Stefaan Verhulst

Book edited by Giovanni Schiuma and Daniela Carlucci: “As digital technologies occupy a more central role in working and everyday human life, individual and social realities are increasingly constructed and communicated through digital objects, which are progressively replacing and representing physical objects. They are even shaping new forms of virtual reality. This growing digital transformation coupled with technological evolution and the development of computer computation is shaping a cyber society whose working mechanisms are grounded upon the production, deployment, and exploitation of big data. In the arts and humanities, however, the notion of big data is still in its embryonic stage, and only in the last few years, have arts and cultural organizations and institutions, artists, and humanists started to investigate, explore, and experiment with the deployment and exploitation of big data as well as understand the possible forms of collaborations based on it.

Big Data in the Arts and Humanities: Theory and Practice explores the meaning, properties, and applications of big data. This book examines therelevance of big data to the arts and humanities, digital humanities, and management of big data with and for the arts and humanities. It explores the reasons and opportunities for the arts and humanities to embrace the big data revolution. The book also delineates managerial implications to successfully shape a mutually beneficial partnership between the arts and humanities and the big data- and computational digital-based sciences.

Big data and arts and humanities can be likened to the rational and emotional aspects of the human mind. This book attempts to integrate these two aspects of human thought to advance decision-making and to enhance the expression of the best of human life….(More)“.

Robert Foyle Hunwick at The New Republic: China’s “social credit system”, which becomes mandatory in 2020, aims to funnel all behavior into a credit score….The quoted text is from a 2014 State Council resolution which promises that every involuntary participant will be rated according to their “commercial sincerity,” “social security,” “trust breaking” and “judicial credibility.”

Some residents welcome it. Decades of political upheaval and endemic corruption has bred widespread mistrust; most still rely on close familial networks (guanxi) to get ahead, rather than public institutions. An endemic lack of trust is corroding society; frequent incidents of “bystander effect”—people refusing to help injured strangers for fear of being held responsible—have become a national embarrassment. Even the most enthusiastic middle-class supporters of the ruling Communist Party (CCP) feel perpetually insecure. “Fraud has become ever more common,” Lian Weiliang, vice chairman of the CCP’s National Development and Reform Commission, recently admitted. “Swindlers must pay a price.”

The solution, apparently, lies in a data-driven system that automatically separates the good, the bad, and the ugly…

once compulsory state “social credit” goes national in 2020, these shadowy algorithms will become even more opaque. Social credit will align with Communist Party policy to become another form of law enforcement. Since Beijing relaxed its One Child Policy to cope with an aging population (400 million seniors by 2035), the government has increasingly indulged in a form of nationalist natalism to encourage more two-child families. Will women be penalized for staying single, and rewarded for swapping their careers for childbirth? In April, one of the country’s largest social-media companies banned homosexual content from its Weibo platform in order to “create a bright and harmonious community environment” (the decision was later rescinded in favor of cracking down on all sexual content). Will people once again be forced to hide non-normative sexual orientations in order to maintain their rights? An investigation by the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab also warns that social credit policies would be used to discourage protest.

State media has defended social credit against Orwellian charges, arguing that China’s maturing economy requires a “well-functioning” apparatus like the U.S.’s FICO credit score system. But, counters Lubman, “the U.S. systems, maintained by three companies, collect only financially related information.” In the UK, citizens are entitled to an Equifax report itemizing their credit status. In China, only the security services have access to an individual’s dang’an, the personal file containing every scrap of information the state keeps on them, from exam results to their religious and political views….(More)”.

Sarah Elizabeth Richards at Smithsonian: “We live in the age of big DNA data. Scientists are eagerly sequencing millions of human genomes in the hopes of gleaning information that will revolutionize health care as we know it, from targeted cancer therapies to personalized drugs that will work according to your own genetic makeup.

There’s a big problem, however: the data we have is too white. The vast majority of participants in worldwide genomics research are of European descent. This disparity could potentially leave out minorities from benefitting from the windfall of precision medicine. “It’s hard to tailor treatments for people’s unique needs, if the people who are suffering from those diseases aren’t included in the studies,” explains Jacquelyn Taylor, associate professor in nursing who researches health equity at New York University.

That’s about to change with the “All of Us” initiative, an ambitious health research endeavor by the National Institutes of Health that launches in May. Originally created in 2015 under President Obama as the Precision Medicine Initiative, the project aims to collect data from at least 1 million people of all ages, races, sexual identities, income and education levels. Volunteers will be asked to donate their DNA, complete health surveys and wear fitness and blood pressure trackers to offer clues about the interplay of their stats, their genetics and their environment….(More)”.

