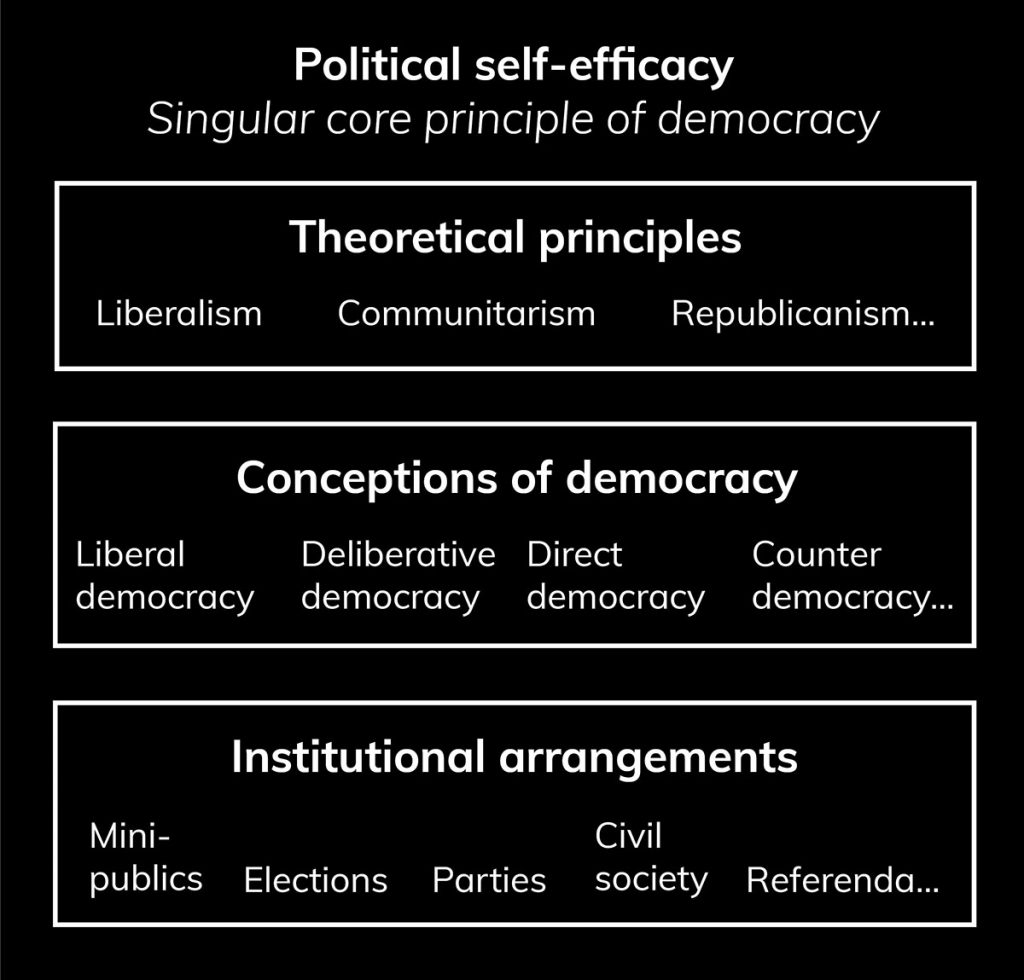

Blog by Toralf Stark, Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann and Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach: “…Many criticisms of conceptions of democracy are directed more at the institutional design than at its normative underpinnings. These include such things as the concept of representativeness. We propose focussing more on the normative foundations assessed by the different institutional frameworks than discussing the institutional frameworks themselves. We develop a new concept, which we call the ‘core principle of democracy’. By doing so, we address the conceptual and methodological puzzles theoretically and empirically. Thus, we embrace a paradigm shift.

Collecting data is ultimately meaningless if we do not find ways to assess, summarise and theorise it. Kei Nishiyama argued we must ‘shift our attention away from the concept of democracy and towards concepts of democracy’. By the term concept we, in line with Nishiyama, are following Rawls. Rawls claimed that ‘the concept of democracy refers to a single, common principle that transcends differences and on which everyone agrees’. In contrast with this, ‘ideas of democracy (…) refer to different, sometimes contested ideas based on a common concept’. This is what Laurence Whitehead calls the ‘timeless essence of democracy’….

Democracy is a latent construct and, by nature, not directly observable. Nevertheless, we are searching for indicators and empirically observable characteristics we can assign to democratic conceptions. However, by focusing only on specific patterns of institutions, only sometimes derived from theoretical considerations, we block our view of its multiple meanings. Thus, we’ve no choice but to search behind the scenes for the underlying ‘core’ principle the institutions serve.

The singular core principle that all concepts of democracy seek to realise is political self-efficacy…(More)”.