Stefaan Verhulst

Lorena Abad and Lucas van der Meer in information: “Stimulating non-motorized transport

For each part of the city, a score was computed based on how many common destinations (e.g., schools, universities, supermarkets, hospitals) were located within an acceptable biking distance when using only bicycle lanes and roads with low traffic stress for cyclists. Taking a weighted average of these scores resulted in an overall score for the city of Lisbon of only 8.6 out of 100 points. This shows, at a glance, that the city still has a long way to go before achieving their objectives regarding bicycle use in the city….(More)”.

Daniel Hruschka at the Conversation: “Over the last century, behavioral researchers have revealed the biases and prejudices that shape how people see the world and the carrots and sticks that influence our daily actions. Their discoveries have filled psychology textbooks and inspired generations of students. They’ve also informed how businesses manage their employees, how educators develop new curricula and how political campaigns persuade and motivate voters.

But a growing body of research has raised concerns that many of these discoveries suffer from severe biases of their own. Specifically, the vast majority of what we know about human psychology and behavior comes from studies conducted with a narrow slice of humanity – college students, middle-class respondents living near universities and highly educated residents of wealthy, industrialized and democratic nations.

To illustrate the extent of this bias, consider that more than 90 percent of studies recently published in psychological science’s flagship journal come from countries representing less than 15 percent of the world’s population.

If people thought and behaved in basically the same ways worldwide, selective attention to these typical participants would not be a problem. Unfortunately, in those rare cases where researchers have reached out to a broader range of humanity, they frequently find that the “usual suspects” most often included as participants in psychology studies are actually outliers. They stand apart from the vast majority of humanity in things like how they divvy up windfalls with strangers, how they reason about moral dilemmas and how they perceive optical illusions.

Given that these typical participants are often outliers, many scholars now describe them and the findings associated with them using the acronym WEIRD, for Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic.

WEIRD isn’t universal

Because so little research has been conducted outside this narrow set of typical participants, anthropologists like me cannot be sure how pervasive or consequential the problem is. A growing body of case studies suggests, though, that assuming such typical participants are the norm worldwide is not only scientifically suspect but can also have practical consequences….(More)”.

Book by Kevin Werbach: “The blockchain entered the world on January 3, 2009, introducing an innovative new trust architecture: an environment in which users trust a system—for example, a shared ledger of information—without necessarily trusting any of its components. The cryptocurrency Bitcoin is the most famous implementation of the blockchain, but hundreds of other companies have been founded and billions of dollars invested in similar applications since Bitcoin’s launch. Some see the blockchain as offering more opportunities for criminal behavior than benefits to society. In this book, Kevin Werbach shows how a technology resting on foundations of mutual mistrust can become trustworthy.

The blockchain, built on open software and decentralized foundations that allow anyone to participate, seems like a threat to any form of regulation. In fact, Werbach argues, law and the blockchain need each other. Blockchain systems that ignore law and governance are likely to

Report by the World Bank: “…Decisions based on data can greatly improve people’s lives. Data can uncover patterns, unexpected relationships

Data is clearly a precious commodity, and the report points out that people should have greater control over the use of their personal data. Broadly speaking, there are three possible answers to the question “Who controls our data?”: firms, governments, or users. No global consensus yet exists on the extent to which private firms that mine data about individuals should be free to use the data for profit and to improve services.

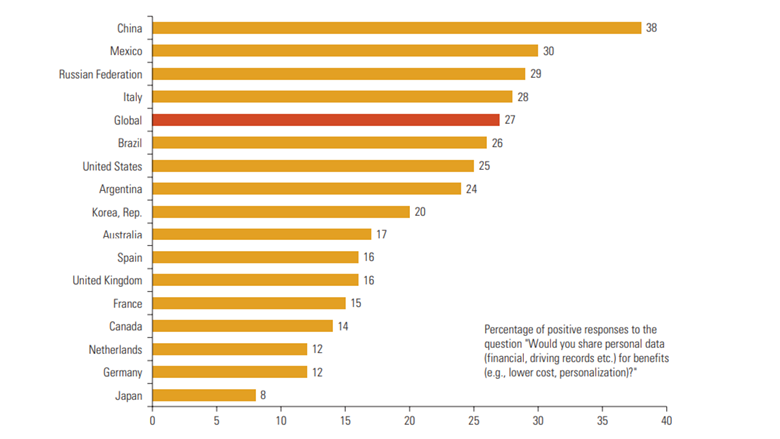

User’s willingness to share data in return for benefits and free services – such as virtually unrestricted use of social media platforms – varies widely by country. In addition to that, early internet adopters, who grew up with the internet and are now age 30–40, are the most willing to share (GfK 2017).