Rohan Pearce at Computerworld – Australia: “A new position of the ‘National Data Commissioner’ will be established as part of a $65 million, four-year open data push by the federal government.

The creation of the new position is part of the government’s response to the Productivity Commission inquiry into the availability and use of public and private data by individuals and organisations.

The government in November revealed that it would legislate a new Consumer Data Right as part of its response to the PC’s recommendations. The government said that this will allow individuals to access data relating to their banking, energy, phone and Internet usage, potentially making it easier to compare and switch between service providers.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission will have oversight of the Consumer Data Right.

The government said today it would introduce a new data sharing and release framework to streamline the way government data is made available for use by researchers and public and private sector organisations.

The framework’s aim will be to promote the greater use of data and drive related economic and innovation benefits as well as to “Build trust with the Australian community about the government’s use of data”.

The government said it would push a risk-based approach to releasing publicly funded data sets.

The National Data Commissioner will be supported by a National Data Advisory Council. The council “will advise the National Data Commissioner on ethical data use, technical best practice, and industry and international developments.”…(More).

Saskia Brechenmacher and Thomas Carothers at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: “Civil society is under stress globally as dozens of governments across multiple regions are reducing space for independent civil society organizations, restricting or prohibiting international support for civic groups, and propagating government-controlled nongovernmental organizations. Although civic activists in most places are no strangers to repression, this wave of anti–civil society actions and attitudes is the widest and deepest in decades. It is an integral part of two broader global shifts that raise concerns about the overall health of the international liberal order: the stagnation of democracy worldwide and the rekindling of nationalistic sovereignty, often with authoritarian features.

Attacks on civil society take myriad forms, from legal and regulatory measures to physical harassment, and usually include efforts to delegitimize civil society. Governments engaged in closing civil society spaces not only target specific civic groups but also spread doubt about the legitimacy of the very idea of an autonomous civic sphere that can activate and channel citizens’ interests and demands. These legitimacy attacks typically revolve around four arguments or accusations:

- That civil society organizations are self-appointed rather than elected, and thus do not represent the popular will. For example, the Hungarian government justified new restrictions on foreign-funded civil society organizations by arguing that “society is represented by the elected governments and elected politicians, and no one voted for a single civil organization.”

- That civil society organizations receiving foreign funding are accountable to external rather than domestic constituencies, and advance foreign rather than local agendas. In India, for example, the Modi government has denounced foreign-funded environmental NGOs as “anti-national,” echoing similar accusations in Egypt, Macedonia, Romania, Turkey, and elsewhere.

- That civil society groups are partisan political actors disguised as nonpartisan civic actors: political wolves in citizen sheep’s clothing. Governments denounce both the goals and methods of civic groups as being illegitimately political, and hold up any contacts between civic groups and opposition parties as proof of the accusation.

- That civil society groups are elite actors who are not representative of the people they claim to represent. Critics point to the foreign education backgrounds, high salaries, and frequent foreign travel of civic activists to portray them as out of touch with the concerns of ordinary citizens and only working to perpetuate their own privileged lifestyle.

Attacks on civil society legitimacy are particularly appealing for populist leaders who draw on their nationalist, majoritarian, and anti-elite positioning to deride civil society groups as foreign, unrepresentative, and elitist. Other leaders borrow from the populist toolbox to boost their negative campaigns against civil society support. The overall aim is clear: to close civil society space, governments seek to exploit and widen existing cleavages between civil society and potential supporters in the population. Rather than engaging with the substantive issues and critiques raised by civil society groups, they draw public attention to the real and alleged shortcomings of civil society actors as channels for citizen grievances and demands.

The widening attacks on the legitimacy of civil society oblige civil society organizations and their supporters to revisit various fundamental questions: What are the sources of legitimacy of civil society? How can civil society organizations strengthen their legitimacy to help them weather government attacks and build strong coalitions to advance their causes? And how can international actors ensure that their support reinforces rather than undermines the legitimacy of local civic activism?

