Stefaan Verhulst

Tom Fox at the Washington Post: “Given the complexity and difficulty of the challenges that government leaders face, encouraging innovation among their workers can pay dividends. Government-wide employee survey data, however, suggest that much more needs to be done to foster this type of culture at many federal organizations.

According to that data, nearly 90 percent of federal employees are looking for ways to be more innovative and effective, but only 54 percent feel encouraged by their leaders to come up with new ways of doing work. To make matters worse, fewer than a third say they believe creativity and innovation are rewarded in their agencies.

It’s worth pausing to examine what sets apart those agencies that do. They tend to have developed innovative cultures by providing forums for employees to share and test new ideas, by encouraging responsible risk-taking, and by occasionally bringing in outside talent for rotational assignments to infuse new thinking into the workplace.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is one example of an agency working at this. In 2010 it created the Idea Lab, with the goal to “remove barriers HHS employees face and promote better ways of working in government.”

It launched an awards program as part of Idea Lab called HHS Innovates to identify promising, new ideas likely to improve effectiveness. And to directly support implementing these ideas, the lab launched HHS Ignites, which provides teams with seed funding of $5,000 and a three-month timeframe to work on approved action plans. When the agency needs a shot of outside inspiration, it has its Entrepreneurs-in-Residence program, which enlists experts from the private and nonprofit sectors to join HHS for one or two years to develop new approaches and improve practices….

While the HHS Idea Lab program is a good concept, it’s the agency’s implementation that distinguishes it from other government efforts. Federal leaders elsewhere would be wise to borrow a few of their tactics.

As a starting point, federal leaders should issue a clear call for innovation that demands a measurable result. Too often, leaders ask for changes without any specificity as to the result they are looking to achieve. If you want your employees to be more innovative, you need to set a concrete, data-driven goal — whether that’s to reduce process steps or process times, improve customer satisfaction or reduce costs.

Secondly, you should help your employees take their ideas to implementation by playing equal parts cheerleader and drill sergeant. That is, you need to boost their confidence while at the same time pushing them to develop concrete action plans, experiments and measurements to show their ideas deliver results….(More)”

Paper by Stephan G. Grimmelikhuijsen and Albert J. Meijer in Public Administration Review: “Social media use has become increasingly popular among police forces. The literature suggests that social media use can increase perceived police legitimacy by enabling transparency and participation. Employing data from a large and representative survey of Dutch citizens (N = 4,492), this article tests whether and how social media use affects perceived legitimacy for a major social media platform, Twitter. A negligible number of citizens engage online with the police, and thus the findings reveal no positive relationship between participation and perceived legitimacy. The article shows that by enhancing transparency, Twitter does increase perceived police legitimacy, albeit to a limited extent. Subsequent analysis of the mechanism shows both an affective and a cognitive path from social media use to legitimacy. Overall, the findings suggest that establishing a direct channel with citizens and using it to communicate successes does help the police strengthen their legitimacy, but only slightly and for a small group of interested citizens….(More)”

Paper by Mark Fenster in the European Journal of Social Theory: “Transparency’s importance as an administrative norm seems self-evident. Prevailing ideals of political theory stipulate that the more visible government is, the more democratic, accountable, and legitimate it appears. The disclosure of state information consistently disappoints, however: there is never enough of it, while it often seems not to produce a truer democracy, a more accountable state, better policies, and a more contented populace. This gap between theory and practice suggests that the theoretical assumptions that provide the basis for transparency are wrong. This article argues that transparency is best understood as a theory of communication that excessively simplifies and thus is blind to the complexities of the contemporary state, government information, and the public. Taking them fully into account, the article argues, should lead us to question the state’s ability to control information, which in turn should make us question not only the improbability of the state making itself visible, but also the improbability of the state keeping itself secret…(More)”

Chatham House Paper by Michael Edelstein and Dr Jussi Sane: “Political, economic and legal obstacles to data sharing in public health will be the most challenging to overcome.

- The interaction between barriers to data sharing in public health is complex, and single solutions to single barriers are unlikely to be successful. Political, economic and legal obstacles will be the most challenging to overcome.

- Public health data sharing occurs extensively as a collection of subregional and regional surveillance networks. These existing networks have often arisen as a consequence of a specific local public health crisis, and should be integrated into any global framework.

- Data sharing in public health is successful when a perceived need is addressed, and the social, political and cultural context is taken into account.

- A global data sharing legal framework is unlikely to be successful. A global data governance or ethical framework, supplemented by local memoranda of understanding that take into account the local context, is more likely to succeed.

