Stefaan Verhulst

Paper by Steven M. Bellovin, Preetam K. Dutta and Nathan Reitinger: “Sharing is a virtue, instilled in us from childhood. Unfortunately, when it comes to big data — i.e., databases possessing the potential to usher in a whole new world of scientific progress — the legal landscape prefers a hoggish motif. The historic approach to the resulting database–privacy problem has been anonymization, a subtractive technique incurring not only poor privacy results, but also lackluster utility. In anonymization’s stead, differential privacy arose; it provides better, near-perfect privacy, but is nonetheless subtractive in terms of utility.

Today, another solution is leaning into the fore, synthetic data. Using the magic of machine learning, synthetic data offers a generative, additive approach — the creation of almost-but-not-quite replica data. In fact, as we recommend, synthetic data may be combined with differential privacy to achieve a best-of-both-worlds scenario. After unpacking the technical nuances of synthetic data, we analyze its legal implications, finding both over and under inclusive applications. Privacy statutes either overweigh or downplay the potential for synthetic data to leak secrets, inviting ambiguity. We conclude by finding that synthetic data is a valid, privacy-conscious alternative to raw data, but is not a cure-all for every situation. In the end, computer science progress must be met with proper policy in order to move the area of useful data dissemination forward….(More)”.

Darrell West at Brookings: “Though digital technology has transformed nearly every corner of the economy in recent years, the health care industry seems stubbornly immune to these trends. That may soon change if more wearable devices record medical information that physicians can use to diagnose and treat illnesses at earlier stages. Last month, Apple announced that an FDA-approved electrocardiograph (EKG) will be included in the latest generation Apple Watch to check the heart’s electrical activity for signs of arrhythmia. However, the availability of this data does not guarantee that health care providers are currently equipped to process all of it. To cope with growing amounts of medical data from wearable devices, health care providers may need to adopt artificial intelligence that can identify data trends and spot any deviations that indicate illness. Greater medical data, accompanied by artificial intelligence to analyze it, could expand the capabilities of human health care providers and offer better outcomes at lower costs for patients….

By 2016, American health care spending had already ballooned to 17.9 percent of GDP. The rise in spending saw a parallel rise in health care employment. Patients still need doctors, nurses, and health aides to administer care, yet these health care professionals might not yet be able to make sense of the massive quantities of data coming from wearable devices. Doctors already spend much of their time filling out paperwork, which leaves less time to interact with patients. The opportunity may arise for artificial intelligence to analyze the coming flood of data from wearable devices. Tracking small changes as they happen could make a large difference in diagnosis and treatment: AI could detect abnormal heartbeat, respiration, or other signs that indicate worsening health. Catching symptoms before they worsen may be key to improving health outcomes and lowering costs….(More)”.

Paper by A.K. Njeru, B. Malakwen and M. Lumala in the International Academic Journal of Social Sciences and Education: “Throughout history information is a key factor in conflict management around the world. The media can play its important role of being the society’s watch dog of the society, by exposing to the masses what is essential but hidden, however the same media may also be used to mobilize masses to violence. Social media can therefore act as a tool for widening the democratic space, but can also lead to destabilization of peace.

The aim of the study was to establish the challenges facing social media platforms in conflict prevention in Kenya since 2007: a case of Ushahidi platform in Kenya. The paradigm that was found suitable for this study is Pragmatism. The study used a mixed approach. In this study, interviews, focus group discussions and content analysis of the Ushahidi platform were chosen as the tools of data collection. In order to bring order, structure and interpretation to the collected data, the researcher systematically organized the data by coding it into categories and constructing matrixes. After classifying the data, the researcher compared and contrasted it to the information retrieved from the literature review.

The study found that One major weak point social media as a tool for conflict prevention is the lack of ethical standards and professionalism for the users. It is too liberal and thus can be used to spread unverified information and distorted facts that might be detrimental to peace building and conflict prevention. This has led to some of the users already questioning the credibility of the information that is circulated through social media. The other weak point about social media as tool for peace building is that it is dependent to a major extent on the access to internet. The availability of internet in low units doesn’t necessarily mean cheap access. So over time the high cost of internet might affect the efficiency of the social media as a tool. The study concluded that information credibility is essential if social media as a tool is to be effective in conflict prevention and peace building.