Are you willing to share your data? (source: GfK 2017)

On the other hand, data can worsen the digital divide – the data poor, who leave no digital trail because they have limited access, are most at risk from exclusion from services, opportunities and rights, as are those who lack a digital ID, for instance.

Firms and Data

For private sector firms, particularly those in developing countries, the report suggests how they might expand their markets and improve their competitive edge. Companies are already developing new markets and making profits by analyzing data to better understand their customers. This is transforming conventional business models. For years, telecommunications has been funded by users paying for phone calls. Today, advertisers pay for users’ data and attention are funding the internet, social media, and other platforms, such as apps, reversing the value flow.

Governments and Data

For governments and development professionals, the report provides guidance on how they might use data more creatively to help tackle key global challenges, such as eliminating extreme poverty, promoting shared prosperity, or mitigating the effects of climate change. The first step is developing appropriate guidelines for data sharing and use, and for anonymizing personal data. Governments are already beginning to use the huge quantities of data they hold to enhance service delivery, though they still have far to go to catch up with the commercial giants, the report finds.

Data for Development

The Information and Communications for Development report analyses how the data revolution is changing the behavior of governments, individuals, and firms and how these changes affect economic, social, and cultural development. This is a topic of growing importance that cannot be ignored, and the report aims to stimulate

Consultation Document by the OECD: “BASIC (Behaviour, Analysis, Strategies, Intervention, and Change) is an overarching framework for applying

The document provides an overview of the rationale, applicability and key tenets of BASIC. It walks practitioners through the five BASIC sequential stages with examples, and presents detailed ethical guidelines to be considered at each stage.

It has been developed by the OECD in partnership with

Book edited by Tom Fisher and Lorraine Gamman: “Tricky Things responds to the burgeoning of scholarly interest in the cultural meanings of objects, by addressing the moral complexity of certain designed objects and systems.

The volume brings together leading international designers, scholars and critics to explore some of the ways in which the practice of design and its outcomes can have a dark side, even when the intention is to design for the public good. Considering a range of designed objects and relationships, including guns, eyewear, assisted suicide kits, anti-rape devices, passports and prisons, the contributors offer a view of design as both progressive and problematic, able to propose new material and human relationships, yet also constrained by social norms and ideology.

This contradictory, tricky quality of design is explored in the editors’ introduction, which positions the objects, systems, services and ‘things’ discussed in the book in relation to the idea of the trickster that occurs in anthropological literature, as well as in classical thought, discussing design interventions that have positive and negative ethical consequences. These will include objects, both material and ‘immaterial’, systems with both local and global scope, and also different processes of designing.

This important new volume brings a fresh perspective to the complex nature of ‘things

Harvard Business School Case Study by Leslie K. John, Mitchell Weiss and Julia Kelley: “By the time Dan Doctoroff, CEO of Sidewalk Labs, began hosting a Reddit “Ask Me Anything” session in January 2018, he had only nine months remaining to convince the people of Toronto, their government representatives, and presumably his parent company Alphabet, Inc., that Sidewalk Labs’ plan to construct “the first truly 21st-century city” on the Canadian city’s waterfront was a sound one. Along with much excitement and optimism, strains of concern had emerged since Doctoroff and partners first announced their intentions for a city “built from the internet up” in Toronto’s Quayside district. As Doctoroff prepared for yet another milestone in a year of planning and community engagement, it was almost certain that of the many questions headed his way, digital privacy would be among them….(More)”.

