Stefaan Verhulst

The Economist: “In a messy age of grinding wars and multiplying tariffs, negotiators are as busy as the stakes are high. Alliances are shifting and political leaders are adjusting—if not reversing—positions. The resulting tumult is giving even seasoned negotiators trouble keeping up with their superiors back home. Artificial-intelligence (AI) models may be able to lend a hand.

Some such models are already under development. One of the most advanced projects, dubbed Strategic Headwinds, aims to help Western diplomats in talks on Ukraine. Work began during the Biden administration in America, with officials on the White House’s National Security Council (NSC) offering guidance to the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a think-tank in Washington that runs the project. With peace talks under way, CSIS has speeded up its effort. Other outfits are doing similar work.

The CSIS programme is led by a unit called the Futures Lab. This team developed an AI language model using software from Scale AI, a firm based in San Francisco, and unique training data. The lab designed a tabletop strategy game called “Hetman’s Shadow” in which Russia, Ukraine and their allies hammer out deals. Data from 45 experts who played the game were fed into the model. So were media analyses of issues at stake in the Russia-Ukraine war, as well as answers provided by specialists to a questionnaire about the relative values of potential negotiation trade-offs. A database of 374 peace agreements and ceasefires was also poured in.

Thus was born, in late February, the first iteration of the Ukraine-Russia Peace Agreement Simulator. Users enter preferences for outcomes grouped under four rubrics: territory and sovereignty; security arrangements; justice and accountability; and economic conditions. The AI model then cranks out a draft agreement. The software also scores, on a scale of one to ten, the likelihood that each of its components would be satisfactory, negotiable or unacceptable to Russia, Ukraine, America and Europe. The model was provided to government negotiators from those last three territories, but a limited “dashboard” version of the software can be run online by interested members of the public…(More)”.

Press Release: “The Open Data Policy Lab, a collaboration between The GovLab at New York University and Microsoft, has launched the New Commons Challenge, an initiative to advance the responsible reuse of data for AI-driven solutions that enhance local decision-making and humanitarian response.

The Challenge will award two winning institutions $100,000 each to develop data commons that fuel responsible AI innovation in these critical areas.

With the increasing use of generative AI in crisis management, disaster preparedness, and local decision-making, access to diverse and high-quality data has never been more essential.

The New Commons Challenge seeks to support organizations—including start-ups, non-profits, NGOs, universities, libraries, and AI developers—to build shared data ecosystems that improve real-world outcomes, from public health to emergency response.

Bridging Research and Real-World Impact

“The New Commons Challenge is about putting data into action,” said Stefaan Verhulst, Co-Founder and Chief Research and Development Officer at The GovLab. “By enabling new models of data stewardship, we aim to support AI applications that save lives, strengthen communities, and enhance local decision-making where it matters most.”

The Challenge builds on the Open Data Policy Lab’s recent report, “Blueprint to Unlock New Data Commons for AI,” which advocates for creating collaboratively governed data ecosystems that support responsible AI development.

How the Challenge Works

The challenge unfolds in two phases: Phase One: Open Call for Concept Notes (April 14 – June 2, 2025)

Innovators world-wide are invited to submit concept notes outlining their ideas. Phase Two: Full Proposal Submissions & Expert Review (June 2025)

- Selected applicants will be invited to submit a full proposal

- An interdisciplinary panel will evaluate proposals based on their impact potential, feasibility, and ethical governance.

Winners Announced in Late Summer 2025

Two selected projects will each receive $100,000 in funding, alongside technical support, mentorship, and global recognition…(More)”.

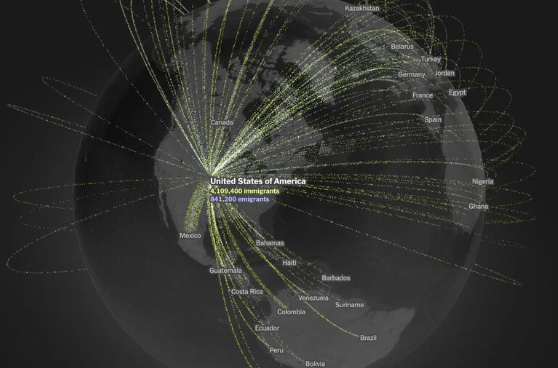

Data visualization by The New York Times: “In the maps below, Times Opinion can provide the clearest picture to date of how people move across the globe: a record of permanent migration to and from 181 countries based on a single, consistent source of information, for every month from the beginning of 2019 through the end of 2022. These estimates are drawn not from government records but from the location data of three billion anonymized Facebook users all over the world.

The analysis — the result of new research published on Wednesday from Meta, the University of Hong Kong and Harvard University — reveals migration’s true global sweep. And yes, it excludes business travelers and tourists: Only people who remain in their destination country for more than a year are counted as migrants here.

