Paper by Wolff, Annika; Kortuem, Gerd and Cavero, Jose: “A bottom-up approach to smart cities places citizens in an active role of contributing, analysing and interpreting data in pursuit of tackling local urban challenges and building a more sustainable future city. This vision can only be realised if citizens have sufficient data literacy skills and experience of large, complex, messy, ever expanding data sets. Schools typically focus on teaching data handling skills using small, personally collected data sets obtained through scientific experimentation, leading to a gap between what is being taught and what will be needed as big data and analytics become more prevalent. This paper proposes an approach to teaching data literacy in the context of urban innovation tasks, using an idea of Urban Data Games. These are supported by a set of training data and resources that will be used in school trials for exploring the problems people have when dealing with large data and trialling novel approaches for teaching data literacy….(More)”

A sentiment analysis of U.S. local government tweets: The connection between tone and citizen involvement

Paper by Staci M. Zavattaro, P. Edward French, and Somya D. Mohanty: “As social media tools become more popular at all levels of government, more research is needed to determine how the platforms can be used to create meaningful citizen–government collaboration. Many entities use the tools in one-way, push manners. The aim of this research is to determine if sentiment (tone) can positively influence citizen participation with government via social media. Using a systematic random sample of 125 U.S. cities, we found that positive sentiment is more likely to engender digital participation but this was not a perfect one-to-one relationship. Some cities that had an overall positive sentiment score and displayed a participatory style of social media use did not have positive citizen sentiment scores. We argue that positive tone is only one part of a successful social media interaction plan, and encourage social media managers to actively manage platforms to use activities that spur participation….(More)”

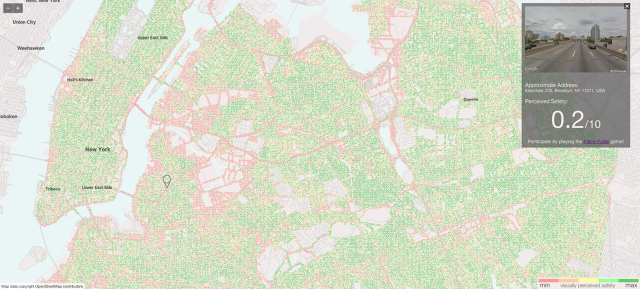

How Crowdsourcing And Machine Learning Will Change The Way We Design Cities

Now, that data is being used to predict what parts of cities feel the safest. StreetScore, a collaboration between the MIT Media Lab’s Macro Connections and Camera Culture groups, uses an algorithm to create a super high-resolution map of urban perceptions. The algorithmically generated data could one day be used to research the connection between urban perception and crime, as well as informing urban design decisions.

The algorithm, created by Nikhil Naik, a Ph.D. student in the Camera Culture lab, breaks an image down into its composite features—such as building texture, colors, and shapes. Based on how Place Pulse volunteers rated similar features, the algorithm assigns the streetscape a perceived safety score between 1 and 10. These scores are visualized as geographic points on a map, designed by MIT rising sophomore Jade Philipoom. Each image available from Google Maps in the two cities are represented by a colored dot: red for the locations that the algorithm tags as unsafe, and dark green for those that appear safest. The site, now limited to New York and Boston, will be expanded to feature Chicago and Detroit later this month, and eventually, with data collected from a new version of Place Pulse, will feature dozens of cities around the world….(More)”

Bloomberg Philanthropies Launches $42 Million “What Works Cities” Initiative

Press Release: “Today, Bloomberg Philanthropies announced the launch of the What Works Cities initiative, a $42 million program to help 100 mid-sized cities better use data and evidence. What Works Cities is the latest initiative from Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Government Innovation portfolio which promotes public sector innovation and spreads effective ideas amongst cities.

Through partners, Bloomberg Philanthropies will help mayors and local leaders use data and evidence to engage the public, make government more effective and improve people’s lives. U.S. cities with populations between 100,000 and 1 million people are invited to apply.

“While cities are working to meet new challenges with limited resources, they have access to more data than ever – and they are increasingly using it to improve people’s lives,” said Michael R. Bloomberg. “We’ll help them build on their progress, and help even more cities take steps to put data to work. What works? That’s a question that every city leader should ask – and we want to help them find answers.”

