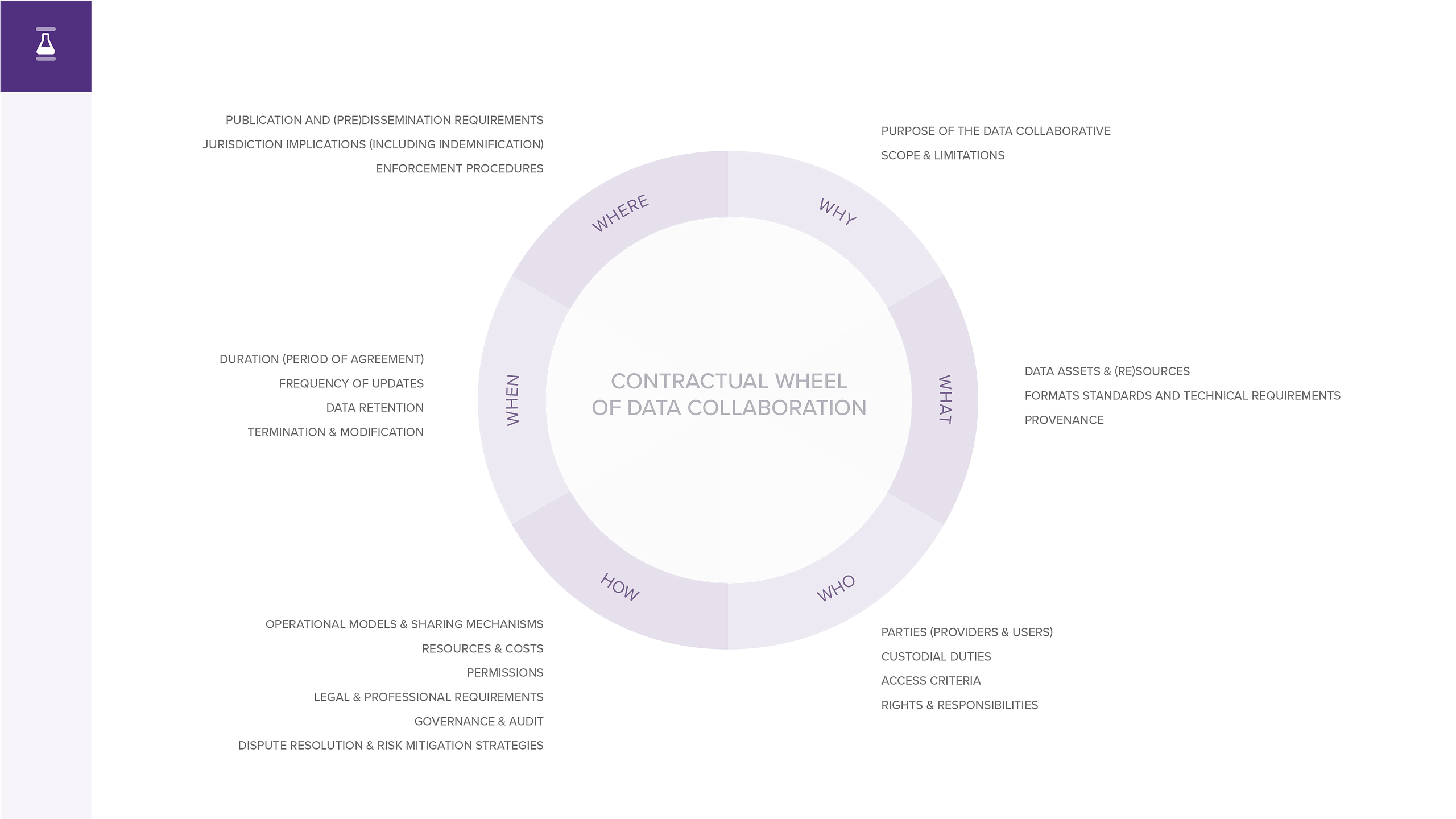

The Contractual Wheel of Data Collaboration [beta]

As part of the C4DC effort, and to support Data Stewards in the private sector and decision-makers in the public and civil sectors seeking to establish Data Collaboratives, The GovLab developed the Contractual Wheel of Data Collaboration [beta]. The Wheel seeks to capture key elements involved in data collaboration while demystifying contracts and moving beyond the type of legalese that can create confusion and barriers to experimentation.

The Wheel was developed based on an assessment of existing legal agreements, engagement with The GovLab-facilitated Data Stewards Network, and analysis of the key elements of our Data Collaboratives Methodology. It features 22 legal considerations organized across 6 operational categories that can act as a checklist for the development of a legal agreement between parties participating in a Data Collaborative:…(More)”.