Jim Yong Kim at World Economic Forum: “Good governance is critical for all countries around the world today. When it doesn’t exist, many governments fail to deliver public services effectively, health and education services are often substandard and corruption persists in rich and poor countries alike, choking opportunity and growth. It will be difficult to reduce extreme poverty — let alone end it — without addressing the importance of good governance.

But this is not a hopeless situation. In fact, a new wave of progress on governance suggests we may be on the threshold of a transformational era. Countries are tapping into some of the most powerful forces in the world today to improve services and transparency. These forces include the spread of information technology and its convergence with grassroots movements for transparency, accountability and citizen empowerment. In some places, this convergence is easing the path to better-performing and more accountable governments.

The Philippines is a good example of a country embracing good governance. During a recent visit, I spoke with President Benigno Aquino about his plans to reduce poverty, create jobs, and ensure that economic growth is inclusive. He talked in great detail about how improving governance is a fundamentally important part of their strategy. The government has opened government data and contract information so citizens can see how their tax money is spent. The Foreign Aid Transparency Hub, launched after Typhoon Yolanda, offers a real-time look at pledges made and money delivered for typhoon recovery. Geo-tagging tools monitor assistance for people affected by the typhoon.

Opening budgets to scrutiny

This type of openness is spreading. Now many countries that once withheld information are opening their data and budgets to public scrutiny.

Late last year, my organization, the World Bank Group, established the Open Budgets Portal, a repository for budget data worldwide. So far, 13 countries have posted their entire public spending datasets online — including Togo, the first fragile state to do so.

In 2011, we helped Moldova become the first country in central Europe to launch an open data portal and put its expenditures online. Now the public and media can access more than 700 datasets, and are asking for more.

The original epicenter of the Arab Spring, Tunisia, recently passed a new constitution and is developing the first open budget data portal in the Middle East and North Africa. Tunisia has taken steps towards citizen engagement by developing a citizens’ budget and civil society-led platforms such as Marsoum41, to support freedom of information requests, including via mobile.

Using technology to improve services

Countries also are tapping into technology to improve public and private services. Estonia is famous for building an information technology infrastructure that has permitted widespread use of electronic services — everything from filing taxes online to filling doctors’ drug prescriptions.

In La Paz, Bolivia, a citizen feedback system known as OnTrack allows residents of one of the city’s marginalized neighbourhoods to send a text message on their mobile phones to provide feedback, make suggestions or report a problem related to public services.

In Pakistan, government departments in Punjab are using smart phones to collect real-time data on the activities of government field staff — including photos and geo-tags — to help reduce absenteeism and lax performance….”

Technology’s Crucial Role in the Fight Against Hunger

Crowdsourcing, predictive analytics and other new tools could go far toward finding innovative solutions for America’s food insecurity.

National Geographic recently sent three photographers to explore hunger in the United States. It was an effort to give a face to a very troubling statistic: Even today, one-sixth of Americans do not have enough food to eat. Fifty million people in this country are “food insecure” — having to make daily trade-offs among paying for food, housing or medical care — and 17 million of them skip at least one meal a day to get by. When choosing what to eat, many of these individuals must make choices between lesser quantities of higher-quality food and larger quantities of less-nutritious processed foods, the consumption of which often leads to expensive health problems down the road.

This is an extremely serious, but not easily visible, social problem. Nor does the challenge it poses become any easier when poorly designed public-assistance programs continue to count the sauce on a pizza as a vegetable. The deficiencies caused by hunger increase the likelihood that a child will drop out of school, lowering her lifetime earning potential. In 2010 alone, food insecurity cost America $167.5 billion, a figure that includes lost economic productivity, avoidable health-care expenses and social-services programs.

As much as we need specific policy innovations, if we are to eliminate hunger in America food insecurity is just one of many extraordinarily complex and interdependent “systemic” problems facing us that would benefit from the application of technology, not just to identify innovative solutions but to implement them as well. In addition to laudable policy initiatives by such states as Illinois and Nevada, which have made hunger a priority, or Arkansas, which suffers the greatest level of food insecurity but which is making great strides at providing breakfast to schoolchildren, we can — we must — bring technology to bear to create a sustained conversation between government and citizens to engage more Americans in the fight against hunger.

Identifying who is genuinely in need cannot be done as well by a centralized government bureaucracy — even one with regional offices — as it can through a distributed network of individuals and organizations able to pinpoint with on-the-ground accuracy where the demand is greatest. Just as Ushahidi uses crowdsourcing to help locate and identify disaster victims, it should be possible to leverage the crowd to spot victims of hunger. As it stands, attempts to eradicate so-called food deserts are often built around developing solutions for residents rather than with residents. Strategies to date tend to focus on the introduction of new grocery stores or farmers’ markets but with little input from or involvement of the citizens actually affected.

