Stefaan Verhulst

Book edited by Sherzod Abdukadirov: “This collection challenges the popular but abstract concept of nudging, demonstrating the real-world application of behavioral economics in policy-making and technology. Groundbreaking and practical, it considers the existing political incentives and regulatory institutions that shape the environment in which behavioral policy-making occurs, as well as alternatives to government nudges already provided by the market. The contributions discuss the use of regulations and technology to help consumers overcome their behavioral biases and make better choices, considering the ethical questions of government and market nudges and the uncertainty inherent in designing effective nudges. Four case studies – on weight loss, energy efficiency, consumer finance, and health care – put the discussion of the efficiency of nudges into concrete, recognizable terms. A must-read for researchers studying the public policy applications of behavioral economics, this book will also appeal to practicing lawmakers and regulators…(More)”

Daniele Quercia in Built Environment: “It is well known that the layout and configuration of urban space plugs directly into our sense of community wellbeing. The twentieth-century city planner Kevin Lynch showed that a city’s dwellers create their own personal ‘mental maps’ of the city based on features such as the routes they use and the areas they visit. Maps that are easy to remember and navigate bring comfort and ultimately contribute to people’s wellbeing. Unfortunately, traditional social science experiments (including those used to capture mental maps) take time, are costly, and cannot be conducted at city scale. This paper describes how, starting in mid-2012, a team of researchers from a variety of disciplines set about tackling these issues. They were able to translate a few traditional experiments into 1-minute ‘web games with a purpose’. This article describes those games, the main insights they offer, their theoretical implications for urban planning, and their practical implications for improvements in navigation technologies….(More)”

Daniel Castro at Center for Data Innovation: “Changing demographics in Europe are creating enormous challenges for the European Union (EU) and its member states. The population is getting older, putting strain on the healthcare and welfare systems. Many young people are struggling to find work as economies recover from the 2008 financial crisis. Europe is facing a swell in immigration, increasingly from war-torn Syria, and governments are finding it difficult to integrate refugees and other migrants into society.These pressures have already propelled permanent changes to the EU. This summer, a slim majority of British voters chose to leave the Union, and many of those in favor of Brexit cited immigration as a motive for their vote.

Europe needs to find solutions to these challenges. Fortunately, advances in data-driven innovation that have helped businesses boost performance can also create significant social benefits. They can support EU policy priorities for social protection and inclusion by better informing policy and program design, improving service delivery, and spurring social innovations. While some governments, nonprofit organizations, universities, and companies are using data-driven insights and technologies to support disadvantaged populations, including unemployed workers, young people, older adults, and migrants, progress has been uneven across the EU due to resource constraints, digital inequality, and restrictive data regulations. renewed European commitment to using data for social good is needed to address these challenges.

This report examines how the EU, member-states, and the private sector are using data to support social inclusion and protection. Examples include programs for employment and labor-market inclusion, youth employment and education, care for older adults, and social services for migrants and refugees. It also identifies the barriers that prevent European countries from fully capitalizing on opportunities to use data for social good. Finally, it proposes a number of actions policymakers in the EU should take to enable the public and private sectors to more effectively tackle the social challenges of a changing Europe through data-driven innovation. Policymakers should:

- Support the collection and use of relevant, timely data on the populations they seek to better serve;

- Participate in and fund cross-sector collaboration with data experts to make better use of data collected by governments and non-profit organizations working on social issues;

- Focus government research funding on data analysis of social inequalities and require grant applicants to submit plans for data use and sharing;

- Establish appropriate consent and sharing exemptions in data protection regulations for social science research; and

- Revise EU regulations to accommodate social-service organizations and their institutional partners in exploring innovative uses of data….(More)”

Linda Poon in CityLab: “Harnessing the power of open data is key to developing the smart cities of the future. But not all governments have the capacity—be that funding or human capital—to collect all the necessary information and turn it into a tool. That’s where Mapbox comes in.

Mapbox offers open-source mapping platforms, and is no stranger to turning complex data into visualizations cities can use, whether it’s mapping traffic fatalities in the U.S. or the conditions of streets in Washington, D.C., during last year’s East Coast blizzard. As part of the White House Smart Cities Initiative, which announced this week that it would make more than $80 million in tech investments this year, the company is rolling out Mapbox Cities, a new “mentorship” program that, for now, will give three cities the tools and support they need to solve some of their most pressing urban challenges. It issued a call for applications earlier this week, and responses have poured in from across the globe says Christina Franken, who specializes in smart cities at Mapbox.

