Roberto Saba in The Conversation Global: What do Colombia’s recent plebiscite and Brexit have in common? The surface similarities are clear: both referendums produced outcomes that few experts or citizens expected.

And many considered them a blow to core the social values of peace, integration, development and prosperity.

The unanticipated and widely debated results in Colombia and Great Britain – indeed, the very decision to use the mechanism of popular consultation to identify the citizenry’s will – obliges us to reflect on the future of democratic systems.

Both the British and Colombian plebiscites can be understood as the consequence, not the cause, of a crisis in representative democracy that affects not just these two countries but many others around the world.

The nature of democracy

Democracies recognise that only the people have the legitimacy to decide their destiny. But they also acknowledge that identifying the will of a collective isn’t simple: modern democracies are constitutional, which means that decisions made by the people – usually through their representatives – are limited by the content of the national constitution.

Decisions occasionally made by a constitutional assembly or by a supermajority in congress – say, to ban torture – prevent the government from authorising such action, no matter how dramatic the current social circumstance (a terrorist attack, for instance, or war), or how much a national majority favours the measure.

Constitutional rights and the rules of the democratic game cannot be modified by governments or even by a majority of the people. Democratic communities are bound by the deep constitutional commitments they’ve made to respect human rights and the rule of law.

These beliefs may, of course, be threatened by an occasional challenge. A terrorist attack that fills people with fear and resentment may make them forget, momentarily, that yesterday or two centuries ago – when they were mentally and emotionally far from this blinding, overwhelming event – they made the choice never to torture, anticipating that their desire to do so would be motivated by basic human instinct such as survival or vengeance.

That’s what a constitution is for: defining our shared basic values and goals as a nation, external factors be damned.

Decisions like the ones the Colombian and British people were asked to vote on do not represent mere political choices, such as whether to raise the sales tax or expand free trade.

They were much more akin to constitutional decisions that, depending on their outcomes, would usher in a new era in the lives of those nations. Community identity, rights, the rule of law and peace itself were some of the basic and fundamental values at stake.

The problem with plebiscites

There are many ways to make, validate, and build consensus around fundamental constitutional decisions: parliamentary super-majorities in Chile, constitutional assemblies in Argentina, or state legislature approvalin Mexico and the United States.

In some, such as the current Chilean process designed by Michelle Bachelet’s administration, the people themselves are called to deliberate constitutional choices in public forums.

And yet in the Colombian and the British cases, the government chose the riskiest of all known methods for identifying popular constitutional will. In this kind of process, complex questions are put forth in a way that makes it seem quite simple, because they must be answered in a single word: yes or no….

these difficult and deep concerns cannot be decided via a confusing question and a binary response.

Plebiscites are not necessarily democratic for those of us who believe that the justification of democracy as a superior political system superior is not because it counts heads, but because of the deliberative process that precedes decisions.

Thus, Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s famous plebscita were not democratic exercises. A democratic exercise only exists when a diverse exchange of perspectives, opinions, and information can take place. The more diverse those inputs, the more legitimate the outcome of the vote.

The plebiscite constitutes the opposite of everything that we hope will happen in constitutional decision-making: the question is designed and imposed by those in power and the probability or suspicion that their formulation is biased is very high.

What’s more, public deliberation about the question may happen, but it’s not a certainty. Are people talking to their neighbours? Are they developing their position and hearing alternative approaches, which is the best way to make an educated decision?…

Constitutional decisions, which is to say the decisions political communities make rarely but carefully over the course of their history – what Bruce Ackerman calls “constitutional moments” – cannot be decided by plebiscite.

The popular will is too elusive for us to fool ourselves into thinking we can capture it with a single question….(More)”

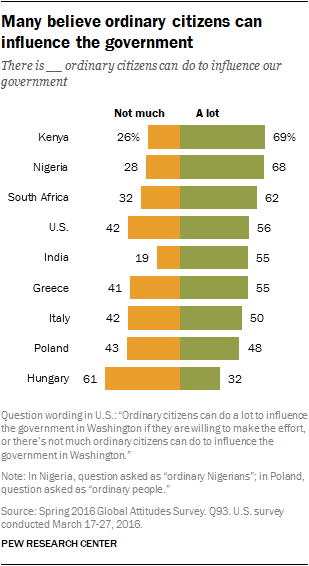

As a new nine-country Pew Research Center survey on the strengths and limitations of civic engagement illustrates, there is a common perception that government is run for the benefit of the few, rather than the many in both emerging democracies and more mature democracies that have faced economic challenges in recent years. In eight of nine nations surveyed, more than half say government is run for the benefit of only a few groups in society, not for all people.1

As a new nine-country Pew Research Center survey on the strengths and limitations of civic engagement illustrates, there is a common perception that government is run for the benefit of the few, rather than the many in both emerging democracies and more mature democracies that have faced economic challenges in recent years. In eight of nine nations surveyed, more than half say government is run for the benefit of only a few groups in society, not for all people.1