Mapping by Kate Gasporro: “…The field of civic technology is relatively new. There are limited strategies to measure

By mapping the landscape of civic technology, we can see more clearly how eParticipation is being used to address public service challenges, including infrastructure delivery. Although many scholars and practitioners have created independent categories for eParticipation, these categorization frameworks follow a similar pattern. At one end of the spectrum, eParticipation efforts provide public service information and relevant updates to citizens or allowing citizens to contact their officials in a unidirectional flow of information. At the other end, eParticipation efforts allow for deliberate democracy where citizens share decision-making with local government officials. Of the dozen categorization frameworks we found, we selected the most comprehensive one accepted by practitioners. This framework draws from public participation practices and identifies five categories:

eInforming : One-way communication providing online information to citizens (in the form of a website) or togovernment (via ePetitions)eConsulting : Limited two-way communication where citizens can voice their opinions and provide feedbackeInvolving : Two-way communication where citizens go through an online process to capture public concernseCollaborating : Enhanced two-way communication that allows citizens to develop alternative solutions and identify the preferred solution, but decision making remains the government’s responsibilityeEmpowerment : Advanced two-way communication that allows citizens to influence and make decisions as co-producers of policies…

After surveying the civic technology space, we found 24 tools that use eParticipation for infrastructure delivery. We map these technologies according to their intended use phase in infrastructure delivery and type of

The field of civic technology is relatively new. There are limited strategies to measure

Karl Manheim and Lyric Kaplan at Yale Journal of Law and Technology: “A “Democracy Index” is published annually by the Economist. For 2017, it reported that half of the world’s countries scored lower than the previous year. This included the United States, which was demoted from “full democracy” to “flawed democracy.” The principal factor was “erosion of confidence in government and public institutions.” Interference by Russia and voter manipulation by Cambridge Analytica in the 2016 presidential election played a large part in that public disaffection.

Threats of these kinds will continue, fueled by growing deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to manipulate the preconditions and levers of democracy. Equally destructive is AI’s threat to decisional andinforma-tional privacy. AI is the engine behind Big Data Analytics and the Internet of Things. While conferring some consumer benefit, their principal function at present is to capture personal information, create detailed behavioral profiles and sell us goods and agendas. Privacy, anonymity and autonomy are the main casualties of AI’s ability to manipulate choices in economic and political decisions.

The way forward requires greater attention to these risks at the nation-al

Keith N. Hampton and Barry Wellman in Contemporary Sociology:”Why does every generation believe that relationships were stronger and community better in the recent past? Lamenting about the loss of community, based on a selective perception of the present and an idealization of ‘‘traditional community,’’ dims awareness of powerful inequalities and cleavages that have always pervaded human society and favors deterministic models over a nuanced understanding of how network affordances contribute to different outcomes. The beˆtes noirs have varied according to the moral panic of the times: industrialization, bureaucratization, urbanization, capitalism, socialism, and technological developments have all been tabbed by such diverse commentators as Thomas Jefferson (1784), Karl Marx (1852), Louis Wirth (1938), Maurice Stein (1960), Robert Bellah et al. (1996), and Tom Brokaw (1998). Each time, observers look back nostalgically to what they supposed were the supportive, solidary communities of the previous generation. Since the advent of the internet, the moral panicers have seized on this technology as the latest cause of lost community, pointing with alarm to what digital technologies are doing to relationships. As the focus shifts to social media and mobile devices, the panic seems particularly acute….

Taylor Dotson’s (2017) recent book Technically Together has a broader timeline for the demise of community. He sees it as happen- ing around the time the internet was popularized, with community even worse off as a result of Facebook and mobile devices. Dotson not only blames new technologies for the decline of community, but social theory, specifically the theory and the practice of ‘‘networked individualism’’: the relational turn from bounded, densely knit local groups to multiple, partial, often far-flung social networks (Rainie and Wellman 2012). Dotson takes the admirable position that social science should do more to imagine different outcomes, new technological possibilities that can be created by tossing aside the trends of today and engineering social change through design….

Some alarm in the recognition that the nature of community is changing as technologies change is sensible, and we have no quarrel with the collective desire to have better, more supportive friends, families, and communities. As Dotson implies, the maneuverability in having one’s own individually networked community can come at the cost of local group solidarity. Indeed, we have also taken action that does more than pontificate to promote local community, building community on and offline (Hampton 2011).

Yet part of contemporary unease comes from a selective perception of the present and an idealization of other forms of community. There is nostalgia for a perfect form of community that never was. Longing for a time when the grass was ever greener dims an awareness of the powerful stresses and cleavages that have always pervaded human society. And advocates, such as Dotson (2017), who suggest the need to save a particular type of community at the expense of another, often do so blind of the potential tradeoffs….(More)”