Stefaan Verhulst

Gabriella Capone at apolitical (a winner of the 2018 Apolitical Young Thought Leaders competition): “Rain ravaged Gdańsk in 2016, taking the lives of two residents and causing millions of euros in damage. Despite its 700-year history of flooding the city was overwhelmed by these especially devastating floods. Also, Gdańsk is one of the European coasts most exposed to rising sea levels. It needed a new approach to avoid similar outcomes for the next, inevitable encounter with this worsening problem.

Bringing in citizens to tackle such a difficult issue was not the obvious course of action. Yet this was the proposal of Dr. Marcin Gerwin, an advocate from a neighbouring town who paved the way for Poland’s first participatory budgeting experience.

Mayor Adamowicz of Gdańsk agreed and, within a year, they welcomed about 60 people to the first Citizens Assembly on flood mitigation. Implemented by Dr. Gerwin and a team of coordinators, the Assembly convened over four Saturdays, heard expert testimony, and devised solutions.

The Assembly was not only deliberative and educational, it was action-oriented. Mayor Adamowicz committed to implement proposals on which 80% or more of participants agreed. The final 16 proposals included the investment of nearly $40 million USD in monitoring systems and infrastructure, subsidies to incentivise individuals to improve water management on their property, and an educational “Do Not Flood” campaign to highlight emergency resources.

It may seem risky to outsource the solving of difficult issues to citizens. Yet, when properly designed, public problem-solving can produce creative resolutions to formidable challenges. Beyond Poland, public problem-solving initiatives in Mexico and the United States are making headway on pervasive issues, from flooding to air pollution, to technology in public spaces.

The GovLab, with support from the Tinker Foundation, is

Aaron Smith at the Pew Research Center: “Algorithms are all around us, utilizing massive stores of data and complex analytics to make decisions with often significant impacts on humans. They recommend books and movies for us to read and watch, surface news stories they think we might find relevant, estimate the likelihood that a tumor is cancerous and predict whether someone might be a criminal or a worthwhile credit risk. But despite the growing presence of algorithms in many aspects of daily life, a Pew Research Center survey of U.S. adults finds that the public is frequently skeptical of these tools when used in various real-life situations.

This skepticism spans several dimensions. At a broad level, 58% of Americans feel that computer programs will always reflect some level of human bias – although 40% think these programs can be designed in a way that is bias-free. And in various contexts, the public worries that these tools might violate privacy, fail to capture the nuance of complex situations, or simply put the people they are evaluating in an unfair situation. Public perceptions of algorithmic decision-making are also often highly contextual. The survey shows that otherwise similar technologies can be viewed with support or suspicion depending on the circumstances or on the tasks they are assigned to do….

The following are among the major findings.

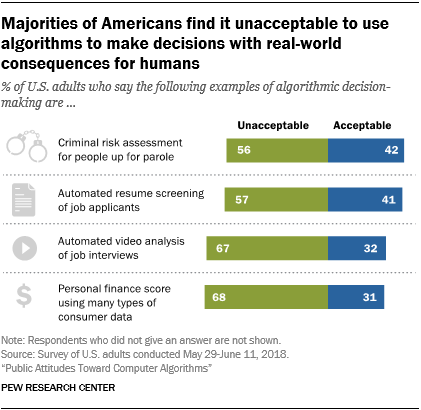

The public expresses broad concerns about the fairness and acceptability of using computers for decision-making in situations with important real-world consequences

By and large, the public views these examples of algorithmic decision-making as unfair to the people the computer-based systems are evaluating. Most notably, only around one-third of Americans think that the video job interview and personal finance score algorithms would be fair to job applicants and consumers. When asked directly whether they think the use of these algorithms is acceptable, a majority of the public says that they are not acceptable. Two-thirds of Americans (68%) find the personal finance score algorithm unacceptable, and 67% say the computer-aided video job analysis algorithm is unacceptable….

