Paper by Ayan Mukhopadhyay: “Emergency response management (ERM) is a challenge faced by communities across the globe. First responders must respond to various incidents, such as fires, traffic accidents, and medical emergencies. They must respond quickly to incidents to minimize the risk to human life. Consequently, considerable attention has been devoted to studying emergency incidents and response in the last several decades. In particular, data-driven models help reduce human and financial loss and improve design codes, traffic regulations, and safety measures. This tutorial paper explores four sub-problems within emergency response: incident prediction, incident detection, resource allocation, and resource dispatch. We aim to present mathematical formulations for these problems and broad frameworks for each problem. We also share open-source (synthetic) data from a large metropolitan area in the USA for future work on data-driven emergency response…(More)”.

Open Data on GitHub: Unlocking the Potential of AI

Paper by Anthony Cintron Roman, Kevin Xu, Arfon Smith, Jehu Torres Vega, Caleb Robinson, Juan M Lavista Ferres: “GitHub is the world’s largest platform for collaborative software development, with over 100 million users. GitHub is also used extensively for open data collaboration, hosting more than 800 million open data files, totaling 142 terabytes of data. This study highlights the potential of open data on GitHub and demonstrates how it can accelerate AI research. We analyze the existing landscape of open data on GitHub and the patterns of how users share datasets. Our findings show that GitHub is one of the largest hosts of open data in the world and has experienced an accelerated growth of open data assets over the past four years. By examining the open data landscape on GitHub, we aim to empower users and organizations to leverage existing open datasets and improve their discoverability — ultimately contributing to the ongoing AI revolution to help address complex societal issues. We release the three datasets that we have collected to support this analysis as open datasets at this https URL…(More)”

Ethical Considerations Towards Protestware

Paper by Marc Cheong, Raula Gaikovina Kula, and Christoph Treude: “A key drawback to using a Open Source third-party library is the risk of introducing malicious attacks. In recently times, these threats have taken a new form, when maintainers turn their Open Source libraries into protestware. This is defined as software containing political messages delivered through these libraries, which can either be malicious or benign. Since developers are willing to freely open-up their software to these libraries, much trust and responsibility are placed on the maintainers to ensure that the library does what it promises to do. This paper takes a look into the possible scenarios where developers might consider turning their Open Source Software into protestware, using an ethico-philosophical lens. Using different frameworks commonly used in AI ethics, we explore the different dilemmas that may result in protestware. Additionally, we illustrate how an open-source maintainer’s decision to protest is influenced by different stakeholders (viz., their membership in the OSS community, their personal views, financial motivations, social status, and moral viewpoints), making protestware a multifaceted and intricate matter…(More)”

Computer: A History of the Information Machine

Updated edition of book by Martin Campbell-Kelly, William Aspray, Nathan Ensmenger, Jeffrey R. Yost; “…traces the history of the computer and shows how business and government were the first to explore its unlimited, information-processing potential. Old-fashioned entrepreneurship combined with scientific know-how inspired now famous computer engineers to create the technology that became IBM. Wartime needs drove the giant ENIAC, the first fully electronic computer. Later, the PC enabled modes of computing that liberated people from room-sized, mainframe computers.

This third edition provides updated analysis on software and computer networking, including new material on the programming profession, social networking, and mobile computing. It expands its focus on the IT industry with fresh discussion on the rise of Google and Facebook as well as how powerful applications are changing the way we work, consume, learn, and socialize. Computer is an insightful look at the pace of technological advancement and the seamless way computers are integrated into the modern world. Through comprehensive history and accessible writing, Computer is perfect for courses on computer history, technology history, and information and society, as well as a range of courses in the fields of computer science, communications, sociology, and management…(More)”.

How existential risk became the biggest meme in AI

Article by Will Douglas Heaven: “Who’s afraid of the big bad bots? A lot of people, it seems. The number of high-profile names that have now made public pronouncements or signed open letters warning of the catastrophic dangers of artificial intelligence is striking.

Hundreds of scientists, business leaders, and policymakers have spoken up, from deep learning pioneers Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio to the CEOs of top AI firms, such as Sam Altman and Demis Hassabis, to the California congressman Ted Lieu and the former president of Estonia Kersti Kaljulaid.

The starkest assertion, signed by all those figures and many more, is a 22-word statement put out two weeks ago by the Center for AI Safety (CAIS), an agenda-pushing research organization based in San Francisco. It proclaims: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

The wording is deliberate. “If we were going for a Rorschach-test type of statement, we would have said ‘existential risk’ because that can mean a lot of things to a lot of different people,” says CAIS director Dan Hendrycks. But they wanted to be clear: this was not about tanking the economy. “That’s why we went with ‘risk of extinction’ even though a lot of us are concerned with various other risks as well,” says Hendrycks.

