Christian Seelos & Johanna Mair at Stanford Social Innovation Review: “Efforts by social enterprises to develop novel interventions receive a great deal of attention. Yet these organizations often stumble when it comes to turning innovation into impact. As a result, they fail to achieve their full potential. Here’s a guide to diagnosing and preventing several “pathologies” that underlie this failure….

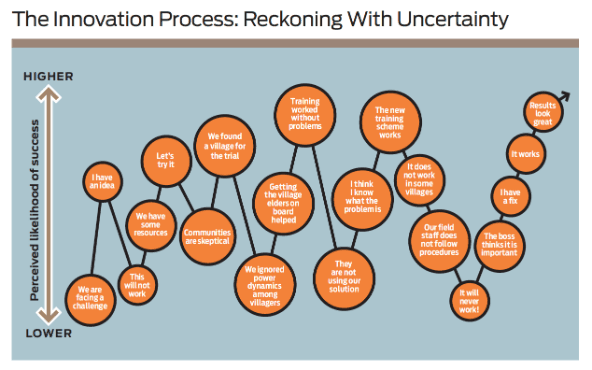

The core purpose of an innovation process is the conversion of uncertainty into knowledge. Or to put it another way: Innovation is essentially a matter of learning. In fact, one critical insight that we have drawn from our research is that effective organizations approach innovation not with an expectation of success but with an expectation of learning. Innovators who expect success from innovation efforts will inevitably encounter disappointment, and the experience of failure will generate a blame culture in their organization that dramatically lowers their chance of achieving positive impact. But a focus on learning creates a sense of progress rather than a sense of failure. The high-impact organizations that we have studied owe much of their success to their wealth of accumulated knowledge—knowledge that often has emerged from failed innovation efforts.

Innovation uncertainty has multiple dimensions, and organizations need to be vigilant about addressing uncertainty in all of its forms. (See “Types of Innovation Uncertainty” below.) Let’s take a close look at three aspects of the innovation process that often involve a considerable degree of uncertainty.

Problem formulation | Organizations may incorrectly frame the problem that they aim to solve, and identifying that problem accurately may require several iterations and learning cycles…

Solution development | Even when an organization has an adequate understanding of a problem, it may not be able to access and deploy the resources needed to create an effective and robust solution….

Alignment with identity | Innovation may lead an organization in a direction that does not fit its culture or its sense of its purpose—its sense of “who we are.”…

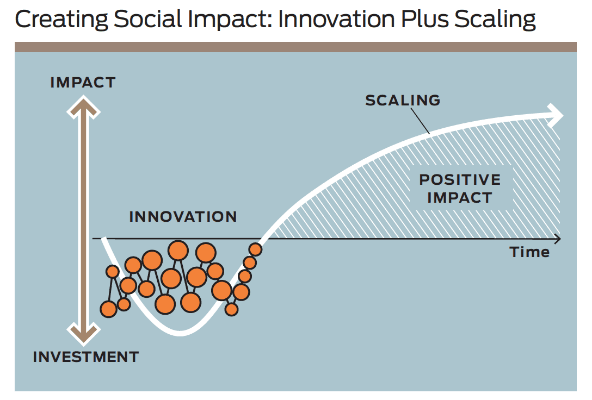

In short, innovation plus scaling equals impact. Innovation is an investment of resources that creates a new potential; scaling creates impact by enacting that potential. Because innovation creates only the potential for impact, we advocate replacing the assumption that “innovation is good, and more is better” with a more critical view: Innovation, we argue, needs to prove itself on the basis of the impact that it actually creates. The goal is not innovation for its own sake but productive innovation.

Productive innovation depends on two factors: (1) an organization’s capacity for efficiently replacing innovation uncertainty with knowledge, and (2) its ability to scale up innovation outcomes by enhancing its organizational effectiveness. Innovation and scaling thus work together to form an overall social impact creation process. Over time, an investment in innovation—in the work of overcoming uncertainty—yields positive social impact, and the value of such impact will eventually exceed the cost of that investment. But that will be the case only if an organization is able to master the scaling part of this process….

Focusing on Pathologies

Through our study of social enterprises, we have devised a set of six pathologies—six ways that organizations limit their capacity for productive innovation. From the stage when people first develop (or fail to develop) the idea for an innovation to the stage when scaling efforts take off (or fail to take off), these pathologies adversely affect an organization’s ability to make its way through the social impact creation process. (See “Creating Social Impact: Six Innovation Pathologies to Avoid” below.) Organizations can greatly improve the impact of their innovation efforts by working to prevent or treat these pathologies.

Never getting started | In too many cases, organizations simply fail to invest seriously in the work of innovation. This pathology has many causes. People in organizations may have neither the time nor the incentive to develop or communicate new ideas. Or they may find that their ideas fall on deaf ears. Or they may have a tendency to discuss an idea endlessly—until the problem that gave rise to it has been replaced by another urgent problem or until an opportunity has vanished….

Pursuing too many bad ideas | Organizations in the social sector frequently fall into the habit of embracing a wide variety of ideas for innovation without regard to whether those ideas are sound. The recent obsession with “scientific” evaluation tools such as randomized controlled trials, or RCTs, exemplifies this tendency to favor costly ideas that may or may not deliver real benefits. As with other pathologies, many factors potentially contribute to this one. Funders may push their favorite solutions regardless of how well they understand the problems that those solutions target or how well a solution fits a particular organization. Or an organization may fail to invest in learning about the context of a problem before adopting a solution. Wasting scarce resources on the pursuit of bad ideas creates frustration and cynicism within an organization. It also increases innovation uncertainty and the likelihood of failure….

Stopping too early | In some instances, organizations are unable or unwilling to devote adequate resources to the development of worthy ideas. When resources are scarce and not formally dedicated to innovation processes, project managers will struggle to develop an idea and may have to abandon it prematurely. Too often, they end up taking the blame for failure, and others in their organization ignore the adverse circumstances that caused it. Decision makers then reallocate resources on an ad-hoc basis to other urgent problems or to projects that seem more important. As a result, even promising innovation efforts come to a grinding halt….

Stopping too late | Even more costly than stopping too early is stopping too late. In this pathology, an organization continues an innovation project even after the innovation proves to be ineffective or unworkable. This problem occurs, for example, when an unsuccessful innovation happens to be the pet project of a senior leader who has limited experience. Leaders who have recently joined an organization and who are keen to leave their mark rather than continue what their predecessor has built are particularly likely to engage in this pathology. Another cause of “stopping too late” is the assumption that a project budget needs to be spent. The consequences of this pathology are clear: Organizations expend scarce resources with little hope for success and without gaining any useful knowledge….

Scaling too little | To repeat an essential point that we made earlier: no scaling, no impact. This pathology—which involves a failure to move beyond the initial stages of developing, launching, and testing an intervention—is all too common in the social enterprise field. Thousands of inspired young people want to become social entrepreneurs. But few of them are willing or able to build an organization that can deliver solutions at scale. Too many organizations, therefore, remain small and lack the resources and capabilities required for translating innovation into impact….

Innovating again too soon | Too many organizations rush to launch new innovation projects instead of investing in efforts to scale interventions that they have already developed. The causes of this pathology are fairly well known: People often portray scaling as dull, routine work and innovation as its more attractive sibling. “Innovative” proposals thus attract funders more readily than proposals that focus on scaling. Reinforcing this bias is the preference among many funders for “lean projects” that reduce overhead costs to a minimum. These factors lead organizations to jump opportunistically from one innovation grant to another….(More)”