Stefaan Verhulst

New paper by Victor Naroditskiy, Nicholas R. Jennings, Pascal Van Hentenryck, Manuel Cebrian: “Crowdsourcing offers unprecedented potential for solving tasks efficiently by tapping into the skills of large groups of people. A salient feature of crowdsourcing—its openness of entry—makes it vulnerable to malicious behavior. Such behavior took place in a number of recent popular crowdsourcing competitions. We provide game-theoretic analysis of a fundamental tradeoff between the potential for increased productivity and the possibility of being set back by malicious behavior. Our results show that in crowdsourcing competitions malicious behavior is the norm, not the anomaly—a result contrary to the conventional wisdom in the area. Counterintuitively, making the attacks more costly does not deter them but leads to a less desirable outcome. These findings have cautionary implications for the design of crowdsourcing competitions…(More)”

Waldo Jaquith at US Open Data: “Today we’re releasing Let Me Get That Data For You (LMGTDFY), a free, open source tool that quickly and automatically creates a machine-readable inventory of all the data files found on a given website.

When government agencies create an open data repository, they need to start by inventorying the data that the agency is already publishing on their website. This is a laborious process. It means searching their own site with a query like this:

site:example.gov filetype:csv OR filetype:xls OR filetype:json

Then they have to read through all of the results, download all of the files, and create a spreadsheet that they can load into their repository. It’s a lot of work, and as a result it too often goes undone, resulting in a data repository that doesn’t actually contain all of that government‘s data.

Realizing that this was a common problem, we hired Silicon Valley Software Group to create a tool to automate the inventorying process. We worked with Dan Schultz and Ted Han, who created a system built on Django and Celery, using Microsoft’s great Bing Search API as its data source. The result is a free, installable tool, which produces a CSV file that lists all CSV, XML, JSON, XLS, XLSX, XML, and Shapefiles found on a given domain name.

We use this tool to power our new Let Me Get That Data For You website. We’re trying to keep our site within Bing’s free usage tier, so we’re limiting results to 300 datasets per site….(More)”

New Paper by Wlodarczak, Peter and Ally, Mustafa and Soar, Jeffrey: “Opinion mining has rapidly gained importance due to the unprecedented amount of opinionated data on the Internet. People share their opinions on products, services, they rate movies, restaurants or vacation destinations. Social Media such as Facebook or Twitter has made it easier than ever for users to share their views and make it accessible for anybody on the Web. The economic potential has been recognized by companies who want to improve their products and services, detect new trends and business opportunities or find out how effective their online marketing efforts are. However, opinion mining using social media faces many challenges due to the amount and the heterogeneity of the available data. Also, spam or fake opinions have become a serious issue. There are also language related challenges like the usage of slang and jargon on social media or special characters like smileys that are widely adopted on social media sites.

These challenges create many interesting research problems such as determining the influence of social media on people’s actions, understanding opinion dissemination or determining the online reputation of a company. Not surprisingly opinion mining using social media has become a very active area of research, and a lot of progress has been made over the last years. This article describes the current state of research and the technologies that have been used in recent studies….(More)”

Jenny Marder at PBS Newshour: “….Marshall is a worker for Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, an online job forum where “requesters” post jobs, and an army of crowdsourced workers complete them, earning fantastically small fees for each task. The work has been called microlabor, and the jobs, known as Human Intelligence Tasks, or HITs, range wildly. Some are tedious: transcribing interviews or cropping photos. Some are funny: prank calling someone’s buddy (that’s worth $1) or writing the title to a pornographic movie based on a collection of dirty screen grabs (6 cents). And others are downright bizarre. One task, for example, asked workers to strap live fish to their chests and upload the photos. That paid $5 — a lot by Mechanical Turk standards….

These aren’t obscure studies that Turkers are feeding. They span dozens of fields of research, including social, cognitive and clinical psychology, economics, political science and medicine. They teach us about human behavior. They deal in subjects like energy conservation, adolescent alcohol use, managing money and developing effective teaching methods.

….In 2010, the researcher Joseph Henrich and his team published a paper showing that an American undergraduate was about 4,000 times more likely than an average American to be the subject of a research study.