The data comes with some limitations. Migration to and from certain countries that have banned or restricted the use of Facebook, including China, Iran and Cuba, is not included in this data set, and it’s impossible to know each migrant’s legal status. Nevertheless, this is the first time that estimates of global migration flows have been made publicly available at this scale. The researchers found that from 2019 to 2022, an annual average of 30 million people — approximately one-third of a percent of the world’s population — migrated each year.

If you would like to see the data behind this analysis for yourself, we made an interactive tool that you can use to explore the full data set…(More)”

Article by Sheon Han: “Nearly 35 years ago, Ginsparg created arXiv, a digital repository where researchers could share their latest findings—before those findings had been systematically reviewed or verified. Visit arXiv.org today (it’s pronounced like “archive”) and you’ll still see its old-school Web 1.0 design, featuring a red banner and the seal of Cornell University, the platform’s institutional home. But arXiv’s unassuming facade belies the tectonic reconfiguration it set off in the scientific community. If arXiv were to stop functioning, scientists from every corner of the planet would suffer an immediate and profound disruption. “Everybody in math and physics uses it,” Scott Aaronson, a computer scientist at the University of Texas at Austin, told me. “I scan it every night.”

Every industry has certain problems universally acknowledged as broken: insurance in health care, licensing in music, standardized testing in education, tipping in the restaurant business. In academia, it’s publishing. Academic publishing is dominated by for-profit giants like Elsevier and Springer. Calling their practice a form of thuggery isn’t so much an insult as an economic observation. Imagine if a book publisher demanded that authors write books for free and, instead of employing in-house editors, relied on other authors to edit those books, also for free. And not only that: The final product was then sold at prohibitively expensive prices to ordinary readers, and institutions were forced to pay exorbitant fees for access…(More)”.

Article by Dave Lee: “Having scraped just about the entire sum of human knowledge, ChatGPT and other AI efforts are making the same rallying cry: Need input!

One solution is to create synthetic data and to train a model using that, though this comes with inherent challenges, particularly around perpetuating bias or introducing compounding inaccuracies.

The other is to find a great gushing spigot of new and fresh data, the more “human” the better. That’s where social networks come in, digital spaces where millions, even billions, of users willingly and constantly post reams of information. Photos, posts, news articles, comments — every interaction of interest to companies that are trying to build conversational and generative AI. Even better, this content is not riddled with the copyright violation risk that comes with using other sources.

Lately, top AI companies have moved more aggressively to own or harness social networks, trampling over the rights of users to dictate how their posts may be used to build these machines. Social network users have long been “the product,” as the famous saying goes. They’re now also a quasi-“product developer” through their posts.

Some companies had the benefit of a social network to begin with. Meta Platforms Inc., the biggest social networking company on the planet, used in-app notifications to inform users that it would be harnessing their posts and photos for its Llama AI models. Late last month, Elon Musk’s xAI acquired X, formerly Twitter, in what was primarily a financial sleight of hand but one that made ideal sense for Musk’s Grok AI. It has been able to gain a foothold in the chatbot market by harnessing timely tweets posted on the network as well as the huge archive of online chatter dating back almost two decades. Then there’s Microsoft Corp., which owns the professional network LinkedIn and has been pushing heavily for users (and journalists) to post more and more original content to the platform.

Microsoft doesn’t, however, share LinkedIn data with its close partner OpenAI, which may explain reports that the ChatGPT maker was in the early stages of building a social network of its own…(More)”

Article by Deborah Brown: “Expansive interagency sharing of personal data could fuel abuses against vulnerable people and communities who are already being targeted by Trump administration policies, like immigrants, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, and student protesters. The personal data held by the government reveals deeply sensitive information, such as people’s immigration status, race, gender identity, sexual orientation, and economic status.

A massive centralized government database could easily be used for a range of abusive purposes, like to discriminate against current federal employees and future job applicants on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity, or to facilitate the deportation of immigrants. It could result in people forgoing public services out of fear that their data will be weaponized against them by another federal agency.

But the danger doesn’t stop with those already in the administration’s crosshairs. The removal of barriers keeping private data siloed could allow the government or DOGE to deny federal loans for education or Medicaid benefits based on unrelated or even inaccurate data. It could also facilitate the creation of profiles containing all of the information various agencies hold on every person in the country. Such profiles, combined with social media activity, could facilitate the identification and targeting of people for political reasons, including in the context of elections.

Information silos exist for a reason. Personal data should be collected for a determined, specific, and legitimate purpose, and not used for another purpose without notice or justification, according to the key internationally recognized data protection principle, “purpose limitation.” Sharing data seamlessly across federal or even state agencies in the name of an undefined and unmeasurable goal of efficiency is incompatible with this core data protection principle…(More)”.