The nature of social media which allows for anonymity of identity gives room for unverified information to be floated around the social media networks; this can be detrimental to the conflict prevention and peace building initiatives. There is therefore need for information verification and authentication by a trusted agent, to offer information appertaining to violence, conflict prevention and peace building on the social media platforms. The study recommends that Ushahidi platform should be seen as an agent of social change and should discuss the social mobilization which may be able to bring about. The study further suggest that if we can look at Ushahidi platform as a development agent, can we then take this a step further and ask, or try to find, a methodology that looks at the Ushahidi platform as peacemaking agent, or to assist in the maintenance of peace in a post-conflict thereby tapping into Ushahidi platform’s full potential….(More)”.

Nouriel Roubini at Project Syndicate: “Blockchain has been heralded as a potential panacea for everything from poverty and famine to cancer. In fact, it is the most overhyped – and least useful – technology in human history.

In practice, blockchain is nothing more than a glorified spreadsheet. But it has also become the byword for a libertarian ideology that treats all governments, central banks, traditional financial institutions, and real-world currencies as evil concentrations of power that must be destroyed. Blockchain fundamentalists’ ideal world is one in which all economic activity and human interactions are subject to anarchist or libertarian decentralization. They would like the entirety of social and political life to end up on public ledgers that are supposedly “permissionless” (accessible to everyone) and “trustless” (not reliant on a credible intermediary such as a bank).

Yet far from ushering in a utopia, blockchain has given rise to a familiar form of economic hell. A few self-serving white men (there are hardly any women or minorities in the blockchain universe) pretending to be messiahs for the world’s impoverished, marginalized, and unbanked masses claim to have created billions of dollars of wealth out of nothing. But one need only consider the massive centralization of power among cryptocurrency “miners,” exchanges, developers, and wealth holders to see that blockchain is not about decentralization and democracy; it is about greed….

As for blockchain itself, there is no institution under the sun – bank, corporation, non-governmental organization, or government agency – that would put its balance sheet or register of transactions, trades, and interactions with clients and suppliers on public decentralized peer-to-peer permissionless ledgers. There is no good reason why such proprietary and highly valuable information should be recorded publicly.

Moreover, in cases where distributed-ledger technologies – so-called enterprise DLT – are actually being used, they have nothing to do with blockchain. They are private, centralized, and recorded on just a few controlled ledgers. They require permission for access, which is granted to qualified individuals. And, perhaps most important, they are based on trusted authorities that have established their credibility over time. All of which is to say, these are “blockchains” in name only.

It is telling that all “decentralized” blockchains end up being centralized, permissioned databases when they are actually put into use. As such, blockchain has not even improved upon the standard electronic spreadsheet, which was invented in 1979.1

No serious institution would ever allow its transactions to be verified by an anonymous cartel operating from the shadows of the world’s authoritarian kleptocracies. So it is no surprise that whenever “blockchain” has been piloted in a traditional setting, it has either been thrown in the trash bin or turned into a private permissioned database that is nothing more than an Excel spreadsheet or a database with a misleading name….(More)”.

Interview with Paul Tucker by Benedict King: “In your book, you place what you call the “administrative state” at the heart of the political dilemmas facing the liberal political order. Could you tell us what you mean by ‘the administrative state’ and the dilemmas it poses for democratic societies?

This is about the legitimacy of the structure of government that has developed in Western democracies. The ‘administrative state’ is simply the machinery for implementing policy and law. What matters is that much of it—including many regulators and central banks—is no longer under direct ministerial control. They are not part of a ministerial department. They are not answerable day-to-day, minute-by-minute to the prime minister or, in other countries, the president.

When I was young, in Europe at least, these arm’s-length agencies were a small part of government, but now they are a very big part. Over here, that transformation has come about over the past thirty-odd years, since the 1990s, whereas in America it goes back to the 1880s, and especially the 1930s New Deal reforms of President Roosevelt.

“The ‘administrative state’ is simply the machinery for implementing policy and law. ”

In the United Kingdom we used to call these agencies ‘quangos’, but that acronym trivialises the issue. Today, many—in the US, probably most—of the laws to which businesses and even individuals are subject are written and enforced by regulatory agencies, part of the administrative state, rather than passed by Parliament or Congress and enforced by the elected executive. That would surprise John Locke, Montesquieu and James Madison, who developed the principles associated with the separation of powers and constitutionalism.

