Stefaan Verhulst

Paper by Heiko Richter: “The tremendous rate of technological advancement in recent years has fostered a policy de-bate about improving the state’s access to privately held data (‘B2G data sharing’). Access to such ‘data of general interest’ can significantly improve social welfare and serve the common good. At the same time, expanding the state’s access to privately held data poses risks. This chapter inquires into the potential and limits of mandatory access rules, which would oblige private undertakings to grant access to data for specific purposes that lie in the public interest. The article discusses the key questions that access rules should address and develops general principles for designing and implementing such rules. It puts particular emphasis on the opportunities and limitations for the implementation of horizontal B2G access frameworks. Finally, the chapter outlines concrete recommendations for legislative reforms….(More)”.

2020 Edelman Trust Barometer Spring Update: “… a stunning rise in the public’s trust in government and business. Since January, trust in government has risen nine points and trust in business has risen six points, underscoring the fact that now more than ever, U.S. business must take the lead. This is particularly important because while trust in government has risen sharply in a few short months, the government in the U.S. is still distrusted overall, with approval of only 48%. Overall, business trust has surged to 56% over the same period.

This significant shift in sentiment marks a once-in-a-century moment for business to step forward. This is especially important given the fact that historically our research shows that considerable increases in trust scores are often be followed by losses in trust.

This opportunity for business is particularly important because half of respondents maintain that business needs to take a lead in providing economic relief and support, and 60 percent say that CEOs should take the lead on pandemic response as opposed to waiting for the government to impose it. That said, only 27% say CEOs are doing an outstanding job meeting the demands placed on them by the pandemic.

For corporate leaders, this is a moment of reckoning—and a time for radical transparency. It is imperative for corporate leaders to be open, direct and frequent about the measures they’re taking to balance public health and the economy and protect employee and customer safety. Our survey shows that CEOs have an amazing opportunity to lead their own organizations on this front right now, with a 10 point increase among U.S. respondents since March to tell the truth about the pandemic.

And to understand just how high the stakes are for business leaders to get things right, 54% of U.S. respondents are very concerned about job loss due to the pandemic and not being able to find a new job for a very long time. This occurs at a time when only 37% of U.S. respondents believe business is doing well or very well at protecting their employees’ financial wellbeing and safeguarding their jobs.

Our data also shows that only 41% of Americans think business is doing “well or very well” at ensuring the products and services that people need most are readily available and easily accessible. But the data also shows there is more opportunity for business to offer ingenuity—in the form of new market entrants and strategic pivots. Now is a time for clients to sharpen their strategic planning, in line with the ways Covid-19 is changing their audiences.

Our survey also uncovers a sense of underlying optimism that business leaders must tap into in order to positively transition out of the current situation. As horrible as the pandemic is, 64% of U.S. respondents believe this will lead to valuable innovations and changes for the better in how we live, work and treat each other as people…(More)”

Paper by Olivier Bargain and Ulugbek Aminjonov: “While degraded trust and cohesion within a country are often shown to have large socioeconomic impacts, they can also have dramatic consequences when compliance is required for collective survival. We illustrate this point in the context of the COVID-19 crisis. Policy responses all over the world aim to reduce social interaction and limit contagion.

Using data on human mobility and political trust at regional level in Europe, we examine whether the compliance to these containment policies depends on the level of trust in policy makers prior to the crisis. Using a double difference approach around the time of lockdown announcements, we find that high-trust regions decrease their mobility related to non-necessary activities significantly more than low-trust regions. We also exploit country and time variation in treatment using the daily strictness of national policies. The efficiency of policy stringency in terms of mobility reduction significantly increases with trust. The trust effect is nonlinear and increases with the degree of stringency. We assess how the impact of trust on mobility potentially translates in terms of mortality growth rate..(More)”.

Survey by FTI Consulting: “…reported significant increases in spend and data privacy-related programs. Though respondents are increasing their emphasis on privacy compliance, the results showed that many are also willing to take risks in the interest of tapping into the value of their data. Still others believe that “good faith” efforts will improve their position with regulators. Key findings include:

- 97 percent of organizations will increase their spend on data privacy in the coming year, with nearly one-third indicating plans to increase budgets by between 90 percent and more than 100 percent.

- 78 percent agreed with the statement: “The value of data is encouraging organizations to find ways to avoid complying fully with data privacy regulation.”

- 87 percent of respondents believed that steps toward compliance will mitigate regulatory scrutiny. More than half strongly agreed with this idea.

- 44 percent said they expect lack of awareness and training to be the key data privacy challenge of the coming year.

In terms of solutions, respondents indicated a diverse array of techniques for the coming year, and only 6 percent said they had no plans for change. The top-rated solutions set for implementation over the next 12 months included establishing a clear, consistent set of data privacy standards, updating agreements and contracts with external parties, reviewing standard data privacy practices of supply chains and building privacy-by-design programs….(More)”.

