Stefaan Verhulst

Paper by Margaret Hughes, et al: “Communities frequently report sending feedback “into a void” during community engagement processes like neighborhood planning, creating a critical disconnect between public input and decision-making. Voice to Vision addresses this gap with a sociotechnical system that comprises three integrated components: a flexible data architecture linking community input to planning outputs, a sensemaking interface for planners to analyze and synthesize feedback, and a community-facing platform that makes the entire engagement process transparent. By creating a shared information space between stakeholders, our system demonstrates how structured data and specialized interfaces can foster cooperation across stakeholder groups, while addressing tensions in accessibility and trust formation. Our CSCW demonstration will showcase this system’s ability to transform opaque civic decision-making processes into collaborative exchanges, inviting feedback on its potential applications beyond urban planning…(More)”.

Book by Maximilian Kasy: “AI is inescapable, from its mundane uses online to its increasingly consequential decision-making in courtrooms, job interviews, and wars. The ubiquity of AI is so great that it might produce public resignation—a sense that the technology is our shared fate.

As economist Maximilian Kasy shows in The Means of Prediction, artificial intelligence, far from being an unstoppable force, is irrevocably shaped by human decisions—choices made to date by the ownership class that steers its development and deployment. Kasy shows that the technology of AI is ultimately not that complex. It is insidious, however, in its capacity to steer results to its owners’ wants and ends. Kasy clearly and accessibly explains the fundamental principles on which AI works, and, in doing so, reveals that the real conflict isn’t between humans and machines, but between those who control the machines and the rest of us.

The Means of Prediction offers a powerful vision of the future of AI: a future not shaped by technology, but by the technology’s owners. Amid a deluge of debates about technical details, new possibilities, and social problems, Kasy cuts to the core issue: Who controls AI’s objectives, and how is this control maintained? The answer lies in what he calls “the means of prediction,” or the essential resources required for building AI systems: data, computing power, expertise, and energy. As Kasy shows, in a world already defined by inequality, one of humanity’s most consequential technologies has been and will be steered by those already in power.

Against those stakes, Kasy offers an elegant framework both for understanding AI’s capabilities and for designing its public control. He makes a compelling case for democratic control over AI objectives as the answer to mounting concerns about AI’s risks and harms. The Means of Prediction is a revelation, both an expert undressing of a technology that has masqueraded as more complicated and a compelling call for public oversight of this transformative technology…(More)”.

Paper by Rosa Vicari: “…Misinformation significantly challenges disaster risk management by increasing risks and complicating response efforts. This technical note introduces a methodology toolbox designed to help policy makers, decision makers, practitioners, and scientists systematically assess, prevent, and mitigate the risks and impacts of misinformation in disaster scenarios. The methodology consists of eight steps, each offering specific tools and strategies to help address misinformation effectively. The process begins with defining the communication context using PESTEL analysis and Berlo’s communication model to assess external factors and information flow. It then focuses on identifying misinformation patterns through data collection and analysis using advanced AI methods. The impact of misinformation on risk perceptions is assessed through established theoretical frameworks, guiding the development of targeted strategies. The methodology includes practical measures for mitigating misinformation, such as implementing AI tools for prebunking and debunking false information. Evaluating the effectiveness of these measures is crucial, and continuous monitoring is recommended to adapt strategies in real-time. Ethical considerations are outlined to ensure compliance with international laws and data privacy regulations. The final step emphasizes managerial aspects, including clear communication and public education, to build trust and promote reliable information sources. This structured approach provides practical insights for enhancing disaster response and reducing the risks associated with misinformation…(More)”.

Article by Victor Dominello: “Every form tells a story. It reveals how government sees itself, how it interacts with people, and who really holds the power.

When you fill out a form on paper, online, or through an app, you’re not just providing information. You’re entering a contract of trust. You’re revealing how much the system values your time, your data, and your dignity.

Forms are not paperwork. They’re the DNA of government. They show who controls the data. They show how much friction citizens face in accessing basic services. And as forms have evolved, so too has government, from paper-based bureaucracy to intelligent, anticipatory systems.

Government 0.0: The paper-form era

Before 1990, everything started with paper. Licences, registrations, applications: all handwritten, stamped, and filed away.

In my early years as a lawyer, I remember attending property settlements with clients clutching paper certificates of title and mortgage documents. They waited their turn in long queues at government offices. Every transaction required physical signatures, physical stamps, and physical handovers…Now we stand on the threshold of Government 4.0: the form-less age.