“It’s very much an experimental approach to working with cities,” she says. “A lot of cities have open-data platforms but they don’t really do something with the data. So we’re trying to bridge that gap.”

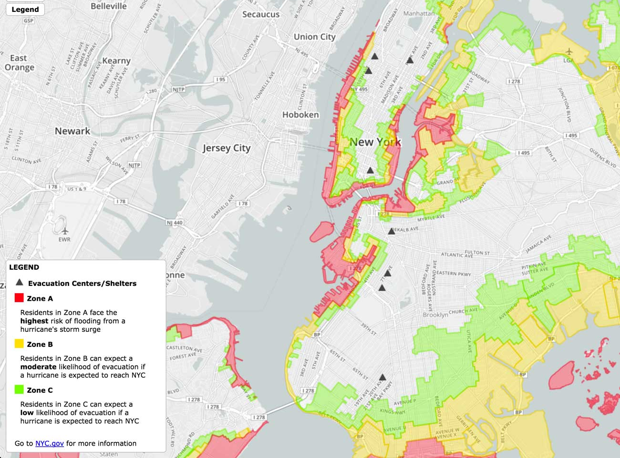

But the company isn’t approaching the project blindly. In a way, Mapbox has the necessary experience to help cities jumpstart their own projects. Its resume includes, for example, a map that visualizes the sheer quantity of traffic fatalities along any commuting route in the U.S., showcasing its ability to turn a whopping five years’ worth of data into a public-safety tool. During 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, they created a disaster-relief tool to help New Yorkers find shelter.

And that’s just in the United States. Mapbox recently also started a group focusing primarily on humanitarian issues and bringing their mapping and data-collecting tools to aid organizations all over the world in times of crisis. It provides free access to its vast collection of resources, and works closely with collaborators to help them customize maps based on specific needs….(More)”

New book edited by Rob Reich, Chiara Cordelli, and Lucy Bernholz: “Philanthropy is everywhere. In 2013, in the United States alone, some $330 billion was recorded in giving, from large donations by the wealthy all the way down to informal giving circles. We tend to think of philanthropy as unequivocally good, but as the contributors to this book show, philanthropy is also an exercise of power. And like all forms of power, especially in a democratic society, it deserves scrutiny. Yet it rarely has been given serious attention. This book fills that gap, bringing together expert philosophers, sociologists, political scientists, historians, and legal scholars to ask fundamental and pressing questions about philanthropy’s role in democratic societies.

New book edited by Rob Reich, Chiara Cordelli, and Lucy Bernholz: “Philanthropy is everywhere. In 2013, in the United States alone, some $330 billion was recorded in giving, from large donations by the wealthy all the way down to informal giving circles. We tend to think of philanthropy as unequivocally good, but as the contributors to this book show, philanthropy is also an exercise of power. And like all forms of power, especially in a democratic society, it deserves scrutiny. Yet it rarely has been given serious attention. This book fills that gap, bringing together expert philosophers, sociologists, political scientists, historians, and legal scholars to ask fundamental and pressing questions about philanthropy’s role in democratic societies.

The contributors balance empirical and normative approaches, exploring both the roles philanthropy has actually played in societies and the roles it should play. They ask a multitude of questions: When is philanthropy good or bad for democracy? How does, and should, philanthropic power interact with expectations of equal citizenship and democratic political voice? What makes the exercise of philanthropic power legitimate? What forms of private activity in the public interest should democracy promote, and what forms should it resist? Examining these and many other topics, the contributors offer a vital assessment of philanthropy at a time when its power to affect public outcomes has never been greater…(More)”

NationSwell: “…Community Solutions works in neighborhoods around the country to provide practical, data-driven solutions to the complicated problems involved in homelessness. The organization has already achieved great success: its 100,000 Homes campaign, which ran from 2010 to 2014, helped 186 participating communities house more than 105,000 homeless Americans across the country.” (Chronically homeless individuals make up 15 percent of the total homeless population, yet they utilize the majority of social services devoted towards helping them, including drop-in shelters.) To do this, it challenged the traditional approach of ending homelessness: requiring those living on the streets to demonstrate sobriety, steady income or mental health treatment, for example. Instead, it housed people first, an approach that has demonstrated overwhelming success: research finds that more than 85 percent of chronically homeless people housed through “Housing First” programs are still in homes two years later and unlikely to become homeless again.