Simon Horobin at The Conversation: “Language always tells a story. As COVID-19 shakes the world, many of the words we’re using to describe it originated during earlier calamities – and have colourful tales behind them.

In the Middle Ages, for example, fast-spreading infectious diseases were known as plagues – as in the Bubonic plague, named for the characteristic swellings (or buboes) that appear in the groin or armpit. With its origins in the Latin word plaga meaning “stroke” or “wound”, plague came to refer to a wider scourge through its use to describe the ten plagues suffered by the Egyptians in the biblical book of Exodus.

An alternative term, pestilence, derives from Latin pestis (“plague”), which is also the origin of French peste, the title of the 1947 novel by Albert Camus (La Peste, or The Plague) which has soared up the bestseller charts in recent weeks. Latin pestis also gives us pest, now used to describe animals that destroy crops, or any general nuisance or irritant. Indeed, the bacterium that causes Bubonic plague is called Yersinia pestis….

The later plagues of the 17th century led to the coining of the word epidemic. This came from a Greek word meaning “prevalent”, from epi “upon” and demos “people”. The more severe pandemic is so called because it affects everyone (from Greek pan “all”).

A more recent coinage, infodemic, a blend of info and epidemic, was introduced in 2003 to refer to the deluge of misinformation and fake news that accompanied the outbreak of SARS (an acronym formed from the initial letters of “severe acute respiratory syndrome”).

The 17th-century equivalent of social distancing was “avoiding someone like the plague”. According to Samuel Pepys’s account of the outbreak that ravaged London in 1665, infected houses were marked with a red cross and had the words “Lord have mercy upon us” inscribed on the doors. Best to avoid properties so marked….(More)”.

Article by Virginia Barbour and Martin Borchert: “In the few months since the first case of COVID-19 was identified, the underlying cause has been isolated, its symptoms agreed on, its genome sequenced, diagnostic tests developed, and potential treatments and vaccines are on the horizon. The astonishingly short time frame of these discoveries has only happened through a global open science effort.

The principles and practices underpinning open science are what underpin good research—research that is reliable, reproducible, and has the broadest impact possible. It specifically requires the application of principles and practices that make research FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable); researchers are making their data and preliminary publications openly accessible, and then publishers are making the peer-reviewed research immediately and freely available to all. The rapid dissemination of research—through preprints in particular as well as journal articles—stands in contrast to what happened in the 2003 SARS outbreak when the majority of research on the disease was published well after the outbreak had ended.

Many outside observers might reasonably assume, given the digital world we all now inhabit, that science usually works like this. Yet this is very far from the norm for most research. Science is not something that just happens in response to emergencies or specific events—it is an ongoing, largely publicly funded, national and international enterprise….

Sharing of the underlying data that journal articles are based on is not yet a universal requirement for publication, nor are researchers usually recognised for data sharing.

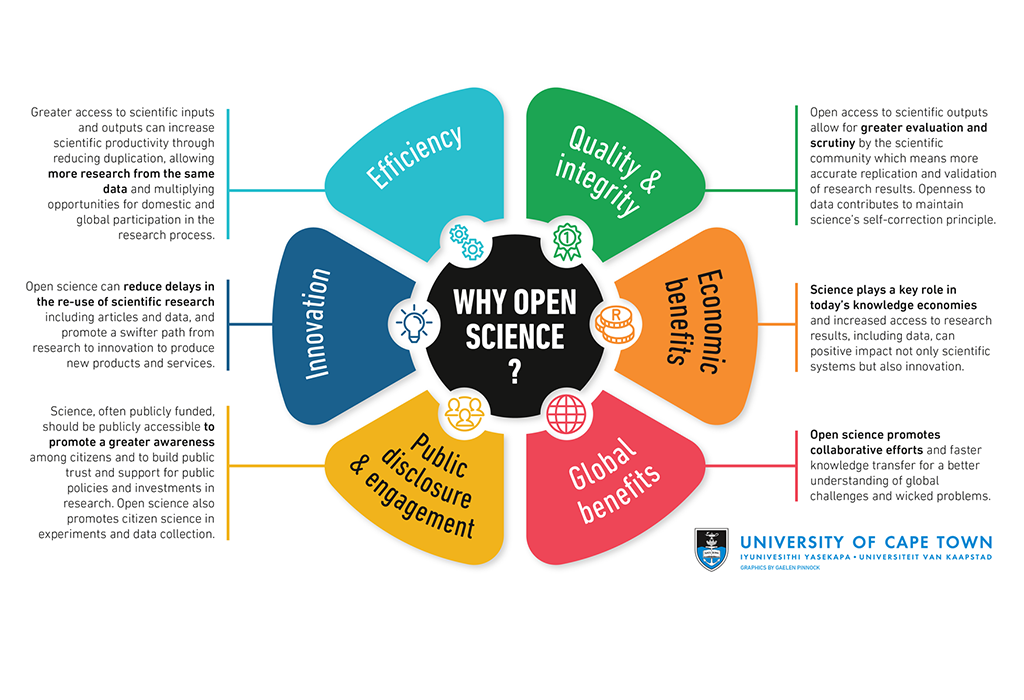

There are many benefits associated with an open science model. Image adapted from: Gaelen Pinnock/UCT; CC-BY-SA 4.0 .