We’ve been here before: AI doom follows AI hype. But this time feels different. The Overton window has shifted. What were once extreme views are now mainstream talking points, grabbing not only headlines but the attention of world leaders. “The chorus of voices raising concerns about AI has simply gotten too loud to be ignored,” says Jenna Burrell, director of research at Data and Society, an organization that studies the social implications of technology.

What’s going on? Has AI really become (more) dangerous? And why are the people who ushered in this tech now the ones raising the alarm?

It’s true that these views split the field. Last week, Yann LeCun, chief scientist at Meta and joint recipient with Hinton and Bengio of the 2018 Turing Award, called the doomerism “preposterously ridiculous.” Aidan Gomez, CEO of the AI firm Cohere, said it was “an absurd use of our time.”

Others scoff too. “There’s no more evidence now than there was in 1950 that AI is going to pose these existential risks,” says Signal president Meredith Whittaker, who is cofounder and former director of the AI Now Institute, a research lab that studies the social and policy implications of artificial intelligence. “Ghost stories are contagious—it’s really exciting and stimulating to be afraid.”

“It is also a way to skim over everything that’s happening in the present day,” says Burrell. “It suggests that we haven’t seen real or serious harm yet.”…(More)”.

Collective Intelligence to Co-Create the Cities of the Future: Proposal of an Evaluation Tool for Citizen Initiatives

Paper by Fanny E. Berigüete, Inma Rodriguez Cantalapiedra, Mariana Palumbo and Torsten Masseck: “Citizen initiatives (CIs), through their activities, have become a mechanism to promote empowerment, social inclusion, change of habits, and the transformation of neighbourhoods, influencing their sustainability, but how can this impact be measured? Currently, there are no tools that directly assess this impact, so our research seeks to describe and evaluate the contributions of CIs in a holistic and comprehensive way, respecting the versatility of their activities. This research proposes an evaluation system of 33 indicators distributed in 3 blocks: social cohesion, urban metabolism, and transformation potential, which can be applied through a questionnaire. This research applied different methods such as desk study, literature review, and case study analysis. The evaluation of case studies showed that the developed evaluation system well reflects the individual contribution of CIs to sensitive and important aspects of neighbourhoods, with a lesser or greater impact according to the activities they carry out and the holistic conception they have of sustainability. Further implementation and validation of the system in different contexts is needed, but it is a novel and interesting proposal that will favour decision making for the promotion of one or another type of initiative according to its benefits and the reality and needs of the neighbourhood…(More)”.

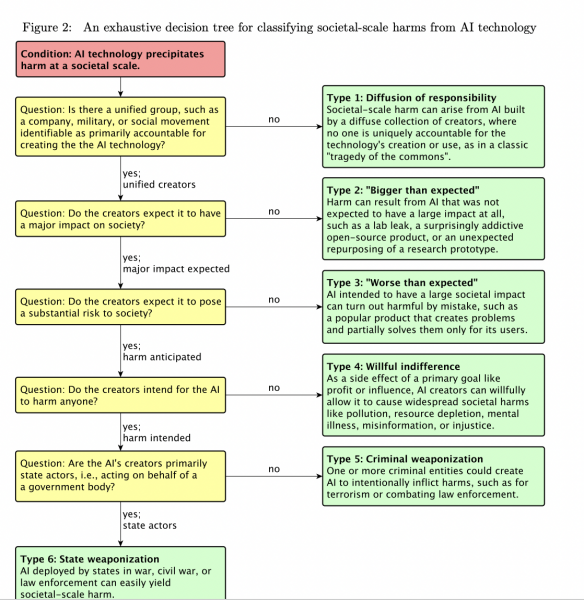

TASRA: a Taxonomy and Analysis of Societal-Scale Risks from AI

Paper by Andrew Critch and Stuart Russell: “While several recent works have identified societal-scale and extinction-level risks to humanity arising from artificial intelligence, few have attempted an {\em exhaustive taxonomy} of such risks. Many exhaustive taxonomies are possible, and some are useful — particularly if they reveal new risks or practical approaches to safety. This paper explores a taxonomy based on accountability: whose actions lead to the risk, are the actors unified, and are they deliberate? We also provide stories to illustrate how the various risk types could each play out, including risks arising from unanticipated interactions of many AI systems, as well as risks from deliberate misuse, for which combined technical and policy solutions are indicated…(More)”.