The $42 million dollar effort is the nation’s most comprehensive philanthropic initiative to help accelerate the ability of local leaders to use data and evidence to improve the lives of their residents. What Works Cities will provide mayors with robust technical assistance, expertise, and peer-to-peer learning opportunities that will help them enhance their use of data and evidence to improve services to solve problems for communities. The program will help cities:

1. Create sustainable open data programs and policies that promote transparency and robust citizen engagement;

2. Better incorporate data into budget, operational, and policy decision making;

3. Conduct low-cost, rapid evaluations that allow cities to continually improve programs; and

4. Focus funding on approaches that deliver results for citizens.

Across the initiative, Bloomberg Philanthropies will document how cities currently use data and evidence in decision making, and how this unique program of support helps them advance. Over time, the initiative will also launch a benchmark system which will collect standardized, comparable data so that cities can understand their performance relative to peers.

In cities across the country, mayors are increasingly relying on data and evidence to deliver better results for city residents. For example, New Orleans’ City Hall used data to reduce blighted residences by 10,000 and increased the number of homes brought into compliance by 62% in 2 years. The City’s “BlightStat” program has put New Orleans, once behind in efforts to revitalize abandoned and decaying properties, at the forefront of national efforts.

In New York City and other jurisdictions, open data from transit agencies has led to the creation of hundreds of apps that residents now use to get around town, choose where to live based on commuting times, provide key transit information to the visually impaired, and more. And Louisville has asked volunteers to attach GPS trackers to their asthma inhalers to see where they have the hardest time breathing. The city is now using that data to better target the sources of air pollution….

To learn more and apply to be a What Works City, visitwww.WhatWorksCities.org.”

Innovating for Impact in Public Policy

Post by Derek B. Miller and Lisa Rudnick: “Political systems across democratic countries are becoming more ideologically and politically divided over how to use increasingly limited resources. In the face of these pressures everyone wants results: they want them cheap and they want them now. This demand for better results is falling squarely on civil servants.

In the performance of their jobs, everyone is being asked to do more with less. This demand comes independent of theme, scope, or size of the public institution. It is as true for those working in transportation as it is for those in education or public health or international peace and security; whether in local government or at UN agencies; or else in the NGOs, think tanks, and community-based organizations that partner with them. Even private industry feels the squeeze.

When we say “do more with less” we mean more impact, better results, and more effective outcomes than ever before with less money and time, fewer people, and (often) less political support.

In taking a cue from the private sector, the public sector is looking for solutions in “Innovation.”

Innovation is the act of making possible that which was previously impossible in order to solve a problem. Given that present performance is insufficient to meet demand, there is a turn to innovation (broadly defined) to maximize resources through new methods to achieve goals. In this way, innovation is being treated as a strategic imperative for successful governance.

From our vantage point — having worked on innovation and public policy for over a decade, mostly from within the UN — we see two driving forces for innovation that we believe are going to shape the future of public policy performance and, by extension, the character of democratic governance in the years to come. Managing the convergence of these two approaches to innovation is going to be one of the most important public policy agendas for the next several decades (for a detailed discussion of this topic, see Trying it on for Size: Design and International Public Policy).

The first is evidence-based policymaking. The goal of evidence-based policymaking is to build a base of evidence — often about past performance — so that lessons can be learned, best practices distilled, and new courses of action recommended (or required) to guide future organizational behavior for more efficient or effective outcomes.

The second force is going to be design. The field of design evolved in the crucible of the arts and not in the Academy. It is therefore a late-comer to public policy…(More)”

Rebooting Democracy

, , and at Foreign Policy: “….The next generation of political and economic systems may look very different from the ones we know today.

Some changes along these lines are already happening. Civil society groups, cities, organizations, and government agencies have begun to experiment with a host of innovations that promote decentralization, redundancy, inclusion, and diversity. These include participatory budgeting, where residents of a city democratically choose how public monies are spent. They also include local currency systems, open-source development, open-design, open-data and open-government, public banking, “buy local” campaigns, crowdfunding, and socially responsible business models.