But that output pales in comparison to Mechanical Turk workers. The typical “Turker” completes more studies in a week than the typical undergraduate completes in a lifetime. That’s according to research by Rand, who surveyed both groups. Among those he surveyed, he found that the median traditional lab subject had completed 15 total academic studies — an average of one per week. The median Turker, on the other hand, had completed 300 total academic studies — an average of 20 per week….(More)”

Tanvi Misra at CityLab: “Jokubas Neciunas was looking to buy an apartment almost two years back in Vilnius, Lithuania. He consulted real estate platforms and government data to help him decide the best option for him. In the process, he realized that there was a lot of information out there, but no one was really using it very well.

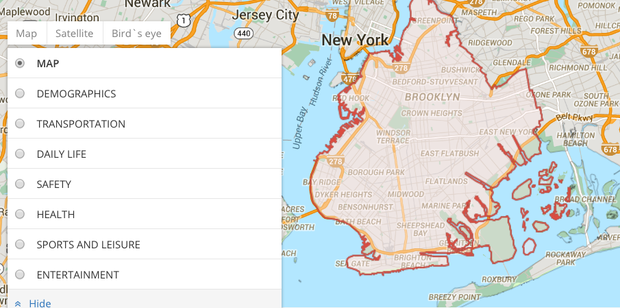

Fast-forward two years, and Neciunas and his colleagues have created PlaceILive.com—a start-up trying to leverage open data from cities and information from social media to create a holistic, accessible tool that measures the “livability” of any apartment or house in a city.

“Smart cities are the ones that have smart citizens,” says PlaceILive co-founder Sarunas Legeckas.

The team recognizes that foraging for relevant information in the trenches of open data might not be for everyone. So they tried to “spice it up” by creating a visually appealing, user-friendly portal for people looking for a new home to buy or rent. The creators hope PlaceILive becomes a one-stop platform where people find ratings on every quality-of-life metric important to them before their housing hunt begins.

In its beta form, the site features five cities—New York, Chicago, San Francisco, London and Berlin. Once you click on the New York portal, for instance, you can search for the place you want to know about by borough, zip code, or address. I pulled up Brooklyn….The index is calculated using a variety of public information sources (from transit agencies, police departments, and the Census, for instance) as well as other available data (from the likes of Google, Socrata, and Foursquare)….(More)”

Hannah Moss at GovLoop: “Government is often perceived as being behind the digital innovation curve, taking significantly longer to adopt web-based solutions than the private sector, with less enthusiasm and less skill. But in recent years, federal, state, and local agencies are challenging that perception. Creating and optimizing digital services has become a top priority for government.

The pressures forcing this change are varied. From the public, we hear calls for heightened transparency, accessibility, and user experience in government services. Internally, government sees digital governance as a way to cut costs and increase efficiency without deteriorating customer service.

But no matter the incentive, government is transforming. Now the question is, “How are public sector organizations going to catch up with, and possibly even surpass, the private sector’s digital progress?”

In the next few years, we see five major trends — many of which have already become a standard component of our interactions with private organizations — dominating government’s digital strategies. These are citizen-centric design, mobility, open source, information as a service, and innovative marketing. In our guide, The Future of Digital Services, we:

- Explore these five trends that are guiding the transition to web-based services.

- Discuss the challenges of digital governance with public and private sector leaders.

- Highlight examples of digital innovation in federal, state, and local governments.

- Provide guidance and resources to help agencies get started on digital initiatives….(More)”

Anna Scott in The Guardian:”Bananas are a staple food in Uganda. Ugandans eat more of the fruit than any other country in the world. Each person eats on average 700g (about seven small bananas) a day, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute, and they provide up to 27% of the population’s calorie intake.

But since 2002 a disease known as banana bacterial wilt (BBW) has wiped out crops across the country. When plants are infected, they cannot absorb water so their leaves start to shrivel and they eventually die….

The Ugandan government drew upon open data – data that is licensed and made available for anyone to access and share – about the disease made available by Unicef’s community polling project Ureport to deal with the problem.

Ureport mobilises a network of nearly 300,000 volunteers across Uganda, who use their mobiles to report on issues that affect them, from polio immunisation to malaria treatment, child marriage, to crop failure. It gathers data from via SMS polls and publishes the results as open sourced, open datasets.

The results are sent back to community members via SMS along with treatment options and advice on how best to protect their crops. Within five days of the first SMS being sent out, 190,000 Ugandans had learned about the disease and knew how to save bananas on their farms.

Via the Ureport platform, the datasets can also be accessed in real-time by community members, NGOs and the Ugandan government, allowing them to target treatments to where they we needed most. They are also broadcast on radio shows and analysed in articles produced by Ureport, informing wider audiences of scope and nature of the disease and how best to avoid it….