“Technology played a critical role in the success of the 100,000 Homes campaign because it enabled multiple agencies to share and use the same data,” says Erin Connor, portfolio manager with the Cisco Foundation, which has supported Community Solutions’ technology-based initiatives. “By rigorously tracking, reporting and making decisions based on shared data, participating communities could track and monitor their progress against targets and contribute to achieving the collective goal.” As a result of this campaign, the estimated taxpayer savings was an astonishing $1.3 billion. Building on this achievement, its current Zero 2016 campaign works in 75 communities to sustainably end chronic and veteran homelessness altogether.

Technology and data gathering is critical for local and nationwide campaigns since homelessness is intimately connected to other social problems, like unemployment and poverty. One example of the local impact Community Solutions has had is in Brownsville (a neighborhood in Brooklyn, N.Y., that’s dominated by multiple public housing projects) via the Brownsville Partnership, which is demonstrating that these problems can be solved — to create “the endgame of homelessness,” as Haggerty puts it.

In Brownsville, the official unemployment rate is 16 percent, “about double that of Brooklyn” as a whole, Haggerty says, noting that the statistic excludes those not currently looking for work. In response, the organization works with existing job training programs, digging into their data and analyzing it to improve effectiveness and achieve success.

“Data is at the heart of everything we do, as far as understanding where to focus our efforts and how to improve our collective performance,” Haggerty explains. Analyzing usage data, Community Solutions works with health care providers, nonprofits, and city and state governments to figure out where the most vulnerable populations live, what systems they interact with and what help they need….(More)”

Gina Lucarelli, Tom Saunders and Eddie Copeland at Nesta: “The mountain kingdom of Lesotho, a small landlocked country in Sub-Saharan Africa, is an unlikely place to look for healthcare innovation. Yet in 2016, it became the first country in Africa to deploy the test and treat strategy for treating people with HIV. Rather than waiting for white blood cell counts to drop, patients begin treatment as soon as they are diagnosed. This strategy is backed by the WHO as it has the potential to increase the number of people who are able to access treatment, consequently reducing transmisssion and keeping people with HIV healthy and alive for longer.

While lots of good work is underway in Lesotho, and billions have been spent on HIV programmes in the country, the percentage of the population infected with HIV has remained steady and is now almost 23%. Challenges of this scale need new ideas and better ways to adopt them.

On a recent trip to Lesotho as part of a project with the United Nations Development Group, we met various UN agencies, the World Bank, government leaders, civil society actors and local businesses, to learn about the key development issues in Lesotho and to discuss the role that ‘collective intelligence’ might play in creating better country development plans. The key question Nesta and the UN are working on is: how can we increase the impact of the UN’s work by tapping into the ideas, information and possible solutions which are distributed among many partners, the private sector, and the 2 million people of Lesotho?

…our framework of collective intelligence, a set of iterative stages which can help organisations like the UN tap into the ideas, information and possible solutions of groups and individuals which are not normally involved included in the problem solving process. For each stage, we also presented a number of examples of how this works in practice.

Collective intelligence framework – stages and examples

-

Better understanding the facts, data and experiences: New tools, from smartphones to online communities enable researchers, practitioners and policymakers to collect much larger amounts of data much more quickly. Organisations can use this data to target their resources at the most critical issues as well as feed into the development of products and services that more accurately meet the needs of citizens. Examples include mPower, a clinical study which used an app to collect data about people with Parkinsons disease via surveys and smartphone sensors.

-

Better development of options and ideas: Beyond data collection, organisations can use digital tools to tap into the collective brainpower of citizens to come up with better ideas and options for action. Examples include participatory budgeting platforms like “Madame Mayor, I have an idea” and challenge prizes, such as USAID’s Ebola grand challenge.

-

Better, more inclusive decision making: Decision making and problem solving are usually left to experts, yet citizens are often best placed to make the decisions that will affect them. New digital tools make it easier than ever for governments to involve citizens in policymaking, planning and budgeting. Our D-CENT tools enable citizen involvement in decision making in a number of fields. Another example is the Open Medicine Project, which designs digital tools for healthcare in consultation with both practitioners and patients.