Applying predictive analytics to newly available sources of public as well as private data, such as that regularly gathered by supermarkets and other vendors, could also make it easier to offer coupons and discounts to those most in need. In addition, analyzing nonprofits’ tax returns, which are legally open and available to all, could help map where the organizations serving those in need leave gaps that need to be closed by other efforts. The Governance Lab recently brought together U.S. Department of Agriculture officials with companies that use USDA data in an effort to focus on strategies supporting a White House initiative to use climate-change and other open data to improve food production.

Such innovative uses of technology, which put citizens at the center of the service-delivery process and streamline the delivery of government support, could also speed the delivery of benefits, thus reducing both costs and, every bit as important, the indignity of applying for assistance.

Being open to new and creative ideas from outside government through brainstorming and crowdsourcing exercises using social media can go beyond simply improving the quality of the services delivered. Some of these ideas, such as those arising from exciting new social-science experiments involving the use of incentives for “nudging” people to change their behaviors, might even lead them to purchase more healthful food.

Further, new kinds of public-private collaborative partnerships could create the means for people to produce their own food. Both new kinds of financing arrangements and new apps for managing the shared use of common real estate could make more community gardens possible. Similarly, with the kind of attention, convening and funding that government can bring to an issue, new neighbor-helping-neighbor programs — where, for example, people take turns shopping and cooking for one another to alleviate time away from work — could be scaled up.

Then, too, advances in citizen engagement and oversight could make it more difficult for lawmakers to cave to the pressures of lobbying groups that push for subsidies for those crops, such as white potatoes and corn, that result in our current large-scale reliance on less-nutritious foods. At the same time, citizen scientists reporting data through an app would be able do a much better job than government inspectors in reporting what is and is not working in local communities.

As a society, we may not yet be able to banish hunger entirely. But if we commit to using new technologies and mechanisms of citizen engagement widely and wisely, we could vastly reduce its power to do harm.

Better Governing Through Data

Editorial Board of the New York Times: “Government bureaucracies, as opposed to casual friendships, are seldom in danger from too much information. That is why a new initiative by the New York City comptroller, Scott Stringer, to use copious amounts of data to save money and solve problems, makes such intuitive sense.

Called ClaimStat, it seeks to collect and analyze information on the thousands of lawsuits and claims filed each year against the city. By identifying patterns in payouts and trouble-prone agencies and neighborhoods, the program is supposed to reduce the cost of claims the way CompStat, the fabled data-tracking program pioneered by the New York Police Department, reduces crime.

There is a great deal of money to be saved: In its 2015 budget, the city has set aside $674 million to cover settlements and judgments from lawsuits brought against it. That amount is projected to grow by the 2018 fiscal year to $782 million, which Mr. Stringer notes is more than the combined budgets of the Departments of Aging and Parks and Recreation and the Public Library.

The comptroller’s office issued a report last month that applied the ClaimStat approach to a handful of city agencies: the Police Department, Parks and Recreation, Health and Hospitals Corporation, Environmental Protection and Sanitation. It notes that the Police Department generates the most litigation of any city agency: 9,500 claims were filed against it in 2013, leading to settlements and judgments of $137.2 million.

After adjusting for the crime rate, the report found that several precincts in the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn had far more claims filed against their officers than other precincts in the city. What does that mean? It’s hard to know, but the implications for policy and police discipline would seem to be a challenge that the mayor, police commissioner and precinct commanders need to figure out. The data clearly point to a problem.

Far more obvious conclusions may be reached from ClaimStat data covering issues like park maintenance and sewer overflows. The city’s tree-pruning budget was cut sharply in 2010, and injury claims from fallen tree branches soared. Multimillion-dollar settlements ensued.

The great promise of ClaimStat is making such shortsightedness blindingly obvious. And in exposing problems like persistent flooding from sewer overflows, ClaimStat can pinpoint troubled areas down to the level of city blocks. (We’re looking at you, Canarsie, and Community District 2 on Staten Island.)

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration has offered only mild praise for the comptroller’s excellent idea (“the mayor welcomes all ideas to make the city more effective and better able to serve its citizens”) while noting, perhaps a little defensively, that it is already on top of this, at least where the police are concerned. It has created a “Risk Assessment and Compliance Unit” within the Police Department to examine claims and make recommendations. The mayor’s aides also point out that the city’s payouts have remained flat over the last 12 years, for which they credit a smart risk-assessment strategy that knows when to settle claims and when to fight back aggressively in court.

