OECD Report: “This first edition of the OECD Anti-Corruption and Integrity Outlook analyses Member countries’ efforts to uphold integrity and fight corruption. Based on data from the Public Integrity Indicators, it analyses the performance of countries’ integrity frameworks, and explores how some of the main challenges to governments today (including the green transition, artificial intelligence, and foreign interference) are increasing corruption and integrity risks for countries. It also addresses how the shortcomings in integrity systems can impede countries’ responses to these major challenges. In providing a snapshot of how countries are performing today, the Outlook supports strategic planning and policy work to strengthen public integrity for the future…(More)”.

Big data for everyone

Article by Henrietta Howells: “Raw neuroimaging data require further processing before they can be used for scientific or clinical research. Traditionally, this could be accomplished with a single powerful computer. However, much greater computing power is required to analyze the large open-access cohorts that are increasingly being released to the community. And processing pipelines are inconsistently scripted, which can hinder reproducibility efforts. This creates a barrier for labs lacking access to sufficient resources or technological support, potentially excluding them from neuroimaging research. A paper by Hayashi and colleagues in Nature Methods offers a solution. They present https://brainlife.io, a freely available, web-based platform for secure neuroimaging data access, processing, visualization and analysis. It leverages ‘opportunistic computing’, which pools processing power from commercial and academic clouds, making it accessible to scientists worldwide. This is a step towards lowering the barriers for entry into big data neuroimaging research…(More)”.

We don’t need an AI manifesto — we need a constitution

Article by Vivienne Ming: “Loans drive economic mobility in America, even as they’ve been a historically powerful tool for discrimination. I’ve worked on multiple projects to reduce that bias using AI. What I learnt, however, is that even if an algorithm works exactly as intended, it is still solely designed to optimise the financial returns to the lender who paid for it. The loan application process is already impenetrable to most, and now your hopes for home ownership or small business funding are dying in a 50-millisecond computation…

In law, the right to a lawyer and judicial review are a constitutional guarantee in the US and an established civil right throughout much of the world. These are the foundations of your civil liberties. When algorithms act as an expert witness, testifying against you but immune to cross examination, these rights are not simply eroded — they cease to exist.

People aren’t perfect. Neither ethics training for AI engineers nor legislation by woefully uninformed politicians can change that simple truth. I don’t need to assume that Big Tech chief executives are bad actors or that large companies are malevolent to understand that what is in their self-interest is not always in mine. The framers of the US Constitution recognised this simple truth and sought to leverage human nature for a greater good. The Constitution didn’t simply assume people would always act towards that greater good. Instead it defined a dynamic mechanism — self-interest and the balance of power — that would force compromise and good governance. Its vision of treating people as real actors rather than better angels produced one of the greatest frameworks for governance in history.

Imagine you were offered an AI-powered test for post-partum depression. My company developed that very test and it has the power to change your life, but you may choose not to use it for fear that we might sell the results to data brokers or activist politicians. You have a right to our AI acting solely for your health. It was for this reason I founded an independent non-profit, The Human Trust, that holds all of the data and runs all of the algorithms with sole fiduciary responsibility to you. No mother should have to choose between a life-saving medical test and her civil rights…(More)”.

A Fourth Wave of Open Data? Exploring the Spectrum of Scenarios for Open Data and Generative AI

Report by Hannah Chafetz, Sampriti Saxena, and Stefaan G. Verhulst: “Since late 2022, generative AI services and large language models (LLMs) have transformed how many individuals access, and process information. However, how generative AI and LLMs can be augmented with open data from official sources and how open data can be made more accessible with generative AI – potentially enabling a Fourth Wave of Open Data – remains an under explored area.

For these reasons, The Open Data Policy Lab (a collaboration between The GovLab and Microsoft) decided to explore the possible intersections between open data from official sources and generative AI. Throughout the last year, the team has conducted a range of research initiatives about the potential of open data and generative including a panel discussion, interviews, and Open Data Action Labs – a series of design sprints with a diverse group of industry experts.

These initiatives were used to inform our latest report, “A Fourth Wave of Open Data? Exploring the Spectrum of Scenarios for Open Data and Generative AI,” (May 2024) which provides a new framework and recommendations to support open data providers and other interested parties in making open data “ready” for generative AI…

The report outlines five scenarios in which open data from official sources (e.g. open government and open research data) and generative AI can intersect. Each of these scenarios includes case studies from the field and a specific set of requirements that open data providers can focus on to become ready for a scenario. These include…(More)” (Arxiv).