Paper by Francisco Mendonca, Giovanna DiMarzo, and Nabil Abdennadher: “Data cooperatives offer a new model for fair data governance, enabling individuals to collectively control, manage, and benefit from their information while adhering to cooperative principles such as democratic member control, economic participation, and community concern. This paper reviews data cooperatives, distinguishing them from models like data trusts, data commons, and data unions, and defines them based on member ownership, democratic governance, and data sovereignty. It explores applications in sectors like healthcare, agriculture, and construction. Despite their potential, data cooperatives face challenges in coordination, scalability, and member engagement, requiring innovative governance strategies, robust technical systems, and mechanisms to align member interests with cooperative goals. The paper concludes by advocating for data cooperatives as a sustainable, democratic, and ethical model for the future data economy…(More)”.

Article by Peter Buneman, Dennis Dosso, Matteo Lissandrini, Gianmaria Silvello, and He Sun: “Databases publish data. This is undoubtedly the case for scientific and statistical databases, which have largely replaced traditional reference works. Database and Web technologies have led to an explosion in the number of databases that support scientific research, for obvious reasons: Databases provide faster communication of knowledge, hold larger volumes of data, are more easily searched, and are both human- and machine-readable. Moreover, they can be developed rapidly and collaboratively by a mixture of researchers and curators. For example, more than 1,500 curated databases are relevant to molecular biology alone. The value of these databases lies not only in the data they present but also in how they organize that data.

In the case of an author or journal, most bibliometric measures are obtained from citations to an associated set of publications. There are typically many ways of decomposing a database into publications, so we might use its organization to guide our choice of decompositions. We will show that when the database has a hierarchical structure, there is a natural extension of the h-index that works on this hierarchy…(More)”.

Paper by Nicholas Biddle, Alexander Fischer, Simon D. Angus, Selen Ercan, Max Grömping, andMatthew Gray: “Global indices and media narratives indicate a decline in democratic institutions, values, and practices. Simultaneously, democratic innovators are experimenting with new ways to strengthen democracy at local and national levels. These both suggest democracies are not static; they evolve as society, technology and the environment change.

This paper examines democracy as a resilient system, emphasizing the role of applied analysis in shaping effective policy and programs, particularly in Australia. Grounded in adaptive processes, democratic resilience is the capacity of a democracy to identify problems, and collectively respond to changing conditions, balancing institutional stability with transformative. It outlines the ambition of a national network of scholars, civil society leaders, and policymakers to equip democratic innovators with practical insights and foresight underpinning new ideas. These insights are essential for strengthening both public institutions, public narratives and community programs.

We review current literature on resilient democracies and highlight a critical gap: current measurement efforts focus heavily on composite indices—especially trust—while neglecting dynamic flows and causal drivers. They focus on the descriptive features and identify weaknesses, they do not focus on the diagnostics or evidence to what strengths democracies. This is reflected in the lack of cross-sector networked, living evidence systems to track what works and why across the intersecting dynamics of democratic practices. To address this, we propose a practical agenda centred on three core strengthening flows of democratic resilience: trusted institutions, credible information, and social inclusion.

The paper reviews six key data sources and several analytic methods for continuously monitoring democratic institutions, diagnosing causal drivers, and building an adaptive evidence system to inform innovation and reform. By integrating resilience frameworks and policy analysis, we demonstrate how real-time monitoring and analysis can enable innovation, experimentation and cross-sector ingenuity.

This article presents a practical research agenda connecting a national network of scholars and civil society leaders. We suggest this agenda be problem-driven, facilitated by participatory approaches to asking and prioritising the questions that matter most. We propose a connected approach to collectively posing key questions that matter most, expanding data sources, and fostering applied ideation between communities, civil society, government, and academia—ensuring democracy remains resilient in an evolving global and national context…(More)”.

Paper by John Michael Maxel Okoche et al: “Despite significant technology advances especially in artificial intelligence (AI), crowdsourcing platforms still struggle with issues such as data overload and data quality problems, which hinder their full potential. This study addresses a critical gap in the literature how the integration of AI technologies in crowdsourcing could help overcome some these challenges. Using a systematic literature review of 77 journal papers, we identify the key limitations of current crowdsourcing platforms that included issues of quality control, scalability, bias, and privacy. Our research highlights how different forms of AI including from machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), natural language processing (NLP), automatic speech recognition (ASR), and natural language generation techniques (NLG) can address the challenges most crowdsourcing platforms face. This paper offers knowledge to support the integration of AI first by identifying types of crowdsourcing applications, their challenges and the solutions AI offers for improvement of crowdsourcing…(More)”.