Stefaan Verhulst

Article by Duncan C. McElfresh: “Say you run a hospital and you want to estimate which patients have the highest risk of deterioration so that your staff can prioritize their care1. You create a spreadsheet in which there is a row for each patient, and columns for relevant attributes, such as age or blood-oxygen level. The final column records whether the person deteriorated during their stay. You can then fit a mathematical model to these data to estimate an incoming patient’s deterioration risk. This is a classic example of tabular machine learning, a technique that uses tables of data to make inferences. This usually involves developing — and training — a bespoke model for each task. Writing in Nature, Hollmann et al.report a model that can perform tabular machine learning on any data set without being trained specifically to do so.

Tabular machine learning shares a rich history with statistics and data science. Its methods are foundational to modern artificial intelligence (AI) systems, including large language models (LLMs), and its influence cannot be overstated. Indeed, many online experiences are shaped by tabular machine-learning models, which recommend products, generate advertisements and moderate social-media content3. Essential industries such as healthcare and finance are also steadily, if cautiously, moving towards increasing their use of AI.

Despite the field’s maturity, Hollmann and colleagues’ advance could be revolutionary. The authors’ contribution is known as a foundation model, which is a general-purpose model that can be used in a range of settings. You might already have encountered foundation models, perhaps unknowingly, through AI tools, such as ChatGPT and Stable Diffusion. These models enable a single tool to offer varied capabilities, including text translation and image generation. So what does a foundation model for tabular machine learning look like?

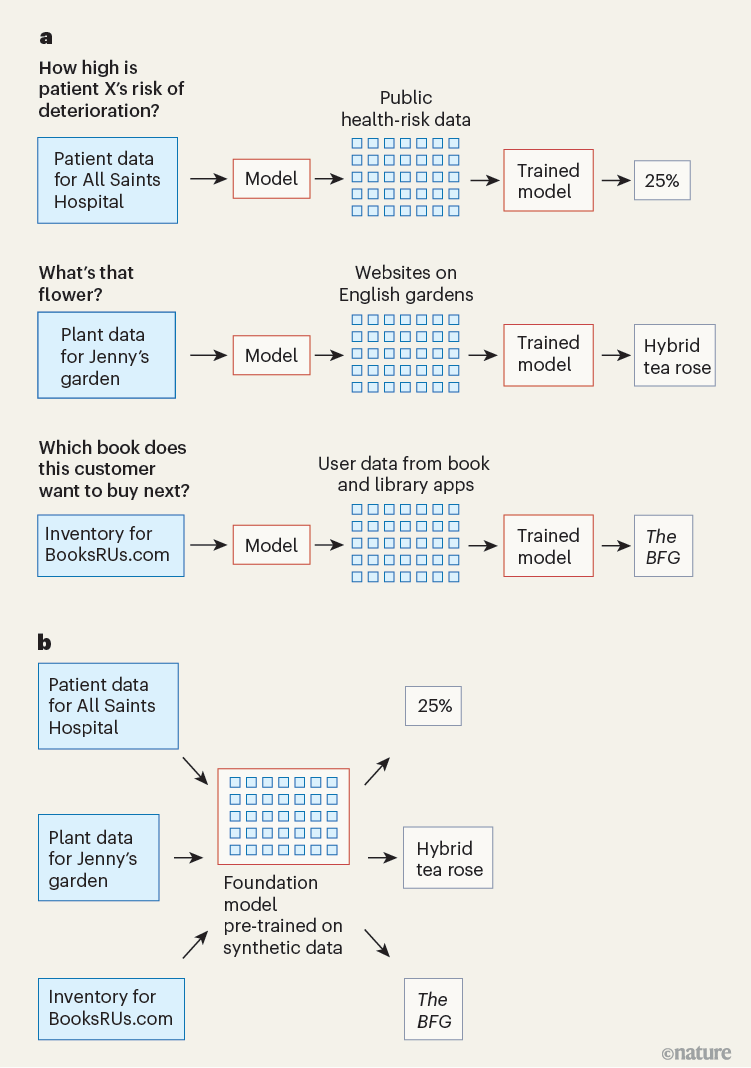

Let’s return to the hospital example. With spreadsheet in hand, you choose a machine-learning model (such as a neural network) and train the model with your data, using an algorithm that adjusts the model’s parameters to optimize its predictive performance (Fig. 1a). Typically, you would train several such models before selecting one to use — a labour-intensive process that requires considerable time and expertise. And of course, this process must be repeated for each unique task.

Editorial to Special Issue by Cristina Poncibò and Martin Ebers: “Large language models (LLMs) represent one of the most significant technological advancements in recent decades, offering transformative capabilities in natural language processing and content generation. Their development has far-reaching implications across technological, economic and societal domains, simultaneously creating opportunities for innovation and posing profound challenges for governance and regulation. As LLMs become integral to various sectors, from education to healthcare to entertainment, regulators are scrambling to establish frameworks that ensure their safe and ethical use.