Once published, even access to research is not seamless. The majority of academic journals still require a subscription to access. Subscriptions are expensive; Australian universities alone currently spend more than $300 million per year on subscriptions to academic journals. Access to academic journals also varies between universities with varying library budgets. The main markets for subscriptions to the commercial journal literature are higher education and health, with some access to government and commercial….(More)”.

Article by Peter Baeck and Sophie Reynolds: One of the most prominent examples of how technology and data is being used to empower citizens is happening in Seoul. Here the city has used its ‘citizens as mayors’ philosophy for smart cities; an approach which aims to equip citizens with the same real-time access to information as the mayor. Seoul has gone further than most cities in making information about the COVID-19 outbreak in the city accessible to citizens. Its dashboard is updated multiple times daily and allows citizens to access the latest anonymised information on confirmed patients’ age, gender and dates of where they visited and when, after developing symptoms. Citizens can access even more detailed information; down to visited restaurants and cinema seat numbers.

The goal is to provide citizens with the information needed to take precautionary measures, self-monitor and report if they start showing symptoms after visiting one of the “infection points.” To help allay people’s fears and reduce the stigma associated with businesses that have been identified as “infection points”, the city government also provides citizens with information about the nearest testing clinics and makes “clean zones” (places that have been disinfected after visits by confirmed patients) searchable for users.

In addition to national and institutional responses there are (at least) five ways collective intelligence approaches are helping city governments, companies and urban communities in the fight against COVID-19:

1. Open sharing with citizens about the spread and management of COVID-19:

Based on open data provided by public agencies, private sector companies are using the city as a platform to develop their own real-time dashboards and mobile apps to further increase public awareness and effectively disseminate disease information. This has been the case with Corona NOW, Corona Map, Corona 100m in Seoul, Korea – which allow people to visualise data on confirmed coronavirus patients, along with patients’ nationality, gender, age, which places the patient has visited, and how close citizens are to these coronavirus patients. Developer Lee Jun-young who created the Corona Map app, said he built it because he found that the official government data was too difficult to understand.

Meanwhile in city state Singapore, the dashboard developed by UpCode scrapes data provided by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s own dashboard (which is exceptionally transparent about coronavirus case data) to make it cleaner and easier to navigate, and vastly more insightful. For instance, it allows you to learn about the average recovery time for those infected.

UpCode is making its platform available for others to re-use in other contexts.

2. Mobilising community-led responses to tackle COVID-19

Crowdfunding is being used in a variety of ways to get short-term targeted funding to a range of worthy causes opened up by the COVID-19 crisis. Examples include helping to fundraise for community activities for those directly affected by the crisis, backing tools and products that can address the crisis (such as buying PPE) and pre-purchasing products and services from local shops and artists. A significant proportion of the UK’s 1,000 plus mutual aid initiatives are now turning to crowdfunding as a way to rapidly respond to the new and emerging needs occurring at the city-wide and hyperlocal (i.e. streets and neighbourhood) levels.

Aberdeen City Mutual Aid group set up a crowdfunded community fund to cover the costs of creating a network of volunteers across the city, as well as any expenses incurred at food shops, fuel costs for deliveries and purchasing other necessary supplies. Similarly, the Feed the Heroes campaign was launched with an initial goal of raising €250 to pay for food deliveries for frontline staff who are putting in extra hours at the Mater Hospital, Dublin during the coronavirus outbreak….(More)”.

Bryan Wolff, Yevheniia Berchul, Yu Gong, Andrey Shevlyakov at Strelka Mag: “French philosopher Michel Foucault defined biopower as the power over bodies, or the social and political techniques to control people’s lives. Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe continued this line of thinking to arrive at necropolitics, the politics of death, or as he phrases it: “contemporary forms of subjugation of life, to the power of death.” COVID-19 has put these powers in sharp relief. Most world-changing events of the twenty-first century have been internalized with the question “where were you?” For example, “where were you when the planes hit?” But the pandemic knows no single universal moment to refer to. It’s become as much a question of when, as of where. “When did you take the pandemic seriously?” Most likely, your answer stands in direct relation to your proximity to death. Whether a critical mass or a specific loss, fatality defined COVID-19’s reality.