The A.I. Revolution Will Change Work. Nobody Agrees How.

Sarah Kessler in The New York Times: “In 2013, researchers at Oxford University published a startling number about the future of work: 47 percent of all United States jobs, they estimated, were “at risk” of automation “over some unspecified number of years, perhaps a decade or two.”

But a decade later, unemployment in the country is at record low levels. The tsunami of grim headlines back then — like “The Rich and Their Robots Are About to Make Half the World’s Jobs Disappear” — look wildly off the mark.

But the study’s authors say they didn’t actually mean to suggest doomsday was near. Instead, they were trying to describe what technology was capable of.

It was the first stab at what has become a long-running thought experiment, with think tanks, corporate research groups and economists publishing paper after paper to pinpoint how much work is “affected by” or “exposed to” technology.

In other words: If cost of the tools weren’t a factor, and the only goal was to automate as much human labor as possible, how much work could technology take over?

When the Oxford researchers, Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael A. Osborne, were conducting their study, IBM Watson, a question-answering system powered by artificial intelligence, had just shocked the world by winning “Jeopardy!” Test versions of autonomous vehicles were circling roads for the first time. Now, a new wave of studies follows the rise of tools that use generative A.I.

In March, Goldman Sachs estimated that the technology behind popular A.I. tools such as DALL-E and ChatGPT could automate the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs. Researchers at Open AI, the maker of those tools, and the University of Pennsylvania found that 80 percent of the U.S. work force could see an effect on at least 10 percent of their tasks.

“There’s tremendous uncertainty,” said David Autor, a professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who has been studying technological change and the labor market for more than 20 years. “And people want to provide those answers.”

But what exactly does it mean to say that, for instance, the equivalent of 300 million full-time jobs could be affected by A. I.?

It depends, Mr. Autor said. “Affected could mean made better, made worse, disappeared, doubled.”…(More)”.

Politicians love to appeal to common sense – but does it trump expertise?

Essay by Magda Osman: “Politicians love to talk about the benefits of “common sense” – often by pitting it against the words of “experts and elites”. But what is common sense? Why do politicians love it so much? And is there any evidence that it ever trumps expertise? Psychology provides a clue.

We often view common sense as an authority of collective knowledge that is universal and constant, unlike expertise. By appealing to the common sense of your listeners, you therefore end up on their side, and squarely against the side of the “experts”. But this argument, like an old sock, is full of holes.

Experts have gained knowledge and experience in a given speciality. In which case politicians are experts as well. This means a false dichotomy is created between the “them” (let’s say scientific experts) and “us” (non-expert mouthpieces of the people).

Common sense is broadly defined in research as a shared set of beliefs and approaches to thinking about the world. For example, common sense is often used to justify that what we believe is right or wrong, without coming up with evidence.

But common sense isn’t independent of scientific and technological discoveries. Common sense versus scientific beliefs is therefore also a false dichotomy. Our “common” beliefs are informed by, and inform, scientific and technology discoveries…

The idea that common sense is universal and self-evident because it reflects the collective wisdom of experience – and so can be contrasted with scientific discoveries that are constantly changing and updated – is also false. And the same goes for the argument that non-experts tend to view the world the same way through shared beliefs, while scientists never seem to agree on anything.

Just as scientific discoveries change, common sense beliefs change over time and across cultures. They can also be contradictory: we are told “quit while you are ahead” but also “winners never quit”, and “better safe than sorry” but “nothing ventured nothing gained”…(More)”

From Ethics to Law: Why, When, and How to Regulate AI

Paper by Simon Chesterman: “The past decade has seen a proliferation of guides, frameworks, and principles put forward by states, industry, inter- and non-governmental organizations to address matters of AI ethics. These diverse efforts have led to a broad consensus on what norms might govern AI. Far less energy has gone into determining how these might be implemented — or if they are even necessary. This chapter focuses on the intersection of ethics and law, in particular discussing why regulation is necessary, when regulatory changes should be made, and how it might work in practice. Two specific areas for law reform address the weaponization and victimization of AI. Regulations aimed at general AI are particularly difficult in that they confront many ‘unknown unknowns’, but the threat of uncontrollable or uncontainable AI became more widely discussed with the spread of large language models such as ChatGPT in 2023. Additionally, however, there will be a need to prohibit some conduct in which increasingly lifelike machines are the victims — comparable, perhaps, to animal cruelty laws…(More)”