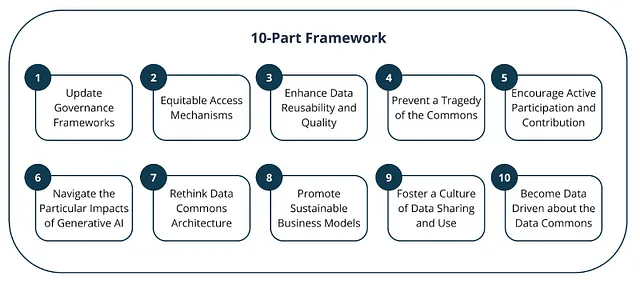

“Data Commons”: Under Threat by or The Solution for a Generative AI Era ? Rethinking Data Access and Re-us

Article by Stefaan G. Verhulst, Hannah Chafetz and Andrew Zahuranec: “One of the great paradoxes of our datafied era is that we live amid both unprecedented abundance and scarcity. Even as data grows more central to our ability to promote the public good, so too does it remain deeply — and perhaps increasingly — inaccessible and privately controlled. In response, there have been growing calls for “data commons” — pools of data that would be (self-)managed by distinctive communities or entities operating in the public’s interest. These pools could then be made accessible and reused for the common good.

Data commons are typically the results of collaborative and participatory approaches to data governance [1]. They offer an alternative to the growing tendency toward privatized data silos or extractive re-use of open data sets, instead emphasizing the communal and shared value of data — for example, by making data resources accessible in an ethical and sustainable way for purposes in alignment with community values or interests such as scientific research, social good initiatives, environmental monitoring, public health, and other domains.

Data commons can today be considered (the missing) critical infrastructure for leveraging data to advance societal wellbeing. When designed responsibly, they offer potential solutions for a variety of wicked problems, from climate change to pandemics and economic and social inequities. However, the rapid ascent of generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies is changing the rules of the game, leading both to new opportunities as well as significant challenges for these communal data repositories.

On the one hand, generative AI has the potential to unlock new insights from data for a broader audience (through conversational interfaces such as chats), fostering innovation, and streamlining decision-making to serve the public interest. Generative AI also stands out in the realm of data governance due to its ability to reuse data at a massive scale, which has been a persistent challenge in many open data initiatives. On the other hand, generative AI raises uncomfortable questions related to equitable access, sustainability, and the ethical re-use of shared data resources. Further, without the right guardrails, funding models and enabling governance frameworks, data commons risk becoming data graveyards — vast repositories of unused, and largely unusable, data.

In what follows, we lay out some of the challenges and opportunities posed by generative AI for data commons. We then turn to a ten-part framework to set the stage for a broader exploration on how to reimagine and reinvigorate data commons for the generative AI era. This framework establishes a landscape for further investigation; our goal is not so much to define what an updated data commons would look like but to lay out pathways that would lead to a more meaningful assessment of the design requirements for resilient data commons in the age of generative AI…(More)”

The Age of AI Nationalism and its Effects

Paper by Susan Ariel Aaronson: “This paper aims to illuminate how AI nationalistic policies may backfire. Over time, such actions and policies could alienate allies and prod other countries to adopt “beggar-thy neighbor” approaches to AI (The Economist: 2023; Kim: 2023 Shivakumar et al. 2024). Moreover, AI nationalism could have additional negative spillovers over time. Many AI experts are optimistic about the benefits of AI, whey they are aware of its many risks to democracy, equity, and society. They understand that AI can be a public good when it is used to mitigate complex problems affecting society (Gopinath: 2023; Okolo: 2023). However, when policymakers take steps to advance AI within their borders, they may — perhaps without intending to do so – make it harder for other countries with less capital, expertise, infrastructure, and data prowess to develop AI systems that could meet the needs of their constituents. In so doing, these officials could undermine the potential of AI to enhance human welfare and impede the development of more trustworthy AI around the world. (Slavkovik: 2024; Aaronson: 2023; Brynjolfsson and Unger: 2023; Agrawal et al. 2017).

Governments have many means of nurturing AI within their borders that do not necessarily discriminate between foreign and domestic producers of AI. Nevertheless, officials may be under pressure from local firms to limit the market power of foreign competitors. Officials may also want to use trade (for example, export controls) as a lever to prod other governments to change their behavior (Buchanan: 2020). Additionally, these officials may be acting in what they believe is the nation’s national security interest, which may necessitate that officials rely solely on local suppliers and local control. (GAO: 2021)

Herein the author attempts to illuminate AI nationalism and its consequences by answering 3 questions:

• What are nations doing to nurture AI capacity within their borders?