To some extent, these changes were driven by a perceived need to turn to ‘expertise’. But the effect has been to shift more of our government away from our elected representatives and to unelected technocrats. An underlying premise at the heart of my book (although not something that I can prove) is that, since any and every part of government eventually fails—and may fail very badly, as we saw with the collapse of the financial system in 2008—there is a risk that people will get fed up with this shift to governance by unelected experts. The people will get fed up with their lives being affected so much by people who they didn’t have a chance to vote for and can’t vote out. If that happened, it would be dangerous as the genius of representative democracy is that it separates how we as citizens feel about the system of government from how we feel about the government of the day. So how can we avoid that without losing the benefits of delegation? That is what the debate about the administrative state is ultimately about: its dryness belies its importance to how we govern ourselves.

“The genius of representative democracy is that it separates how we as citizens feel about the system of government from how we feel about the government of the day”

It matters, therefore, that the array of agencies in the administrative state varies enormously in the degree to which they are formally insulated from politics. My book Unelected Power is about ‘independent agencies’, by which I mean an agency that is insulated day-to-day from both the legislative branch (Parliament or Congress) and also from the executive branch of government (the prime minister or president). Central banks are the most important example of such independent agencies in modern times, wielding a wide range of monetary and regulatory powers….(More + selection of five books to read)”.

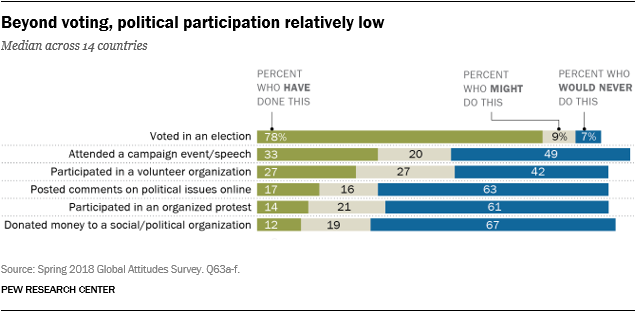

Richard Wike and Alexandra Castillo at Pew Research Center: “An engaged citizenry is often considered a sign of a healthy democracy. High levels of political and civic participation increase the likelihood that the voices of ordinary citizens will be heard in important debates, and they confer a degree of legitimacy on democratic institutions. However, in many nations around the world, much of the public is disengaged from politics.

To better understand public attitudes toward civic engagement, Pew Research Center conducted face-to-face surveys in 14 nations encompassing a wide range of political systems. The study, conducted in collaboration with the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) as part of their International Consortium on Closing Civic Space (iCon), includes countries from Africa, Latin America, Europe, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Because it does not represent every region, the study cannot reflect the globe as a whole. But with 14,875 participants across such a wide variety of countries, it remains a useful snapshot of key, cross-national patterns in civic life.

The survey finds that, aside from voting, relatively few people take part in other forms of political and civic participation. Still, some types of engagement are more common among young people, those with more education, those on the political left and social network users. And certain issues – especially health care, poverty and education – are more likely than others to inspire political action. Here are eight key takeaways from the survey, which was conducted from May 20 to Aug. 12, 2018, via face-to-face interviews.

Most people vote, but other forms of participation are much less common. Across the 14 nations polled, a median of 78% say they have voted at least once in the past. Another 9% say they might vote in the future, while 7% say they would never vote.

With at least 9-in-10 reporting they have voted in the past, participation is highest in three of the four countries with compulsory voting (Brazil, Argentina and Greece). Voting is similarly high in both Indonesia (91%) and the Philippines (91%), two countries that do not have compulsory voting laws.

The lowest percentage is found in Tunisia (62%), which has only held two national elections since the Jasmine Revolution overthrew long-serving President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 2011 and spurred the Arab Spring protests across the Middle East.

Attending a political campaign event or speech is the second most common type of participation among those surveyed – a median of 33% have done this at least once. Fewer people report participating in volunteer organizations (a median of 27%), posting comments on political issues online (17%), participating in an organized protest (14%) or donating money to a social or political organization (12%)….(More)”.

Rebecca Elliott at Work in Progress: “Climate change is making the planet we inhabit a more dangerous place to live. After the devastating 2017 hurricane season in the U.S. and Caribbean, it has become easier, and more frightening, to comprehend what a world of more frequent and severe storms and extreme weather might portend for our families and communities.