But the aspiration of a well-run city should not be to hold claims even but to shrink them. And, at a time when anecdotes and rampant theorizing are fueling furious debates over police crime-fighting strategies, it seems beyond arguing that the more actual information, independently examined and publicly available, the better.”

An Air-Quality Monitor You Take with You

MIT Technology Review: “A startup is building a wearable air-quality monitor using a sensing technology that can cheaply detect the presence of chemicals around you in real time. By reporting the information its sensors gather to an app on your smartphone, the technology could help people with respiratory conditions and those who live in highly polluted areas keep tabs on exposure.

Berkeley, California-based Chemisense also plans to crowdsource data from users to show places around town where certain compounds are identified.

Initially, the company plans to sell a $150 wristband geared toward kids with asthma—of which there are nearly 7 million in the U.S., according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention— to help them identify places and pollutants that tend to provoke attacks, and track their exposure to air pollution over time. The company hopes people with other respiratory conditions, and those who are just concerned about air pollution, will be interested, too.

In the U.S., air quality is monitored at thousands of stations across the country; maps and forecasts can be viewed online. But these monitors offer accurate readings only in their location.

Chemisense has not yet made its initial product, but it expects it will be a wristband using polymers treated with charged nanoparticles of carbon such that the polymers swell in the presence of certain chemical vapors, changing the resistance of a circuit.”

Government opens up: 10k active government users on GitHub

GitHub: “In the summer of 2009, The New York Senate was the first government organization to post code to GitHub, and that fall, Washington DC quickly followed suit. By 2011, cities like Miami, Chicago, and New York; Australian, Canadian, and British government initiatives like Gov.uk; and US Federal agencies like the Federal Communications Commission, General Services Administration, NASA, and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau were all coding in the open as they began to reimagine government for the 21st century.

Fast forward to just last year: The White House Open Data Policy is published as a collaborative, living document, San Francisco laws are now forkable, and government agencies are accepting pull requests from every day developers.

This is all part of a larger trend towards government adopting open source practices and workflows — a trend that spans not only software, but data, and policy as well — and the movement shows no signs of slowing, with government usage on GitHub nearly tripling in the past year, to exceed 10,000 active government users today.

How government uses GitHub

When government works in the open, it acknowledges the idea that government is the world’s largest and longest-running open source project. Open data efforts, efforts like the City of Philadelphia’s open flu shot spec, release machine-readable data in open, immediately consumable formats, inviting feedback (and corrections) from the general public, and fundamentally exposing who made what change when, a necessary check on democracy.

Unlike the private sector, however, where open sourcing the “secret sauce” may hurt the bottom line, with government, we’re all on the same team. With the exception of say, football, Illinois and Wisconsin don’t compete with one another, nor are the types of challenges they face unique. Shared code prevents reinventing the wheel and helps taxpayer dollars go further, with efforts like the White House’s recently released Digital Services Playbook, an effort which invites every day citizens to play a role in making government better, one commit at a time.

However, not all government code is open source. We see that adopting these open source workflows for open collaboration within an agency (or with outside contractors) similarly breaks down bureaucratic walls, and gives like-minded teams the opportunity to work together on common challenges.

Government Today

It’s hard to believe that what started with a single repository just five years ago, has blossomed into a movement where today, more than 10,000 government employees use GitHub to collaborate on code, data, and policy each day….

You can learn more about GitHub in government at government.github.com, and if you’re a government employee, be sure to join our semi-private peer group to learn best practices for collaborating on software, data, and policy in the open.”

Public Innovation through Collaboration and Design

New book edited by Christopher Ansell, and Jacob Torfing: “While innovation has long been a major topic of research and scholarly interest for the private sector, it is still an emerging theme in the field of public management. While ‘results-oriented’ public management may be here to stay, scholars and practitioners are now shifting their attention to the process of management and to how the public sector can create ‘value’.

This volume provides insights for practitioners who are interested in developing an innovation strategy for their city, agency, or administration and will be essential reading for scholars, practitioners and students in the field of public policy and public administration.

Contents:

What Cars Did for Today’s World, Data May Do for Tomorrow’s

Quentin Hardy in the New York Times: “New technology products head at us constantly. There’s the latest smartphone, the shiny new app, the hot social network, even the smarter thermostat.

As great (or not) as all these may be, each thing is a small part of a much bigger process that’s rarely admired. They all belong inside a world-changing ecosystem of digital hardware and software, spreading into every area of our lives.