For many governments, it wasn’t the absolute count of death, but rather its simulations that made them take action. The United States was one of the last countries holding out on a lockdown until the Imperial College report projected the possibility of two million to four million fatalities in the US alone (if no measures were taken). And these weren’t the only simulations being run. A week into the lockdown, it was wondered aloud whether this was all worth the cost. It was a unique public reveal of the deadly economics—or necroeconomics—that we’re usually insulated from, whether through specialist language games or simply because they’re too grim to face. But ignoring the financialization of our demise doesn’t make it go away. If we are to ever reconsider the systems meant to keep us alive, we’d better get familiar. What better place to start than to see the current crisis through the eyes of one of the most widely used models of death: the one that puts a price on life. It’s called the “Value of a Statistical Life” or VSL..(More)”.

Mariana Mazzucato and Giulio Quaggiotto at Project Syndicate: “Decades of privatization, outsourcing, and budget cuts in the name of “efficiency” have significantly hampered many governments’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis. At the same time, successful responses by other governments have shown that investments in core public-sector capabilities make all the difference in times of emergency. The countries that have handled the crisis well are those where the state maintains a productive relationship with value creators in society, by investing in critical capacities and designing private-sector contracts to serve the public interest.

From the United States and the United Kingdom to Europe, Japan, and South Africa, governments are investing billions – and, in some cases, trillions – of dollars to shore up national economies. Yet, if there is one thing we learned from the 2008 financial crisis, it is that quality matters at least as much as quantity. If the money falls on empty, weak, or poorly managed structures, it will have little effect, and may simply be sucked into the financial sector. Too many lives are at stake to repeat past errors.

Unfortunately, for the last half-century, the prevailing political message in many countries has been that governments cannot – and therefore should not – actually govern. Politicians, business leaders, and pundits have long relied on a management creed that focuses obsessively on static measures of efficiency to justify spending cuts, privatization, and outsourcing.

As a result, governments now have fewer options for responding to the crisis, which may be why some are now desperately clinging to the unrealistic hope of technological panaceas such as artificial intelligence or contact-tracing apps. With less investment in public capacity has come a loss of institutional memory (as the UK’s government has discovered) and increased dependence on private consulting firms, which have raked in billions. Not surprisingly, morale among public-sector employees has plunged in recent years.

Consider two core government responsibilities during the COVID-19 crisis: public health and the digital realm. In 2018 alone, the UK government outsourced health contracts worth £9.2 billion ($11.2 billion), putting 84% of beds in care homes in the hands of private-sector operators (including private equity firms). Making matters worse, since 2015, the UK’s National Health Service has endured £1 billion in budget cuts.

Outsourcing by itself is not the problem. But the outsourcing of critical state capacities clearly is, especially when the resulting public-private “partnerships” are not designed to serve the public interest. Ironically, some governments have outsourced so eagerly that they have undermined their own ability to structure outsourcing contracts. After a 12-year effort to spur the private sector to develop low-cost ventilators, the US government is now learning that outsourcing is not a reliable way to ensure emergency access to medical equipment….(More)”.

Seth Reynolds at NPC: “Never has the interdependence of our world been experienced by so many, so directly, so rapidly and so simultaneously. Our response to one threat, Covid-19, has unleashed a deluge of secondary and tertiary consequences that have swept across the globe faster than the virus itself. The butterfly effect has taken on new dimensions, as the reality of system interdependence at multiple levels has been brought directly into our homes and news feeds:

- Individually, an innocuous bus journey sends a stranger to intensive care in a fortnight

- Societally, health charities are warning that actions taken in response to one health crisis – Covid-19 – could lead to up to 11,000 deaths of women in childbirth around the world because of another – namely, 9.5m women not getting access to family planning intervention.

- Governmentally, some systemic consequences of decision-making are there for all to see, while others are less immediately apparent – for example, Trump’s false proclamation of testing availability “for anyone that wants one” ended up actually reducing the availability of tests by immediately increasing demand. It even reduced the already scarce supply of protective masks, which must be disposed of after testing.

Students will be studying coronavirus for years. A systems lens can help us learn essential lessons. Covid-19 has provided many clear examples of effective systemic action, and stark lessons in the consequences of non-systemic thinking. Leaders and decision-makers everywhere are being compelled to think broader and deeper about causation and consequence. Decisions taken, even words spoken, without systemic awareness can have – indeed have had – profoundly damaging effects.

Systemic thinking, planning, action and leadership must now be mainstreamed – individually, organisationally, societally, across public, private and charity sectors. As one American diplomat recently reflected: “from climate change to the coronavirus, complex adaptive systems thinking is key to handling crises”. In fact, some epidemiologists, suddenly the world’s most valuable profession, have been calling for more systemic ways of working for years. However, we currently do not think and act in accordance with how our complex systems function and this has been part of the Covid-19 problem…(More)”.