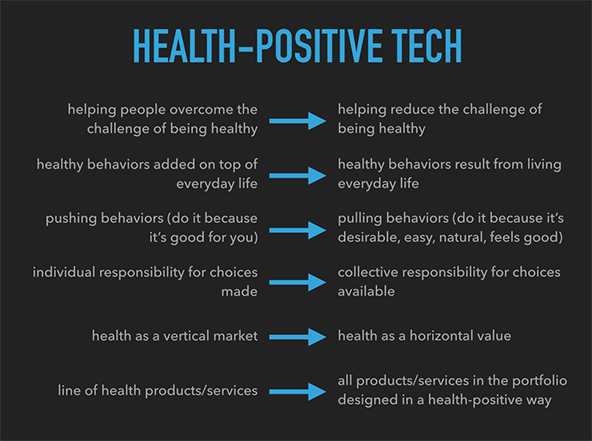

Article by By Sara J. Singer, Stephen Downs, Grace Ann Joseph, Neha Chaudhary, Christopher Gardner, Nina Hersher, Kelsey P. Mellard, Norma Padrón & Yennie Solheim: “….Aligning the technology sector with a societal goal of greater health and well-being entails a number of shifts in thinking. The most fundamental is understanding health not as a vertical market segment, but as a horizontal value: In addition to developing a line of health products or services, health should be expressed across a company’s full portfolio of products and services. Rather than pushing behaviors on people through information and feedback, technology companies should also pull behaviors from people by changing the environment and products they are offered; in addition to developing technology to help people overcome the challenge of being healthy, we need to envision technology that helps to reduce the challenges to being healthy. And in addition to holding individuals responsible for choices that they make, we also need to recognize the collective responsibility that society bears for the choices it makes available.

How to catalyze these shifts?

To find out, we convened a “tech-enabled health,” in which 50 entrepreneurs, leaders from large technology companies, investors, policymakers, clinicians, and public health experts designed a hands-on, interactive, and substantively focused agenda. Participants brainstormed ways that consumer-facing technologies could help people move more, eat better, sleep well, stay socially connected, and reduce stress. In groups and collectively, participants also considered ways in which ideas related and might be synergistic, potential barriers and contextual conditions that might impede or support transformation, and strategies for catalyzing the desired shift. Participants were mixed in terms of sector, discipline, and gender (though the attendees were not as diverse in terms of race/ethnicity or economic strata as the users we potentially wanted to impact—a limitation noted by participants). We intentionally maintained a positive tone, emphasizing potential benefits of shifting toward a health-positive approach, rather than bemoaning the negative role that technology can play….(More)”.