This is the era of mainstream AI agents. Intelligent systems that talk to each other, share verified data securely, and act on our behalf.

In this world, humans never see a form.

A birth automatically triggers relevant services. A job loss activates training and income support. A licence renewal happens invisibly in the background.

Forward-looking nations are already designing for this future. They’re building systems where services become proactive and anticipatory…(More)”.

Article by Steve MacFeely: “On 1 May 2025, the United Nations (UN) Commission for Science and Technology for Development (CSTD) held the first meeting of a new Multi-Stakeholder Working Group on Data Governance at All Levels in Geneva. Less than three weeks later, the UN Statistics Commission held the first (online) meeting of their new Working Group on Data Governance. Only a fortnight later, on 8 June 2025, the UNESCO Broadband Commission launched their new Data Governance Toolkit at the World Summit on the Information Society (tinyurl.com/fcnzu4ha).

What triggered this flurry of data governance activity at the UN? This article sets out some of the key events and work that led up to this eruption of activity and attempts to explain why it is important…(More)”.

Paper by Shusei Hayashi, Takahiro Yabe, and Naoya Fujiwara: “Recent social media data analysis suggests that children from low-income families are more likely to exceed their parents’ income if exposed to interactions with high-income individuals. This highlights the potential of understanding parental behavior to break the cycle of poverty. Using detailed human mobility data, this study estimated the movements of parents with young children, extracted by focusing on drop-off activities in childcare facilities. The differences between parents and non-parents were analyzed with respect to time spent at home, visiting tendencies, and frequency of visits to various locations. It was shown that parents raising children spend significantly more time at home and explored new locations less frequently than non-parents. Budget-conscious dining patterns were also observed, with parents visiting establishments such as restaurants and bars less frequently while frequenting supermarkets and fast food outlets more. Additionally, parents operated within a smaller activity radius. These findings provide a foundation for understanding parental social interactions and offer insights for improving urban support policies for low-income families, contributing to data-driven approaches to social inclusion…(More)”.

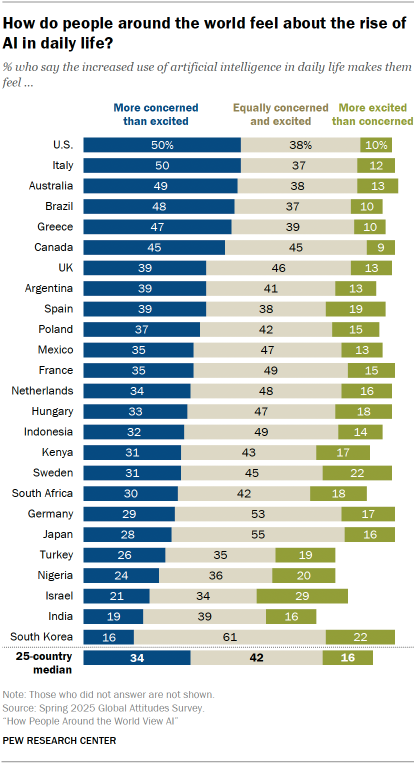

Pew Research: “As the use of artificial intelligence (AI) increases rapidly, most people across 25 countries surveyed say they have heard or read at least a little about the technology.

And on balance, people are more concerned than excited about its growing presence in daily life.

A median of 34% of adults across these countries have heard or read a lot about AI, while 47% have heard a little and 14% say they’ve heard nothing at all, according to a spring 2025 Pew Research Center survey.

But many are worried about AI’s effects on daily life. A median of 34% of adults say they are more concerned than excited about the increased use of AI, while 42% are equally concerned and excited. A median of 16% are more excited than concerned…

Concerns about AI are especially common in the United States, Italy, Australia, Brazil and Greece, where about half of adults say they are more concerned than excited. But as few as 16% in South Korea are mainly concerned about the prospect of AI in their lives.

In fact, in many countries surveyed, a larger share of people are equally excited and concerned about the growing use of AI. In no country surveyed do more than three-in-ten adults say they are mainly excited.

The survey also finds a strong correlation between a country’s income – as measured by gross domestic product per capita – and awareness of AI. People in higher-income nations tend to have heard more about AI than those in less wealthy economies. For example, around half of adults in the comparatively wealthy countries of Japan, Germany, France and the U.S. have heard a lot about AI, but only 14% in India and 12% in Kenya say the same.

Trust in government to regulate AI

The survey also asked whether people trust their own country, the European Union, the U.S. and China to regulate the use of AI effectively.