Thinking about what is going on behind the scenes is easier if we consider the automobile, also known as “the machine that changed the world.” Cars succeeded through the widespread construction of highways and gas stations. Those things created a global supply chain of steel plants and refineries. Seemingly unrelated things, including suburbs, fast food and drive-time talk radio, arose in the success.

Today’s dominant industrial ecosystem is relentlessly acquiring and processing digital information. It demands newer and better ways of collecting, shipping, and processing data, much the way cars needed better road building. And it’s spinning out its own unseen businesses.

A few recent developments illustrate the new ecosystem. General Electric plans to announce Monday that it has created a “data lake” method of analyzing sensor information from industrial machinery in places like railroads, airlines, hospitals and utilities. G.E. has been putting sensors on everything it can for a couple of years, and now it is out to read all that information quickly.

The company, working with an outfit called Pivotal, said that in the last three months it has looked at information from 3.4 million miles of flights by 24 airlines using G.E. jet engines. G.E. said it figured out things like possible defects 2,000 times as fast as it could before.

The company has to, since it’s getting so much more data. “In 10 years, 17 billion pieces of equipment will have sensors,” said William Ruh, vice president of G.E. software. “We’re only one-tenth of the way there.”

It hardly matters if Mr. Ruh is off by five billion or so. Billions of humans are already augmenting that number with their own packages of sensors, called smartphones, fitness bands and wearable computers. Almost all of that will get uploaded someplace too.

Shipping that data creates challenges. In June, researchers at the University of California, San Diego announced a method of engineering fiber optic cable that could make digital networks run 10 times faster. The idea is to get more parts of the system working closer to the speed of light, without involving the “slow” processing of electronic semiconductors.

“We’re going from millions of personal computers and billions of smartphones to tens of billions of devices, with and without people, and that is the early phase of all this,” said Larry Smarr, drector of the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology, located inside U.C.S.D. “A gigabit a second was fast in commercial networks, now we’re at 100 gigabits a second. A terabit a second will come and go. A petabit a second will come and go.”

In other words, Mr. Smarr thinks commercial networks will eventually be 10,000 times as fast as today’s best systems. “It will have to grow, if we’re going to continue what has become our primary basis of wealth creation,” he said.

Add computation to collection and transport. Last month, U.C. Berkeley’s AMP Lab, created two years ago for research into new kinds of large-scale computing, spun out a company called Databricks, that uses new kinds of software for fast data analysis on a rental basis. Databricks plugs into the one million-plus computer servers inside the global system of Amazon Web Services, and will soon work inside similar-size megacomputing systems from Google and Microsoft.

It was the second company out of the AMP Lab this year. The first, called Mesosphere, enables a kind of pooling of computing services, building the efficiency of even million-computer systems….”

Monitoring Arms Control Compliance With Web Intelligence

Chris Holden and Maynard Holliday at Commons Lab: “Traditional monitoring of arms control treaties, agreements, and commitments has required the use of National Technical Means (NTM)—large satellites, phased array radars, and other technological solutions. NTM was a good solution when the treaties focused on large items for observation, such as missile silos or nuclear test facilities. As the targets of interest have shrunk by orders of magnitude, the need for other, more ubiquitous, sensor capabilities has increased. The rise in web-based, or cloud-based, analytic capabilities will have a significant influence on the future of arms control monitoring and the role of citizen involvement.

Since 1999, the U.S. Department of State has had at its disposal the Key Verification Assets Fund (V Fund), which was established by Congress. The Fund helps preserve critical verification assets and promotes the development of new technologies that support the verification of and compliance with arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament requirements.

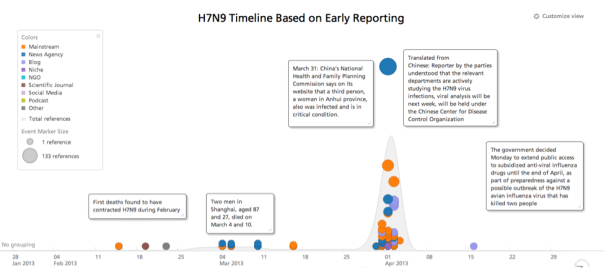

Sponsored by the V Fund to advance web-based analytic capabilities, Sandia National Laboratories, in collaboration with Recorded Future (RF), synthesized open-source data streams from a wide variety of traditional and nontraditional web sources in multiple languages along with topical texts and articles on national security policy to determine the efficacy of monitoring chemical and biological arms control agreements and compliance. The team used novel technology involving linguistic algorithms to extract temporal signals from unstructured text and organize that unstructured text into a multidimensional structure for analysis. In doing so, the algorithm identifies the underlying associations between entities and events across documents and sources over time. Using this capability, the team analyzed several events that could serve as analogs to treaty noncompliance, technical breakout, or an intentional attack. These events included the H7N9 bird flu outbreak in China, the Shanghai pig die-off and the fungal meningitis outbreak in the United States last year.