A report published this week by the Open Data Institute (ODI) features stories from around the world which reflect how people are using open date in development. Examples range from accessing school results in Tanzania to building smart cities in Latin America….(More).”

Jeff Kelly Lowenstein at StoryBench: “In 2009, while at The Chicago Reporter, I took a deep look at racial disparities in the quality of care in nursing homes in Chicago, Illinois and nationally. For a project that the Center for Public Integrity published in November 2014, I brought together Medicaid cost reports, self-reported staffing figures, testimonies from advocates and lawyers, and personal stories from nursing home residents and their families to address a simple question: how much care is a loved one actually receiving at a nursing home? The conclusion? Nursing homes serving minorities offer a lot less care than those predominately housing whites. …(More)”

Stephen Marche in the New York Times: “….Every month brings fresh figuration to the sprawling, shifting Hieronymus Bosch canvas of faceless 21st-century contempt. Faceless contempt is not merely topical. It is increasingly the defining trait of topicality itself. Every day online provides its measure of empty outrage.

When the police come to the doors of the young men and women who send notes telling strangers that they want to rape them, they and their parents are almost always shocked, genuinely surprised that anyone would take what they said seriously, that anyone would take anything said online seriously. There is a vast dissonance between virtual communication and an actual police officer at the door. It is a dissonance we are all running up against more and more, the dissonance between the world of faces and the world without faces. And the world without faces is coming to dominate…..

The Gyges effect, the well-noted disinhibition created by communications over the distances of the Internet, in which all speech and image are muted and at arm’s reach, produces an inevitable reaction — the desire for impact at any cost, the desire to reach through the screen, to make somebody feel something, anything. A simple comment can so easily be ignored. Rape threat? Not so much. Or, as Mr. Nunn so succinctly put it on Twitter: “If you can’t threaten to rape a celebrity, what is the point in having them?”

The challenge of our moment is that the face has been at the root of justice and ethics for 2,000 years. The right to face an accuser is one of the very first principles of the law, described in the “confrontation clause” of the Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution, but reaching back through English common law to ancient Rome. In Roman courts no man could be sentenced to death without first seeing his accuser. The precondition of any trial, of any attempt to reconcile competing claims, is that the victim and the accused look each other in the face.

For the great French-Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, the encounter with another’s face was the origin of identity — the reality of the other preceding the formation of the self. The face is the substance, not just the reflection, of the infinity of another person. And from the infinity of the face comes the sense of inevitable obligation, the possibility of discourse, the origin of the ethical impulse.

The connection between the face and ethical behavior is one of the exceedingly rare instances in which French phenomenology and contemporary neuroscience coincide in their conclusions. A 2009 study by Marco Iacoboni, a neuroscientist at the Ahmanson-Lovelace Brain Mapping Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, explained the connection: “Through imitation and mimicry, we are able to feel what other people feel. By being able to feel what other people feel, we are also able to respond compassionately to other people’s emotional states.” The face is the key to the sense of intersubjectivity, linking mimicry and empathy through mirror neurons — the brain mechanism that creates imitation even in nonhuman primates.

The connection goes the other way, too. Inability to see a face is, in the most direct way, inability to recognize shared humanity with another. In a metastudy of antisocial populations, the inability to sense the emotions on other people’s faces was a key correlation. There is “a consistent, robust link between antisocial behavior and impaired recognition of fearful facial affect. Relative to comparison groups, antisocial populations showed significant impairments in recognizing fearful, sad and surprised expressions.” A recent study in the Journal of Vision showed that babies between the ages of 4 months and 6 months recognized human faces at the same level as grown adults, an ability which they did not possess for other objects. …

The neurological research demonstrates that empathy, far from being an artificial construct of civilization, is integral to our biology. And when biological intersubjectivity disappears, when the face is removed from life, empathy and compassion can no longer be taken for granted.

The new facelessness hides the humanity of monsters and of victims both. Behind the angry tangles of wires, the question is, how do we see their faces again?

(More)”

“The Agile Government Handbook is a community project to help government learn and adopt Agile development practices….

- Improvement in investment manageability and budgetary feasibility

- Reduction of overall risk

- Frequent delivery of usable capabilities that provide value to customers more rapidly

- Increased flexibility

- Creation of new opportunities for small businesses

- Greater visibility into contractor performance

(Source: The TechFAR Handbook for Procuring Digital Services Using Agile Processes)…