- The International Health Regulations (IHR) should be considered as an infrastructure for data sharing. However, their lack of enforcement mechanism, lack of minimum data sets, lack of capacity assessment mechanism, and potential impact on trade and travel following data sharing need to be addressed.

- Optimal data sharing does not equate with open access for public health data….(More)”

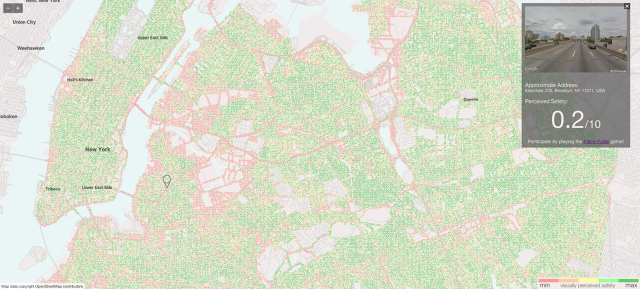

Now, that data is being used to predict what parts of cities feel the safest. StreetScore, a collaboration between the MIT Media Lab’s Macro Connections and Camera Culture groups, uses an algorithm to create a super high-resolution map of urban perceptions. The algorithmically generated data could one day be used to research the connection between urban perception and crime, as well as informing urban design decisions.

The algorithm, created by Nikhil Naik, a Ph.D. student in the Camera Culture lab, breaks an image down into its composite features—such as building texture, colors, and shapes. Based on how Place Pulse volunteers rated similar features, the algorithm assigns the streetscape a perceived safety score between 1 and 10. These scores are visualized as geographic points on a map, designed by MIT rising sophomore Jade Philipoom. Each image available from Google Maps in the two cities are represented by a colored dot: red for the locations that the algorithm tags as unsafe, and dark green for those that appear safest. The site, now limited to New York and Boston, will be expanded to feature Chicago and Detroit later this month, and eventually, with data collected from a new version of Place Pulse, will feature dozens of cities around the world….(More)”

Paper by Frank Mols et al in the European Journal of Political Research: “Policy makers can use four different modes of governance: ‘hierarchy’, ‘markets’, ‘networks’ and ‘persuasion’. In this article, it is argued that ‘nudging’ represents a distinct (fifth) mode of governance. The effectiveness of nudging as a means of bringing about lasting behaviour change is questioned and it is argued that evidence for its success ignores the facts that many successful nudges are not in fact nudges; that there are instances when nudges backfire; and that there may be ethical concerns associated with nudges. Instead, and in contrast to nudging, behaviour change is more likely to be enduring where it involves social identity change and norm internalisation. The article concludes by urging public policy scholars to engage with the social identity literature on ‘social influence’, and the idea that those promoting lasting behaviour change need to engage with people not as individual cognitive misers, but as members of groups whose norms they internalise and enact. …(Also)”

New paper by Shoshana Zuboff in the Journal of Information Technology: “This article describes an emergent logic of accumulation in the networked sphere, ‘surveillance capitalism,’ and considers its implications for ‘information civilization.’ Google is to surveillance capitalism what General Motors was to managerial capitalism. Therefore the institutionalizing practices and operational assumptions of Google Inc. are the primary lens for this analysis as they are rendered in two recent articles authored by Google Chief Economist Hal Varian. Varian asserts four uses that follow from computer-mediated transactions: ‘data extraction and analysis,’ ‘new contractual forms due to better monitoring,’ ‘personalization and customization,’ and ‘continuous experiments.’ An examination of the nature and consequences of these uses sheds light on the implicit logic of surveillance capitalism and the global architecture of computer mediation upon which it depends. This architecture produces a distributed and largely uncontested new expression of power that I christen: ‘Big Other.’ It is constituted by unexpected and often illegible mechanisms of extraction, commodification, and control that effectively exile persons from their own behavior while producing new markets of behavioral prediction and modification. Surveillance capitalism challenges democratic norms and departs in key ways from the centuries long evolution of market capitalism….(More)”

“Open Knowledge today announced plans to develop Open Trials, an open, online database of information about the world’s clinical research trials funded by The Laura and John Arnold Foundation. The project, which is designed to increase transparency and improve access to research, will be directed by Dr. Ben Goldacre, an internationally known leader on clinical transparency.

Open Trials will aggregate information from a wide variety of existing sources in order to provide a comprehensive picture of the data and documents related to all trials of medicines and other treatments around the world. Conducted in partnership with the Center for Open Science and supported by the Center’s Open Science Framework, the project will also track whether essential information about clinical trials is transparent and publicly accessible so as to improve understanding of whether specific treatments are effective and safe.