Such innovations are a type of churning on the edges of current systems. But in complex systems, changes at the periphery can cascade to changes at the core. Further, the speed of change is increasing. Consider the telephone, first introduced by Bell in 1876. It took about 75 years to reach adoption by 50 percent of the market. A century later the Internet did the same in about 35 years. We can expect that the next major innovations will be adopted even faster.

Following the examples of the telephone and Internet, it appears likely that the technology of new economic and political decision-making systems will first be adopted by small groups, then spread virally. Indeed, small groups, such as neighborhoods and cities, are among today’s leaders in innovation. The influence of larger bodies, such as big corporations and non-governmental organizations, is also growing steadily as nation states increasingly share their powers, willingly or not.

Changes are evident even within large corporations. Open-source software development has become the norm, for example, and companies as large as Toyota have announced plans to freely share their intellectual property.

While these innovations represent potentially important parts of new political and economic systems, they are only the tip of the iceberg. Systems engineering design could eventually integrate these and other innovations into efficient, user-friendly, scalable, and resilient whole systems. But the need for this kind of innovation is not yet universally acknowledged. In its list of 14 grand challenges for the 21st century, the U.S. National Academy of Engineering addresses many of the problems caused by poor decision making, such as climate change, but not the decision-making systems themselves. The work has only just begun.

…

The development of new options will dramatically alter how democracy is used, adjusted, and exported. Attention will shift toward groups, perhaps at the city/regional level, who wish to apply the flexible tools freely available on the Internet. Future practitioners of democracy will invest more time and resources to understand what communities want and need — helping them adapt designs to make them fit for their purpose — and to build networked systems that beneficially connect diverse groups into larger political and economic structures. In time, when the updates to next-generation political and economic near completion, we might find ourselves more fully embracing the notion “engage local, think global.”…(More)

Knight Cities Challenge Winners

Carol Coletta at Knight Foundation: “32 civic innovators receive $5 million in funding in first Knight Cities Challenge…

Several themes emerged among the winning applications, which all sought to accelerate talent, opportunity or engagement—the three primary drivers of city success—in some way. “Bringing life back to public and vacant space” was the theme of our largest category of winners, representing almost a third of the group. The second largest category was “changing the stories people tell about their cities” with almost 20 percent. Three more themes each represented 13 percent of the winning ideas: “reimagining the civic commons,” “retaining talent” and “promoting civic engagement.” A full list of the winners appears below…. (More)”

Can Big Data Measure Livability in Cities?

PlaceILive: “Big data helps us measure and predict consumer behavior, hurricanes and even pregnancies. It has revolutionized the way we access and use information. That being said, so far big data has not been able to tackle bigger issues like urbanization or improve the livability of cities.

A new startup, www.placeilive.com thinks big data should and can be used to measure livability. They aggregated open data from government institutions and social media to create a tool that can calculate just that. ….PlaceILive wants to help people and governments better understand their cities, so that they can make smarter decisions. Cities can be more sustainable, while its users save money and time when they are choosing a new home.

Not everyone is eager to read long lists of raw data. Therefore they created appealing user-friendly maps that visualize the statistics. Offering the user fast and accessible information on the neighborhoods that matter to them.

Another cornerstone of PlaceILive is their Life Quality Index: an algorithm that takes aspects like transportation, safety, and affordability into account. Making it possible for people to easily compare the livability of different houses. You can read more on the methodology and sources here.

In its beta form, the site features five cities—New York City, Chicago, San Francisco, London and Berlin. When you click on the New York portal, for instance, you can search for the place you want to know more about by borough, zip code, or address. Using New York as an example, it looks like this….(More)

Embracing Crowdsourcing

Paper by Jesse A. Sievers on “A Strategy for State and Local Governments Approaching “Whole Community” Emergency Planning”: “Over the last century, state and local governments have been challenged to keep proactive, emergency planning efforts ahead of the after-the-disaster, response efforts. After moving from decentralized to centralized planning efforts, the most recent policy has returned to the philosophy that a decentralized planning approach is the most effective way to plan for a disaster. In fact, under the Obama administration, a policy of using the “whole community” approach to emergency planning has been adopted. This approach, however, creates an obvious problem for state and local government practitioners already under pressure for funding, time, and the continuous need for higher and broader expertise—the problem of how to actually incorporate the whole community into emergency planning efforts. This article suggests one such approach, crowdsourcing, as an option for local governments. The crowdsourcer-problem-crowd-platform-solution (CPCPS) model is suggested as an initial framework for practitioners seeking a practical application and basic comprehension. The model, discussion, and additional examples in this essay provide a skeletal framework for state and local governments wishing to reach the whole community while under the constraints of time, budget, and technical expertise….(More).