Our issue primarily examines the private ordering, regulatory responses and normative frameworks for LLMs from a comparative law perspective, with a particular focus on the European Union (EU), the United States (US) and China. An introductory part preliminarily explores the technical principles that underpin LLMs as well as their epistemological foundations. It also addresses key sector-specific legal challenges posed by LLMs, including their implications for criminal law, data protection and copyright law…(More)”.

Report by the World Economic Forum: “Technological change, geoeconomic fragmentation, economic uncertainty, demographic shifts and the green transition – individually and in combination are among the major drivers expected to shape and transform the global labour market by 2030. The Future of Jobs Report 2025 brings together the perspective of over 1,000 leading global employers—collectively representing more than 14 million workers across 22 industry clusters and 55 economies from around the world—to examine how these macrotrends impact jobs and skills, and the workforce transformation strategies employers plan to embark on in response, across the 2025 to 2030 timeframe…(More)”.

About: “What if generative AI could help us understand people with opposing views better just by showing how they use common words and phrases differently? That’s the deceptively simple-sounding idea behind a new experiment from MIT’s Center for Constructive Communication (CCC).

It’s called the Bridging Dictionary (BD), a research prototype that’s still very much a work in progress – one we hope your feedback will help us improve.

The Bridging Dictionary identifies words and phrases that both reflect and contribute to sharply divergent views in our fractured public sphere. That’s the “dictionary” part. If that’s all it did, we could just call it the “Frictionary.” But the large language model (LLM) that undergirds the BD also suggests less polarized alternatives – hence “bridging.”

In this prototype, research scientist Doug Beeferman and a team at CCC led by Maya Detwiller and Dennis Jen used thousands of transcripts and opinion articles from foxnews.com and msnbc.com as proxies for the conversation on the right and the left. You’ll see the most polarized words and phrases when you sample the BD for yourself, but you can also plug any term of your choosing into the search box. (For a more complete explanation of the methodology behind the BD, see https://bridgingdictionary.org/info/ .)…(More)”.

About: “The People Say is an online research hub that features first-hand insights from older adults and caregivers on the issues most important to them, as well as feedback from experts on policies affecting older adults.

This project particularly focuses on the experiences of communities often under-consulted in policymaking, including older adults of color, those who are low income, and/or those who live in rural areas where healthcare isn’t easily accessible. The People Say is funded by The SCAN Foundation and developed by researchers and designers at the Public Policy Lab.

We believe that effective policymaking listens to most-affected communities—but policies and systems that serve older adults are typically formed with little to no input from older adults themselves. We hope The People Say will help policymakers hear the voices of older adults when shaping policy…(More)”

Article by Kshemendra Paul: “It’s time to strengthen the use of data, evidence and transparency to stop driving with mud on the windshield and to steer the government toward improving management of its programs and operations.

Existing Government Accountability Office and agency inspectors general reports identify thousands of specific evidence-based recommendations to improve efficiency, economy and effectiveness, and reduce fraud, waste and abuse. Many of these recommendations aim at program design and requirements, highlighting specific instances of overlap, redundancy and duplication. Others describe inadequate internal controls to balance program integrity with the experience of the customer, contractor or grantee. While progress is being reported in part due to stronger partnerships with IGs, much remains to be done. Indeed, GAO’s 2023 High Risk List, which it has produced going back to 1990, shows surprisingly slow progress of efforts to reduce risk to government programs and operations.

Here are a few examples:

- GAO estimates recent annual fraud of between $233 billion to $521 billion, or about 3% to 7% of federal spending. On the other hand, identified fraud with high-risk Recovery Act spending was held under 1% using data, transparency and partnerships with Offices of Inspectors General.

- GAO and IGs have collectively identified hundreds of billions in potential cost savings or improvements not yet addressed by federal agencies.

- GAO has recently described shortcomings with the government’s efforts to build evidence. While federal policymakers need good information to inform their decisions, the Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking previously said, “too little evidence is produced to meet this need.”

One of the main reasons for agency sluggishness is the lack of agency and governmentwide use of synchronized, authoritative and shared data to support how the government manages itself.

For example, the Energy Department IG found that, “[t]he department often lacks the data necessary to make critical decisions, evaluate and effectively manage risks, or gain visibility into program results.” It is past time for the government to commit itself to move away from its widespread use of data calls, the error-prone, costly and manual aggregation of data used to support policy analysis and decision-making. Efforts to embrace data-informed approaches to manage government programs and operations are stymied by lack of basic agency and governmentwide data hygiene. While bright pockets exist, management gaps, as DOE OIG stated, “create blind spots in the universe of data that, if captured, could be used to more efficiently identify, track and respond to risks…”

The proposed approach starts with current agency operating models, then drives into management process integration to tackle root causes of dysfunction from the bottom up. It recognizes that inefficiency, fraud and other challenges are diffused, deeply embedded and have non-obvious interrelationships within the federal complex…(More)”

Paper by Timothy Fraser, Daniel P. Aldrich, Andrew Small and Andrew Littlejohn: “When disaster strikes, urban planners often rely on feedback and guidance from committees of officials, residents, and interest groups when crafting reconstruction policy. Focusing on recovery planning committees after Japan’s 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disasters, we compile and analyze a dataset on committee membership patterns across 39 committees with 657 members. Using descriptive statistics and social network analysis, we examine 1) how community representation through membership varied among committees, and 2) in what ways did committees share members, interlinking members from certain interests groups. This study finds that community representation varies considerably among committees, negatively related to the prevalence of experts, bureaucrats, and business interests. Committee membership overlap occurred heavily along geographic boundaries, bridged by engineers and government officials. Engineers and government bureaucrats also tend to be connected to more members of the committee network than community representatives, giving them prized positions to disseminate ideas about best practices in recovery. This study underscores the importance of diversity and community representation in disaster recovery planning to facilitate equal participation, information access, and policy implementation across communities…(More)”.