“There have been numerous positive statements about the need for greater transparency on information about clinical trials, over many years, but it has been almost impossible to track and audit exactly what is missing,” Dr. Goldacre, the project’s Chief Investigator and a Senior Clinical Research Fellow in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine at the University of Oxford, explained. “This project aims to draw together everything that is known around each clinical trial. The end product will provide valuable information for patients, doctors, researchers, and policymakers—not just on individual trials, but also on how whole sectors, researchers, companies, and funders are performing. It will show who is failing to share information appropriately, who is doing well, and how standards can be improved.”

Patients, doctors, researchers, and policymakers use the evidence from clinical trials to make informed decisions about which treatments are best. But studies show that roughly half of all clinical trial results are not published, with positive results published twice as often as negative results. In addition, much of the important information about the methods and findings of clinical trials is only made available outside the normal indexes of academic journals….

Open Trials will help to automatically identify which trial results have not been disclosed by matching registry data on trials that have been conducted against documents containing trial results. This will facilitate routine public audit of undisclosed results. It will also improve discoverability of other documents around clinical trials, which will be indexed and, in some cases, hosted. Lastly, it will help improve recruitment for clinical trials by making information and commentary on ongoing trials more accessible….(More)”

Mo Ibrahim in the Financial Times: “As finance ministers gather this week in Washington DC they cannot but agree and commit to fighting extreme poverty. All of us must rejoice in the fact that over the past 15 years, the world has reportedly already “halved the number of poor people living on the planet”.

But none of us really knows it for sure. It could be less, it could be more. In fact, for every crucial issue related to human development, whether it is poverty, inequality, employment, environment or urbanization, there is a seminal crisis at the heart of global decision making – the crisis of poor data.

Because the challenges are huge and the resources scarce, on these issues more maybe than anywhere else, we need data, to monitor the results and adapt the strategies whenever needed. Bad data feed bad management, weak accountability, loss of resources and, of course, corruption.

It is rather bewildering that while we live in this technology-driven age, the development communities and many of our African governments are relying too much on guesswork. Our friends in the development sector and our African leaders would not dream of driving their cars or flying without instruments. But somehow they pretend they can manage and develop countries without reliable data.

The development community must admit it has a big problem. The sector is relying on dodgy data sets. Take the data on extreme poverty. The data we have are mainly extrapolations of estimates from years back – even up to a decade or more ago. For 38 out of 54 African countries, data on poverty and inequality are either out-dated or non-existent. How can we measure progress with such a shaky baseline? To make things worse we also don’t know how much countries spend on fighting poverty. Only 3 per cent of African citizens live in countries where governmental budgets and expenditures are made open, according to the Open Budget Index. We will never end extreme poverty if we don’t know who or where the poor are, or how much is being spent to help them.

Our African countries have all fought and won their political independence. They should now consider the battle for economic sovereignty, which begins with the ownership of sound and robust national data: how many citizens, living where, and how, to begin with.

There are three levels of intervention required.

First, a significant increase in resources for credible, independent, national statistical institutions. Establishing a statistical office is less eye-catching than building a hospital or school but data driven policy will ensure that more hospital and schools are delivered more effectively and efficiently. We urgently need these boring statistical offices. In 2013, out of a total aid budget of $134.8bn, a mere $280m went in support of statistics. Governments must also increase the resources they put into data.

Second, innovative means of collecting data. Mobile phones, geocoding, satellites and the civic engagement of young tech-savvy citizens to collect data can all secure rapid improvements in baseline data if harnessed.

Third, everyone must take on this challenge of the global public good dimension of high quality open data. Public registers of the ownership of companies, global standards on publishing payments and contracts in the extractives sector and a global charter for open data standards will help media and citizens to track corruption and expose mismanagement. Proposals for a new world statistics body – “Worldstat” – should be developed and implemented….(More)”

Chapter by Kazjon Grace et al in Design Computing and Cognition ’14: “Crowdsourcing design has been applied in various areas of graphic design, software design, and product design. This paper draws on those experiences and research in diversity, creativity and motivation to present a process model for crowdsourcing experience design. Crowdsourcing experience design for volunteer online communities serves two purposes: to increase the motivation of participants by making them stakeholders in the success of the project, and to increase the creativity of the design by increasing the diversity of expertise beyond experts in experience design. Our process model for crowdsourcing design extends the meta-design architecture, where for online communities is designed to be iteratively re-designed by its users. We describe how our model has been deployed and adapted to a citizen science project where nature preserve visitors can participate in the design of a system called NatureNet. The major contribution of this paper is a model for crowdsourcing experience design and a case study of how we have deployed it for the design and development of NatureNet….(More)”