When policymakers, officials, and experts talk about such threats, they often do so in a language of “value at risk”: a measurement of the financial worth of assets exposed to potential losses in the face of natural hazards. This language is not only descriptive, expressing the extent of the threat, it is also in some ways prescriptive.

Information about value and risk provides a way for us to exert some control, to “tame uncertainty” and, if not precisely predict, at least to plan and prepare prudently for the future. If we know the value at risk, we can take smart steps to protect it.

This logic can, however, break down in practice.

After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, I went to New York City to find out how residents there, particularly homeowners, were responding to a new landscape of “value at risk.” In the wake of the catastrophe, they had received a new “flood insurance rate map” that expanded the boundaries of the city’s high-risk flood zones.

129 billion dollars of property was now officially “at risk” of flood, an increase of more than 120 percent over the previous map.

And yet, I found that many New Yorkers were less worried about the threat of flooding than they were about the flood map itself. As one Rockaway man put it, the map was “scarier than another storm.”

Far from producing clear strategies of action, the map produced ambivalent actors and outcomes. Even when people took steps to reduce their flood risk, they often did not feel that they were better off or more secure for having done so. How can we understand this?

By examining the social life of the flood insurance rate map, talking to its users (affected residents as well as the experts, officials, and professionals who work with them), I found that the stakes on the ground were bigger than just property values and floods. Other kinds of values were threatened here, and not just from floods, complicating the decision of what to do and when….(More)”.

Anni Rowland-Campbell at NPC: “In his book The Code Economy Philip E. Auerswald talks about the long history of humans developing codeas a mechanism by which to create and regulate activities and markets.[1] We have Codes of Practice, Ethical Codes, Building Codes, and Legal Codes, just to name a few.

Each and every one of these is based on the data of human behaviour, and that data can now be collected, analysed, harvested and repurposed as never before through the application of intelligent machines that operate and are instructed by algorithms. Anything that can be articulated as an algorithm—a self-contained sequence of actions to be performed—is now fertile ground for machine analysis, and increasingly machine activity.

So, what does this mean for us humans who, are ourselves a conglomeration of DNA code? I have spent many years thinking about this. Not that long ago my friends and family tolerated my speculations with good humour, but a fair degree of scepticism. Now I run workshops for boards and even my children are listening far more intently. Because people are sensing that the invasion of the ‘Social Machine’ is changing our relationship with such things as privacy, as well as with both ourselves and each other. It is changing how we understand our role as humans.

The Social Machine is the name given to the systems we have created that blur the lines between computational processes and human input, of which the World Wide Web is the largest and best known example. These ‘smart machines’ are increasingly pervading almost every aspect of human existenceand, in many ways, getting to know us better than we know ourselves.

So who stands up for us humans? Who determines how society will harness and utilise the power of information technologies whilst ensuring that the human remain both relevant and important?…

Philanthropists must equip themselves with the knowledge they need in order to do good with digital

Consider the Luddites as they smashed the looms in the early 1800s. Their struggle is instructive because they were amongst the first to experience technological displacement. They sensed the degradation of human kind and they fought for social equality and fairness in the distribution of the benefits of science and technology to all. If knowledge is power, philanthropy must arm itself with knowledge of digital to ensure the power of digital lies with the many and not the few.

The best place to start in understanding the digital world as it stands now is to begin to see the world, and all human activities, through the lens of data and as a form of digital currency. This links back to the earlier idea of codes. Our activities, up until recently, were tacit and experiential, but now they are becoming increasingly explicit and quantified. Where we go, who we meet, what we say, what we do is all being registered, monitored and measured as long as we are connected to the digital infrastructure.

A new currency is emerging that is based on the world’s most valuable resource: data. It is this currency that connects the arteries and capillaries, and reaches across all disciplines and fields of expertise. The kind of education that is required now is to be able to make connections and to see the opportunities in the interstice between policy and day-to-day reality.

The dominant players in this space thus far have been the large corporations and governments that have harnessed and exploited digital currencies for their own benefit. Shoshana Zuboff describes this as the ‘surveillance economy’. But this data actually belongs to each and every human who generates it. As people begin to wake up to this we are gradually realising that this is what fuels the social currency of entrepreneurship, leadership and innovation, and provides the legitimacy upon which trust is based.