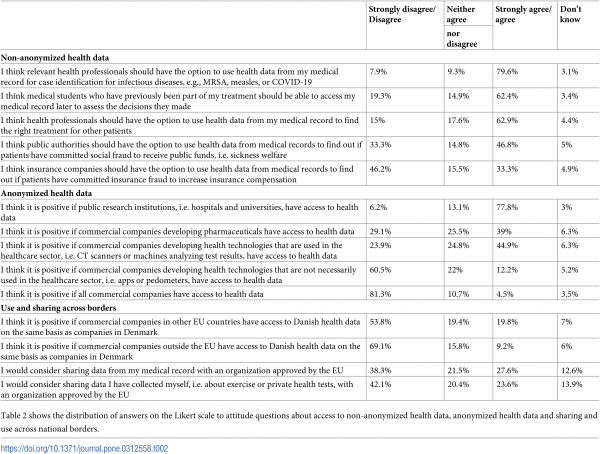

Paper by Lea Skovgaard et al: “Everyday clinical care generates vast amounts of digital data. A broad range of actors are interested in reusing these data for various purposes. Such reuse of health data could support medical research, healthcare planning, technological innovation, and lead to increased financial revenue. Yet, reuse also raises questions about what data subjects think about the use of health data for various different purposes. Based on a survey with 1071 respondents conducted in 2021 in Denmark, this article explores attitudes to health data reuse. Denmark is renowned for its advanced integration of data infrastructures, facilitating data reuse. This is therefore a relevant setting from which to explore public attitudes to reuse, both as authorities around the globe are currently working to facilitate data reuse opportunities, and in the light of the recent agreement on the establishment in 2024 of the European Health Data Space (EHDS) within the European Union (EU). Our study suggests that there are certain forms of health data reuse—namely transnational data sharing, commercial involvement, and use of data as national economic assets—which risk undermining public support for health data reuse. However, some of the purposes that the EHDS is supposed to facilitate are these three controversial purposes. Failure to address these public concerns could well challenge the long-term legitimacy and sustainability of the data infrastructures currently under construction…(More)”

Paper by Isabel James: “Despite the global proliferation of ocean governance frameworks that feature socioeconomic variables, the inclusion of community needs and local ecological knowledge remains underrepresented. Participatory mapping or Participatory GIS (PGIS) has emerged as a vital method to address this gap by engaging communities that are conventionally excluded from ocean planning and marine conservation. Originally developed for forest management and Indigenous land reclamation, the scholarship on PGIS remains predominantly focused on terrestrial landscapes. This review explores recent research that employs the method in the marine realm, detailing common methodologies, data types and applications in governance and conservation. A typology of ocean-centered PGIS studies was identified, comprising three main categories: fisheries, habitat classification and blue economy activities. Marine Protected Area (MPA) design and conflict management are the most prevalent conservation applications of PGIS. Case studies also demonstrate the method’s effectiveness in identifying critical marine habitats such as fish spawning grounds and monitoring endangered megafauna. Participatory mapping shows particular promise in resource and data limited contexts due to its ability to generate large quantities of relatively reliable, quick and low-cost data. Validation steps, including satellite imagery and ground-truthing, suggest encouraging accuracy of PGIS data, despite potential limitations related to human error and spatial resolution. This review concludes that participatory mapping not only enriches scientific research but also fosters trust and cooperation among stakeholders, ultimately contributing to more resilient and equitable ocean governance…(More)”.

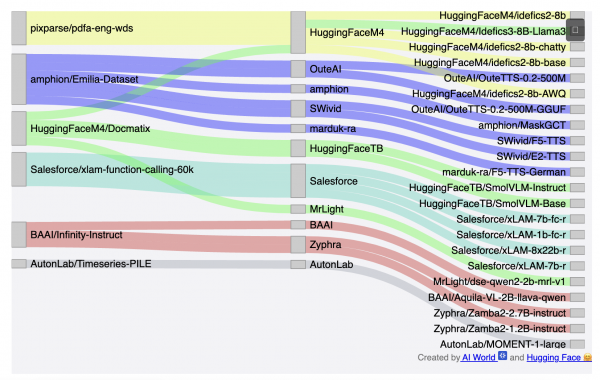

A Sankey diagram developed by AI World and Hugging Face:”… illustrating the flow from top open-source datasets through AI organizations to their derivative models, showcasing the collaborative nature of AI development…(More)”.