For H7N9 we found that open source social media were the first to report the outbreak and give ongoing updates. The Sandia RF system was able to roughly estimate lethality based on temporal hospitalization and fatality reporting. For the Shanghai pig die-off the analysis tracked the rapid assessment by Chinese authorities that H7N9 was not the cause of the pig die-off as had been originally speculated. Open source reporting highlighted a reduced market for pork in China due to the very public dead pig display in Shanghai. Possible downstream health effects were predicted (e.g., contaminated water supply and other overall food ecosystem concerns). In addition, legitimate U.S. food security concerns were raised based on the Chinese purchase of the largest U.S. pork producer (Smithfield) because of a fear of potential import of tainted pork into the United States….

To read the full paper, please click here.”

EU-funded tool to help our brain deal with big data

EU Press Release: “Every single minute, the world generates 1.7 million billion bytes of data, equal to 360,000 DVDs. How can our brain deal with increasingly big and complex datasets? EU researchers are developing an interactive system which not only presents data the way you like it, but also changes the presentation constantly in order to prevent brain overload. The project could enable students to study more efficiently or journalists to cross check sources more quickly. Several museums in Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and the United States have already showed interest in the new technology.

Data is everywhere: it can either be created by people or generated by machines, such as sensors gathering climate information, satellite imagery, digital pictures and videos, purchase transaction records, GPS signals, etc. This information is a real gold mine. But it is also challenging: today’s datasets are so huge and complex to process that they require new ideas, tools and infrastructures.

Researchers within CEEDs (@ceedsproject) are transposing big data into an interactive environment to allow the human mind to generate new ideas more efficiently. They have built what they are calling an eXperience Induction Machine (XIM) that uses virtual reality to enable a user to ‘step inside’ large datasets. This immersive multi-modal environment – located at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona – also contains a panoply of sensors which allows the system to present the information in the right way to the user, constantly tailored according to their reactions as they examine the data. These reactions – such as gestures, eye movements or heart rate – are monitored by the system and used to adapt the way in which the data is presented.

Jonathan Freeman,Professor of Psychology at Goldsmiths, University of London and coordinator of CEEDs, explains: “The system acknowledges when participants are getting fatigued or overloaded with information. And it adapts accordingly. It either simplifies the visualisations so as to reduce the cognitive load, thus keeping the user less stressed and more able to focus. Or it will guide the person to areas of the data representation that are not as heavy in information.”

Neuroscientists were the first group the CEEDs researchers tried their machine on (BrainX3). It took the typically huge datasets generated in this scientific discipline and animated them with visual and sound displays. By providing subliminal clues, such as flashing arrows, the machine guided the neuroscientists to areas of the data that were potentially more interesting to each person. First pilots have already demonstrated the power of this approach in gaining new insights into the organisation of the brain….”

The infrastructure Africa really needs is better data reporting

at Quartz: “This week African leaders met with officials in Washington and agreed to billions of dollars of US investments and infrastructure deals. But the terrible state of statistical reporting in most of Africa means that it will be nearly impossible to gauge how effective these deals are at making Africans, or the American investors, better off.

Data reporting on the continent is sketchy. Just look at the recent GDP revisions of large countries. How is it that Nigeria’s April GDP recalculation catapulted it ahead of South Africa, making it the largest economy in Africa overnight? Or that Kenya’s economy is actually 20% larger (paywall) than previously thought?

Indeed, countries in Africa get noticeably bad scores on the World Bank’s Bulletin Board on Statistical Capacity, an index of data reporting integrity.

A recent working paper from the Center for Global Development (CGD) shows how politics influence the statistics released by many African countries…

But in the long run, dodgy statistics aren’t good for anyone. They “distort the way we understand the opportunities that are available,” says Amanda Glassman, one of the CGD report’s authors. US firms have pledged $14 billion in trade deals at the summit in Washington. No doubt they would like to know whether high school enrollment promises to create a more educated workforce in a given country, or whether its people have been immunized for viruses.

Overly optimistic indicators also distort how a government decides where to focus its efforts. If school enrollment appears to be high, why implement programs intended to increase it?

The CGD report suggests increased funding to national statistical agencies, and making sure that they are wholly independent from their governments. President Obama is talking up $7 billion into African agriculture. But unless cash and attention are given to improving statistical integrity, he may never know whether that investment has borne fruit”