Trust is an outcome of experiences and interactions, but governments and corporations have transactionalised their interactions with citizens and consumer through exploiting data. As a consequence they have eroded the esteem with which they are held. The more they try to garner greater insights through data and surveillance, the more they alienate the people they seek to reach.

If we are smart what we need to do, as philanthropists, is to understand the fundamentals of data as a currency and integrate this in to each and every interaction we have. This will enable us to create relationships with the people that are based on the authenticity of purpose, supported by the data of proof. Yes, there have been some instances where the sector has not done as well as it could and betrayed that trust. But this only serves as a lesson as to how fragile the world of trust and legitimacy are. It shows how crucial it is that we define all that we do in terms of social outcomes and impact, however that is defined….(More)”

This book introduces the concept of smart city as the potential solution to the challenges created by urbanization. The Internet of Things (IoT) offers novel features with minimum human intervention in smart cities. This book describes different components of Internet of Things (IoT) for smart cities including sensor technologies, communication technologies, big data analytics and security….(More)”.

Report by Michael A. Weber for the Congressional Research Service: “Widespread concerns exist among analysts and policymakers over the current trajectory of democracy around the world. Congress has often played an important role in supporting and institutionalizing U.S. democracy promotion, and current developments may have implications for U.S. policy, which for decades has broadly reflected the view that the spread of democracy around the world is favorable to U.S. interests.

The aggregate level of democracy around the world has not advanced for more than a decade. Analysis of data trendlines from two major global democracy indexes indicates that, as of 2017, the level of democracy around the world has not advanced since around the year 2005 or 2006. Although the degree of democratic backsliding around the world has arguably been modest overall to this point, some elements of democracy, particularly those associated with liberal democracy, have receded during this period. Declines in democracy that have occurred may have disproportionately affected countries with larger population sizes. Overall, this data indicates that democracy’s expansion has been more challenged during this period than during any similar period dating back to the 1970s. Despite this, democratic declines to this point have been considerably less severe than the more pronounced setbacks that occurred during some earlier periods in the 20th century.

Numerous broad factors may be affecting democracy globally. These include (but are not limited to) the following:

- The growing international influence of nondemocratic governments. These countries may in some instances view containing the spread of democracy as instrumental toward other goals or as helpful to their own domestic regime stability. Thus they may be engaging in various activities that have negative impacts on democracy internationally. At the same time, relatively limited evidence exists to date of a more affirmative agenda to promote authoritarian political systems or norms as competing alternatives to democracy.

- The state of democracy’s global appeal as a political system. Challenges to and apparent dissatisfaction with government performance within democracies, and the concomitant emergence of economically successful authoritarian capitalist states, may be affecting in particular democracy’s traditional instrumental appeal as the political system most capable of delivering economic growth and national prestige. Public opinion polling data indicate that democracy as a political system may overall still retain considerable appeal around the world relative to nondemocratic alternatives.

- Nondemocratic governments’ use of new methods to repress political dissent within their own societies. Tools such as regulatory restrictions on civil society and technology-enhanced censorship and surveillance are arguably enhancing the long-term durability of nondemocratic forms of governance.

- Structural conditions in nondemocracies. Some scholars argue that broad conditions in many of the world’s remaining nondemocracies, such as their level of wealth or economic inequality, are not conducive to sustained democratization. The importance of these factors to democratization is complex and contested among experts.

Democracy promotion is a longstanding, but contested, element of U.S. foreign policy. Wide disagreements and wellworn policy debates persist among experts over whether, or to what extent, the United States should prioritize democracy promotion in its foreign policy. Many of these debates concern the relevance of democracy promotion to U.S. interests, its potential tension with other foreign policy objectives, and the United States’ capacity to effectively promote democratization.

Recent developments pose numerous potential policy considerations and questions for Congress. Democracy promotion has arguably not featured prominently in the Trump Administration’s foreign policy to this point, creating potential continued areas of disagreement between some Members of Congress and the Administration. Simultaneously, current challenges around the world present numerous questions of potential consideration for Congress. Broadly, these include whether and where the United States should place greater or lesser emphasis on democracy promotion in its foreign policy, as well as various related questions concerning the potential tools for promoting democracy…(More)”.