Eric B. Steiner at Wired: “A few weeks ago, I asked the internet to guess how many coins were in a huge jar…The mathematical theory behind this kind of estimation game is apparently sound. That is, the mean of all the estimates will be uncannily close to the actual value, every time. James Surowiecki’s best-selling book, Wisdom of the Crowd, banks on this principle, and details several striking anecdotes of crowd accuracy. The most famous is a 1906 competition in Plymouth, England to guess the weight of an ox. As reported by Sir Francis Galton in a letter to Nature, no one guessed the actual weight of the ox, but the average of all 787 submitted guesses was exactly the beast’s actual weight….

So what happened to the collective intelligence supposedly buried in our disparate ignorance?

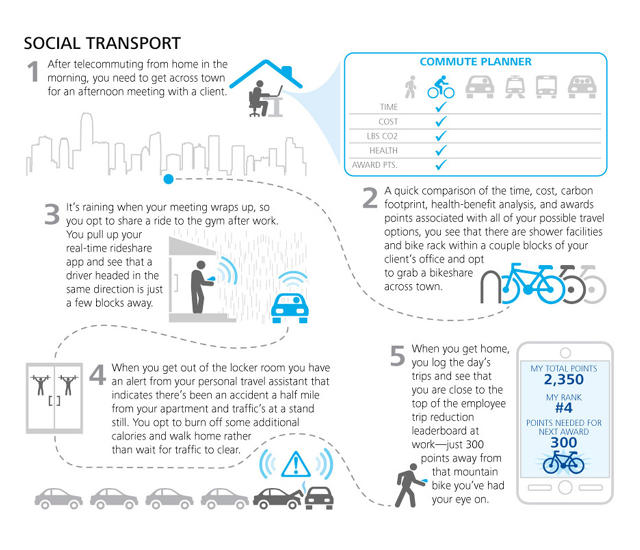

Most successful crowdsourcing projects are essentially the sum of many small parts: efficiently harvested resources (information, effort, money) courtesy of a large group of contributors. Think Wikipedia, Google search results, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, and KickStarter.

But a sum of parts does not wisdom make. When we try to produce collective intelligence, things get messy. Whether we are predicting the outcome of an election, betting on sporting contests, or estimating the value of coins in a jar, the crowd’s take is vulnerable to at least three major factors: skill, diversity, and independence.

A certain amount of skill or knowledge in the crowd is obviously required, while crowd diversity expands the number of possible solutions or strategies. Participant independence is important because it preserves the value of individual contributors, which is another way of saying that if everyone copies their neighbor’s guess, the data are doomed.

Failure to meet any one of these conditions can lead to wildly inaccurate answers, information echo, or herd-like behavior. (There is more than a little irony with the herding hazard: The internet makes it possible to measure crowd wisdom and maybe put it to use. Yet because people tend to base their opinions on the opinions of others, the internet ends up amplifying the social conformity effect, thereby preventing an accurate picture of what the crowd actually thinks.)

What’s more, even when these conditions—skill, diversity, independence—are reasonably satisfied, as they were in the coin jar experiment, humans exhibit a whole host of other cognitive biases and irrational thinking that can impede crowd wisdom. True, some bias can be positive; all that Gladwellian snap-judgment stuff. But most biases aren’t so helpful, and can too easily lead us to ignore evidence, overestimate probabilities, and see patterns where there are none. These biases are not vanquished simply by expanding sample size. On the contrary, they get magnified.

Given the last 60 years of research in cognitive psychology, I submit that Galton’s results with the ox weight data were outrageously lucky, and that the same is true of other instances of seemingly perfect “bean jar”-styled experiments….”