Attitudes toward algorithmic decision-making can depend heavily on context

Despite the consistencies in some of these responses, the survey also highlights the ways in which Americans’ attitudes toward algorithmic decision-making can depend heavily on the context of those decisions and the characteristics of the people who might be affected….

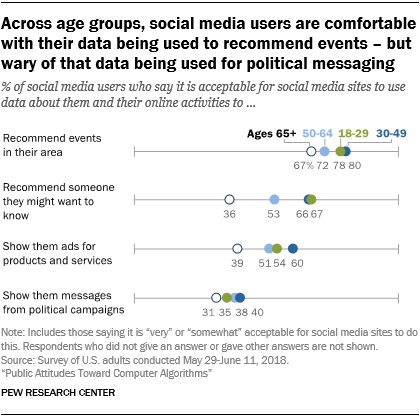

When it comes to the algorithms that underpin the social media environment, users’ comfort level with sharing their personal information also depends heavily on how and why their data are being used. A 75% majority of social media users say they would be comfortable sharing their data with those sites if it were used to recommend events they might like to attend. But that share falls to just 37% if their data are being used to deliver messages from political campaigns.

In other instances, different types of users offer divergent views about the collection and use of their personal data. For instance, about two-thirds of social media users younger than 50 find it acceptable for social media platforms to use their personal data to recommend connecting with people they might want to know. But that view is shared by fewer than half of users ages 65 and older….(More)”.

Book by Rob Reich: “Is philanthropy, by its very nature, a threat to today’s democracy? Though we may laud wealthy individuals who give away their money for society’s benefit, Just Giving shows how such generosity not only isn’t the unassailable good we think it to be but might also undermine democratic values and set back aspirations of justice. Big philanthropy is often an exercise of power, the conversion of private assets into public influence. And it is a form of power that is largely unaccountable, often perpetual, and lavishly tax-advantaged. The affluent—and their foundations—reap vast benefits even as they influence policy without accountability. And small philanthropy, or ordinary charitable giving, can be problematic as well. Charity, it turns out, does surprisingly little to provide for those in need and sometimes worsens inequality.

These outcomes are shaped by the policies that define and structure philanthropy. When, how much, and to whom people give is influenced by laws governing everything from the creation of foundations and nonprofits to generous tax exemptions for donations of money and property. Rob Reich asks: What attitude and what policies should democracies have concerning individuals who give money away for public purposes? Philanthropy currently fails democracy in many ways, but Reich argues that it can be redeemed. Differentiating between individual philanthropy and private foundations, the aims of mass giving should be the decentralization of power in the production of public goods, such as the arts, education, and science. For foundations, the goal should be what Reich terms “discovery,” or long-time-horizon innovations that enhance democratic experimentalism. Philanthropy, when properly structured, can play a crucial role in supporting a strong liberal democracy.

Just Giving investigates the ethical and political dimensions of philanthropy and considers how giving might better support democratic values and promote justice

Lorena Abad and Lucas van der Meer in information: “Stimulating non-motorized transport

For each part of the city, a score was computed based on how many common destinations (e.g., schools, universities, supermarkets, hospitals) were located within an acceptable biking distance when using only bicycle lanes and roads with low traffic stress for cyclists. Taking a weighted average of these scores resulted in an overall score for the city of Lisbon of only 8.6 out of 100 points. This shows, at a glance, that the city still has a long way to go before achieving their objectives regarding bicycle use in the city….(More)”.

Daniel Hruschka at the Conversation: “Over the last century, behavioral researchers have revealed the biases and prejudices that shape how people see the world and the carrots and sticks that influence our daily actions. Their discoveries have filled psychology textbooks and inspired generations of students. They’ve also informed how businesses manage their employees, how educators develop new curricula and how political campaigns persuade and motivate voters.