-

Better oversight and improvement of what is done: From monitoring corruption to scrutinising budgets, a number of tools allow broad involvement in the oversight of public sector activity, potentially increasing accountability and transparency. The Family and Friends Test is a tool that allows NHS users in the UK to submit feedback on services they have experienced. So far, 25 million pieces of feedback have been submitted. This feedback can be used to stimulate local improvement and empower staff to carry out changes… (More)”

“The U.S. Data Federation will support government-wide data standardization and data federation initiatives across both Federal agencies and local governments. This is intended to be a fundamental coordinating mechanism for a more open and interconnected digital government by profiling and supporting use-cases that demonstrate unified and coherent data architectures across disparate government agencies. These examples will highlight emerging data standards and API initiatives across all levels of government, convey the level of maturity for each effort, and facilitate greater participation by government agencies. Initiatives that may be profiled within the U.S. Data Federation include Open311, DOT’s National Transit Map, the Project Open Data metadata schema, Contact USA, and the Police Data Initiative. As part of the U.S. Data Federation, GSA will also pilot the development of reusable components needed for a successful data federation strategy including schema documentation tools, schema validation tools, and automated data aggregation and normalization capabilities. The U.S. Data Federation will provide more sophisticated and seamless opportunities on the foundation of U.S. open data initiatives by allowing the public to more easily do comparative data analysis across government bodies and create applications that work across multiple government agencies….(More)”

Sally McGrane at the NewYorker: “When Leo Tolstoy’s great-great-granddaughter, the journalist Fyokla Tolstaya, announced that the Leo Tolstoy State Museum was looking for volunteers to proofread some forty-six thousand eight hundred pages of her relative’s writings, she hoped to generate enough interest to get the first round of corrections done in six months.

Within days, some three thousand Russians—engineers, I.T. workers, schoolteachers, retirees, a student pilot, a twenty-year-old waitress—signed on. “We were so happy and so surprised,” said Tolstaya. “They finished in fourteen days.”

Now, thanks largely to the efforts of these volunteers, nearly all of the great Russian writer’s massive body of work, including novels, diaries, letters, religious tracts, philosophical treatises, travelogues, and childhood memories, will soon be available online, in a form that can be easily downloaded, free of charge. “Of course we realized there are some novels on the Internet,” Tolstaya said. “But most [writings] are not. We in the museum decided this is not good.”…

The definitive, ninety-volume jubilee edition of Tolstoy’s works, compiled and published in Russia from the nineteen-twenties to the nineteen-fifties, had already been scanned by the Russian State Library. However, converting the PDFs into an easy-to-use digital format posed a challenge. For one thing, even after ABBYY, a company that specializes in translating printed documents into digital records, offered their services for free, proofreading costs were likely to be prohibitive. Charging readers to download the works was not an option. “At the end of his life, Tolstoy said, ‘I don’t need any money for my work. I want to give my work to the people,’ “ said Tolstaya. “It was important for us to make it free for everyone. It is his will.”

That was when they hit on the idea of crowdsourcing, Tolstaya said. “It’s according to Leo Tolstoy’s ideas, to do it with the help of all people around the world—vsem mirom—even the world’s hardest task can be done with the help of everyone.”…(More)”

Call for Evidence from The British Academy and the Royal Society: “…The project seeks to make recommendations for cross-sectoral governance arrangements that can ensure the UK remains a world leader in this area. The project will draw on scholars and scientists from across disciplines and will look at current and historical case studies of data governance, and of broader technology governance, from a range of countries and sectors. It will seek to enable connected debate by creating common frameworks to move debates on data governance forward.

Background

It is essential to get the best possible environment for the safe and rapid use of data in order to enhance UK’s wellbeing, security and economic growth. The UK has world class academic expertise in data science, in ethics and aspects other of governance; and it has a rapidly growing tech sector and there is a real opportunity for the UK to lead internationally in creating insights and mechanisms for enabling the new data sciences to benefit society.

While there are substantial arrangements in place for the safe use of data in the UK, these inevitably were designed early in the days of information technology and tend to rest on outdated notions of privacy and consent. In addition, newer considerations such as statistical stereotyping and bias in datasets, and implications for the freedom of choice, autonomy and equality of opportunity of individuals, come to the fore in this new technological context, as do transparency, accountability and openness of decision making.

Terms of Reference

The project seeks to:

- Identify the communities with interests in the governance of data and its uses, but which may be considering these issues in different contexts and with varied aims and assumptions, in order to facilitate dialogue between these communities. These include academia, industry and the public sector.

- Clarify where there are connections between different debates, identifying shared issues and common questions, and help to develop a common framework and shared language for debate.

- Identify which social, ethical and governance challenges arise in the context of developments in data use.

- Set out the public interests at stake in governance of data and its uses, and the relationships between them, and how the principles of responsible research and innovation (RRI) apply in the context of data use.

- Make proposals for the UK to establish a sustained and flexible platform for debating issues of data governance, developing consensus about future legal and technical frameworks, and ensuring that learning and good practice spreads as fast as possible….(More)”