• Are some of these actions trade distorting?

• What are the implications of such trade-distorting actions?…(More)”

Learning from Ricardo and Thompson: Machinery and Labor in the Early Industrial Revolution, and in the Age of AI

Paper by Daron Acemoglu & Simon Johnson: “David Ricardo initially believed machinery would help workers but revised his opinion, likely based on the impact of automation in the textile industry. Despite cotton textiles becoming one of the largest sectors in the British economy, real wages for cotton weavers did not rise for decades. As E.P. Thompson emphasized, automation forced workers into unhealthy factories with close surveillance and little autonomy. Automation can increase wages, but only when accompanied by new tasks that raise the marginal productivity of labor and/or when there is sufficient additional hiring in complementary sectors. Wages are unlikely to rise when workers cannot push for their share of productivity growth. Today, artificial intelligence may boost average productivity, but it also may replace many workers while degrading job quality for those who remain employed. As in Ricardo’s time, the impact of automation on workers today is more complex than an automatic linkage from higher productivity to better wages…(More)”.

The Human Rights Data Revolution

Briefing by Domenico Zipoli: “… explores the evolving landscape of digital human rights tracking tools and databases (DHRTTDs). It discusses their growing adoption for monitoring, reporting, and implementing human rights globally, while also pinpointing the challenge of insufficient coordination and knowledge sharing among these tools’ developers and users. Drawing from insights of over 50 experts across multiple sectors gathered during two pivotal roundtables organized by the GHRP in 2022 and 2023, this new publication critically evaluates the impact and future of DHRTTDs. It integrates lessons and challenges from these discussions, along with targeted research and interviews, to guide the human rights community in leveraging digital advancements effectively..(More)”.

Technology and the Transformation of U.S. Foreign Policy

Speech by Antony J. Blinken: “Today’s revolutions in technology are at the heart of our competition with geopolitical rivals. They pose a real test to our security. And they also represent an engine of historic possibility – for our economies, for our democracies, for our people, for our planet.

Put another way: Security, stability, prosperity – they are no longer solely analog matters.

The test before us is whether we can harness the power of this era of disruption and channel it into greater stability, greater prosperity, greater opportunity.

President Biden is determined not just to pass this “tech test,” but to ace it.

Our ability to design, to develop, to deploy technologies will determine our capacity to shape the tech future. And naturally, operating from a position of strength better positions us to set standards and advance norms around the world.

But our advantage comes not just from our domestic strength.

It comes from our solidarity with the majority of the world that shares our vision for a vibrant, open, and secure technological future, and from an unmatched network of allies and partners with whom we can work in common cause to pass the “tech test.”

We’re committed not to “digital sovereignty” but “digital solidarity.”

On May 6, the State Department unveiled the U.S. International Cyberspace and Digital Strategy, which treats digital solidarity as our North Star. Solidarity informs our approach not only to digital technologies, but to all key foundational technologies.

So what I’d like to do now is share with you five ways that we’re putting this into practice.

First, we’re harnessing technology for the betterment not just of our people and our friends, but of all humanity.

The United States believes emerging and foundational technologies can and should be used to drive development and prosperity, to promote respect for human rights, to solve shared global challenges.

Some of our strategic rivals are working toward a very different goal. They’re using digital technologies and genomic data collection to surveil their people, to repress human rights.

Pretty much everywhere I go, I hear from government officials and citizens alike about their concerns about these dystopian uses of technology. And I also hear an abiding commitment to our affirmative vision and to the embrace of technology as a pathway to modernization and opportunity.

Our job is to use diplomacy to try to grow this consensus even further – to internationalize and institutionalize our vision of “tech for good.”..(More)”.

Complexity and the Global Governance of AI

Paper by Gordon LaForge et al: “In the coming years, advanced artificial intelligence (AI) systems are expected to bring significant benefits and risks for humanity. Many governments, companies, researchers, and civil society organizations are proposing, and in some cases, building global governance frameworks and institutions to promote AI safety and beneficial development. Complexity thinking, a way of viewing the world not just as discrete parts at the macro level but also in terms of bottom-up and interactive complex adaptive systems, can be a useful intellectual and scientific lens for shaping these endeavors. This paper details how insights from the science and theory of complexity can aid understanding of the challenges posed by AI and its potential impacts on society. Given the characteristics of complex adaptive systems, the paper recommends that global AI governance be based on providing a fit, adaptive response system that mitigates harmful outcomes of AI and enables positive aspects to flourish. The paper proposes components of such a system in three areas: access and power, international relations and global stability; and accountability and liability…(More)”