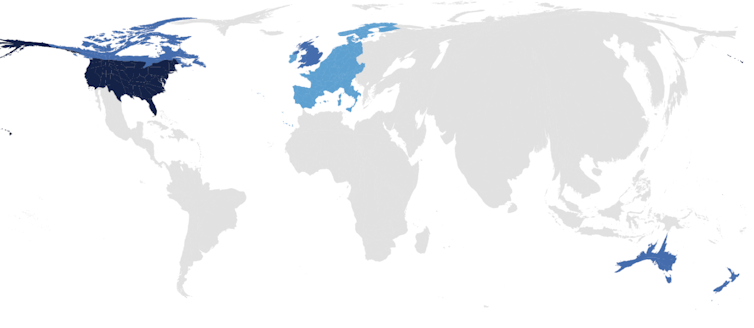

But a growing body of research has raised concerns that many of these discoveries suffer from severe biases of their own. Specifically, the vast majority of what we know about human psychology and behavior comes from studies conducted with a narrow slice of humanity – college students, middle-class respondents living near universities and highly educated residents of wealthy, industrialized and democratic nations.

To illustrate the extent of this bias, consider that more than 90 percent of studies recently published in psychological science’s flagship journal come from countries representing less than 15 percent of the world’s population.

If people thought and behaved in basically the same ways worldwide, selective attention to these typical participants would not be a problem. Unfortunately, in those rare cases where researchers have reached out to a broader range of humanity, they frequently find that the “usual suspects” most often included as participants in psychology studies are actually outliers. They stand apart from the vast majority of humanity in things like how they divvy up windfalls with strangers, how they reason about moral dilemmas and how they perceive optical illusions.

Given that these typical participants are often outliers, many scholars now describe them and the findings associated with them using the acronym WEIRD, for Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic.

WEIRD isn’t universal

Because so little research has been conducted outside this narrow set of typical participants, anthropologists like me cannot be sure how pervasive or consequential the problem is. A growing body of case studies suggests, though, that assuming such typical participants are the norm worldwide is not only scientifically suspect but can also have practical consequences….(More)”.

Book by Kevin Werbach: “The blockchain entered the world on January 3, 2009, introducing an innovative new trust architecture: an environment in which users trust a system—for example, a shared ledger of information—without necessarily trusting any of its components. The cryptocurrency Bitcoin is the most famous implementation of the blockchain, but hundreds of other companies have been founded and billions of dollars invested in similar applications since Bitcoin’s launch. Some see the blockchain as offering more opportunities for criminal behavior than benefits to society. In this book, Kevin Werbach shows how a technology resting on foundations of mutual mistrust can become trustworthy.

The blockchain, built on open software and decentralized foundations that allow anyone to participate, seems like a threat to any form of regulation. In fact, Werbach argues, law and the blockchain need each other. Blockchain systems that ignore law and governance are likely to

Report by the World Bank: “…Decisions based on data can greatly improve people’s lives. Data can uncover patterns, unexpected relationships

Data is clearly a precious commodity, and the report points out that people should have greater control over the use of their personal data. Broadly speaking, there are three possible answers to the question “Who controls our data?”: firms, governments, or users. No global consensus yet exists on the extent to which private firms that mine data about individuals should be free to use the data for profit and to improve services.

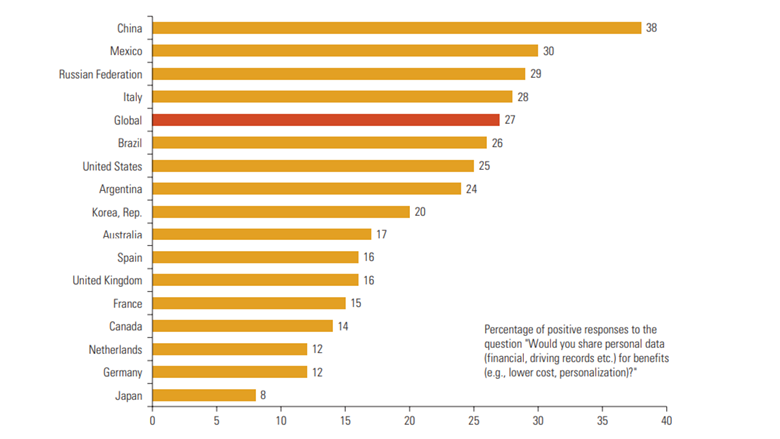

User’s willingness to share data in return for benefits and free services – such as virtually unrestricted use of social media platforms – varies widely by country. In addition to that, early internet adopters, who grew up with the internet and are now age 30–40, are the most willing to share (GfK 2017).