Why Google’s Waze Is Trading User Data With Local Governments

Parmy Olson at Forbes: “In Rio de Janeiro most eyes are on the final, nail-biting matches of the World Cup. Over in the command center of the city’s department of transport though, they’re on a different set of screens altogether.

Planners there are watching the aggregated data feeds of thousands of smartphones being walked or driven around a city, thanks to two popular travel apps, Waze and Moovit.

The goal is traffic management, and it involves swapping data for data. More cities are lining up to get access, and while the data the apps are sharing is all anonymous for now, identifying details could get more specific if cities like what they see, and people become more comfortable with being monitored through their smartphones in return for incentives.

Rio is the first city in the world to collect real-time data both from drivers who use the Waze navigation app and pedestrians who use the public-transportation app Moovit, giving it an unprecedented view on thousands of moving points across the sprawling city. Rio is also talking to the popular cycling app Strava to start monitoring how cyclists are moving around the city too.

All three apps are popular, consumer services which, in the last few months, have found a new way to make their crowdsourced data useful to someone other than advertisers. While consumers use Waze and Moovit to get around, both companies are flipping the use case and turning those millions of users into a network of sensors that municipalities can tap into for a better view on traffic and hazards. Local governments can also use these apps as a channel to send alerts.

On an average day in June, Rio’s transport planners could get an aggregated view of 110,000 drivers (half a million over the course of the month), and see nearly 60,000 incidents being reported each day – everything from built-up traffic, to hazards on the road, Waze says. Till now they’ve been relying on road cameras and other basic transport-department information.

What may be especially tantalizing for planners is the super-accurate read Waze gets on exactly where drivers are going, by pinging their phones’ GPS once every second. The app can tell how fast a driver is moving and even get a complete record of their driving history, according to Waze spokesperson Julie Mossler. (UPDATE: Since this story was first published Waze has asked to clarify that it separates users’ names and their 30-day driving info. The driving history is categorized under an alias.)

This passively-tracked GPS data “is not something we share,” she adds. Waze, which Google bought last year for $1.3 billion, can turn the data spigots on and off through its application programing interface (API).

Waze has been sharing user data with Rio since summer 2013 and it just signed up the State of Florida. It says more departments of transport are in the pipeline.

But none of these partnerships are making Waze any money. The app’s currency of choice is data. “It’s a two-way street,” says Mossler. “Literally.”

In return for its user updates, Waze gets real-time information from Rio on highways, from road sensors and even from cameras, while Florida will give the app data on construction projects or city events.

Florida’s department of transport could not be reached for comment, but one of its spokesmen recently told a local news station: “We’re going to share our information, our camera images, all of our information that comes from the sensors on the roadway, and Waze is going to share its data with us.”…

To get Moovit’s data, municipalities download a web interface that gives them an aggregated view of where pedestrians using Moovit are going. In return, the city feeds Moovit’s database with a stream of real-time GPS data for buses and trains, and can issue transport alerts to Moovit’s users. Erez notes the cities aren’t allowed to make “any sort of commercial approach to the users.”

Erez may be saving that for advertisers, an avenue he says he’s still exploring. For now getting data from cities is the bigger priority. It gives Moovit “a competitive advantage,” he says.

Cycling app Strava also recently started sharing its real-time user data as part of a paid-for service called Strava Metro.

Municipalities pay 80 cents a year for every Strava member being tracked. Metro only launched in May, but it already counts the state of Oregon; London, UK; Glasgow, Scotland; Queensland, Austalia and Evanston, Illinois as customers.

….

Privacy advocates will naturally want to keep a wary eye on what data is being fed to cities, and that it doesn’t leak or get somehow misused by City Hall. The data-sharing might not be ubiquitous enough for that to be a problem yet, and it should be noted that any kind of deal making with the public sector can get wrapped up in bureaucracy and take years to get off the ground.

For now Waze says it’s acting for the public good….(More)