Most people trust their own country to regulate AI. This includes 89% of adults in India, 74% in Indonesia and 72% in Israel. At the other end of the spectrum, only 22% of Greeks trust their country to regulate AI effectively.

Americans are almost evenly divided between trust in their country to regulate AI (44%) and distrust (47%)…(More)”.

Paper by Luisa Kruse and Max von Grafenstein: “The European data strategy aims to make the EU a leader in a data-driven world. To this aim, the EU is creating a single market for data where 1) data can flow across sectors for the benefit of all; 2) European laws like data protection and competition law are fully respected; and 3) the rules for access and use of data are fair, practical and clear. In order to structure the corresponding initiatives of legislators and public authorities, it is important to clarify the data ownership models on which the initiatives are based: Proprietary data models, open data models or so-called data commons models. Based on a literature analysis, this article first provides an overview of the discussed economic and social advantages and disadvantages of proprietary and open data models and, against this background, clarifies the concept of the data commons. In doing so, this article understands the data commons concept to mean that everyone has an equal right in principle to exploit the value of data and control its associated risks. Based on this understanding, purely technical power of the data holder to exclude others from “her” data does not mean that she has a superior or even exclusive right to generate value from the data. By means of legal mechanisms, the competent legislator or public authorities may therefore counteract such purely de facto powers of data holders by opening their technical access control over data for other parties and define the conditions of its use. In doing so, the interests of the data holder in keeping the data for themselves must be weighed up against the interests of data users in using the data as well as the interests in controlling the related risks of all parties affected by this use. While this balancing exercise may be established, in a more or less general manner, by the European or national legislator or even by municipalities, data intermediaries will have to play a central role in ensuring that this balancing of interest is resolved in specific cases. Data intermediaries may do this not only by specifying the general data usage rules provided by the legislators and municipalities in the form of context-specific access and use conditions but above all by monitoring compliance with these conditions…(More)”.

Essay by Stefaan G. Verhulst: “Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) has given millions of people something extraordinary: a way to move forward from a tabula rasa. The once-intimidating blank page — whether in writing, coding, designing, or imagining — no longer induces paralysis. With a few keystrokes, ideas flow, drafts appear, and tasks that once demanded hours of toil now unfold in seconds. Never before has human creativity been so efficiently scaffolded.

Yet this newfound fluency comes at a cost. In outsourcing the burden of beginnings, we risk dulling the more subtle and essential capacity of inquiry — the art of asking good questions. As generative systems like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude proliferate, they seem to provide answers for everything. But these systems, for all their prowess, only ever respond to prompts, and they do not provide intentions or understandings behind their replies. They do not think; they predict. What appears as insight is, in fact, the statistical sequencing of tokens — the next likely word rather than a considered idea. In short, generative AI simulates reasoning without ever engaging in it.

All of this means that the value of the work generated by these remarkable systems continue to depend critically on the quality of the questions we ask–the prompts we pose, and the nudges we offer to coax alternative statistical pathways. We are, in short, increasingly living in an era that is answer rich, yet questions poor. The risk is that we overlook this, in the process losing our critical — and deeply human — capacity to ask the questions that truly matter…(More)”.

Article by Dane Gambrell: “On a sweltering August afternoon in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, technologist Chris Whong(opens in new window) led a small group of researchers, students, and local community members on an unusual walking tour. We weren’t visiting the neighborhood’s trendy restaurants or thrift shops. Instead, we were hunting for overlooked public spaces: pocket parks(opens in new window), street plazas, and other spaces that many New Yorkers walk past without even realizing they’re open to the public.

Our map for this expedition was a new app called NYC Public Space(opens in new window). Whong, a former public servant in NYC’s Department of City Planning, built the platform using generative AI tools to write code he didn’t know how to write himself – a practice often called “vibe coding(opens in new window).” The result is a searchable dataset and map of roughly 2,800 public spaces across New York City, from massive green spaces like Flushing Meadows–Corona Park to tiny triangular plazas you’ve probably never noticed.

New York City has no shortage(opens in new window) of places to sit, relax, or eat lunch outside. The city’s public realm includes more than 2,000 parks, hundreds of street plazas, playgrounds, and waterfront areas, as well as roughly 600 privately owned public spaces (POPS) created by developers in exchange for zoning benefits.

What it lacks is an easy way for people to discover these spaces. Some public spaces appear on Google Maps or Apple Maps, but many don’t. Even when they do, it’s often unclear what amenities they offer and whether they’re actually publicly accessible. You might walk by a building in your neighborhood every day but have no idea that it contains a courtyard or indoor plaza open to the public…(More)”