Are you willing to share your data? (source: GfK 2017)

On the other hand, data can worsen the digital divide – the data poor, who leave no digital trail because they have limited access, are most at risk from exclusion from services, opportunities and rights, as are those who lack a digital ID, for instance.

Firms and Data

For private sector firms, particularly those in developing countries, the report suggests how they might expand their markets and improve their competitive edge. Companies are already developing new markets and making profits by analyzing data to better understand their customers. This is transforming conventional business models. For years, telecommunications has been funded by users paying for phone calls. Today, advertisers pay for users’ data and attention are funding the internet, social media, and other platforms, such as apps, reversing the value flow.

Governments and Data

For governments and development professionals, the report provides guidance on how they might use data more creatively to help tackle key global challenges, such as eliminating extreme poverty, promoting shared prosperity, or mitigating the effects of climate change. The first step is developing appropriate guidelines for data sharing and use, and for anonymizing personal data. Governments are already beginning to use the huge quantities of data they hold to enhance service delivery, though they still have far to go to catch up with the commercial giants, the report finds.

Data for Development

The Information and Communications for Development report analyses how the data revolution is changing the behavior of governments, individuals, and firms and how these changes affect economic, social, and cultural development. This is a topic of growing importance that cannot be ignored, and the report aims to stimulate

Consultation Document by the OECD: “BASIC (Behaviour, Analysis, Strategies, Intervention, and Change) is an overarching framework for applying

The document provides an overview of the rationale, applicability and key tenets of BASIC. It walks practitioners through the five BASIC sequential stages with examples, and presents detailed ethical guidelines to be considered at each stage.

It has been developed by the OECD in partnership with

Book edited by Tom Fisher and Lorraine Gamman: “Tricky Things responds to the burgeoning of scholarly interest in the cultural meanings of objects, by addressing the moral complexity of certain designed objects and systems.

The volume brings together leading international designers, scholars and critics to explore some of the ways in which the practice of design and its outcomes can have a dark side, even when the intention is to design for the public good. Considering a range of designed objects and relationships, including guns, eyewear, assisted suicide kits, anti-rape devices, passports and prisons, the contributors offer a view of design as both progressive and problematic, able to propose new material and human relationships, yet also constrained by social norms and ideology.

This contradictory, tricky quality of design is explored in the editors’ introduction, which positions the objects, systems, services and ‘things’ discussed in the book in relation to the idea of the trickster that occurs in anthropological literature, as well as in classical thought, discussing design interventions that have positive and negative ethical consequences. These will include objects, both material and ‘immaterial’, systems with both local and global scope, and also different processes of designing.

This important new volume brings a fresh perspective to the complex nature of ‘things

Harvard Business School Case Study by Leslie K. John, Mitchell Weiss and Julia Kelley: “By the time Dan Doctoroff, CEO of Sidewalk Labs, began hosting a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” session in January 2018, he had only nine months remaining to convince the people of Toronto, their government representatives, and presumably his parent company Alphabet, Inc., that Sidewalk Labs’ plan to construct “the first truly 21st-century city” on the Canadian city’s waterfront was a sound one. Along with much excitement and optimism, strains of concern had emerged since Doctoroff and partners first announced their intentions for a city “built from the internet up” in Toronto’s Quayside district. As Doctoroff prepared for yet another milestone in a year of planning and community engagement, it was almost certain that of the many questions headed his way, digital privacy would be among them….(More)”.