To help us find answers to these questions, we asked civil society activists working in ten countries around the world—from Guatemala to Tunisia and from Kenya to Thailand—to write about their experiences with and responses to legitimacy challenges. Their essays follow here. We conclude with a final section in which we extract and discuss the key themes that emerge from their contributions as well as our own research…

- Saskia Brechenmacher and Thomas Carothers, The Legitimacy Landscape

- César Rodríguez-Garavito, Objectivity Without Neutrality: Reflections From Colombia

- Walter Flores, Legitimacy From Below: Supporting Indigenous Rights in Guatemala

- Arthur Larok, Pushing Back: Lessons From Civic Activism in Uganda

- Kimani Njogu, Confronting Partisanship and Divisions in Kenya

- Youssef Cherif, Delegitimizing Civil Society in Tunisia

- Janjira Sombatpoonsiri, The Legitimacy Deficit of Thailand’s Civil Society

- Özge Zihnioğlu, Navigating Politics and Polarization in Turkey

- Stefánia Kapronczay, Beyond Apathy and Mistrust: Defending Civic Activism in Hungary

- Zohra Moosa, On Our Own Behalf: The Legitimacy of Feminist Movements

- Nilda Bullain and Douglas Rutzen, All for One, One for All: Protecting Sectoral Legitimacy

- Saskia Brechenmacher and Thomas Carothers, The Legitimacy Menu….(More)”.

Vyjayanti Desai at The Worldbank: “…Using a combination of the self-reported figures from country authorities, birth registration and other proxy data, the 2018 ID4D Global Dataset suggests that as many as 1 billion people struggle to prove who they are. The data also revealed that of the 1 billion people without an official proof of identity:

- 81% live in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, indicating the need to scale up efforts in these regions

- 47% are below the national ID age of their country, highlighting the importance of strengthening birth registration efforts and creating a unique, lifetime identity;

- 63% live in lower-middle income economies, while 28% live in low-income economies, reinforcing that lack of identification is a critical concern for the global poor….

In addition, to further strengthen understanding of who the undocumented are and the barriers they face, ID4D partnered with the 2017 Global Findex to gather for the first time this year, nationally-representative survey data from 99 countries on foundational ID coverage, use, and barriers to access. The survey data (albeit limited in its coverage to people aged 15 and older) confirm that the coverage gap is largest in low income countries (LICs), where 38% of the surveyed population does not have a foundational ID. Regionally, sub-Saharan Africa shows the largest coverage gap, where close to one in three people in surveyed countries lack a foundational ID.

Although global gender gaps in foundational ID coverage are relatively small, The countries with the greatest #gender gaps in foundational ID coverage also tend to be those with #legal barriers for women’s access to #identity documents….(More)”.

Matthew Taylor at the RSA: “I have, more or less, chosen the topic for my annual lecture. There’s just one problem. How do I get anyone to take notice?…The lecture will make the case for democratic deliberation to become an integral part of our political and policy making processes. I’ll do this by highlighting just a few of the many problems with our current form of representative democracy (and what is seen as its main alternative, direct democracy). I will argue that not only is deliberation the best way to gauge public preferences on many issues, but that by adding depth to debates and engagement it can help repair the democratic system as a whole. Indeed, deliberation is best seen not as an alternative to elections but as a way of making politics more about representing people and less about the fight between – often deeply unrepresentative – vested interests.

Making democratic deliberation a reality

An important and new aspect of my argument will be to suggest a set of practical measures. These are the policies that would need to be enacted if we wanted to take deliberation from the exotic and occasional margins of policy making instead to make it a recognised, vital and permanent part of how we are governed. For example, one might be that Government commit to holding at least two fully constituted citizens’ juries every year and to the relevant minister making a formal response to each jury’s outcomes in a statement to the House.

My speech may quote the Hansard Society democratic audit published today. This shows, on the one hand, an increase in people’s interest in politics and in their intention to vote but, on the other, very low ratings for the way we are governed and for the trustworthiness and efficacy of political parties; institutions which continue to be central to the way our democracy functions. …

Democratic deliberation is not the same as direct democracy nor is it simply another form of general engagement. It is the use of specific and robust methods to inform representative groups of ordinary citizens so that these citizens, having heard every side of an argument and having had a chance to deliberate, can reach a view which – like a jury in a criminal trial – can stand for the conclusions which would have been reached by any representative group going through the same process. As I will explain in my lecture, these processes have been used successfully on a wide range of issues in a wide variety of jurisdictions. The problem is not about whether deliberation works: it is about how to make it a core part of how we do politics….(More)”.

Hanna Kozlowska and Heather TimmonsNextGov: “Founded in 2001, Wikipedia is on the verge of adulthood. It’s the world’s fifth-most popular website, with 46 million articles in 300 languages, while having less than 300 full-time employees. What makes it successful is the 200,000 volunteers who create it, said Katherine Maher, the executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation, the parent-organization for Wikipedia and its sister sites.

Unlike other tech companies, Wikipedia has avoided accusations of major meddling from malicious actors to subvert elections around the world. Part of this is because of the site’s model, where the creation process is largely transparent, but it’s also thanks to its community of diligent editors who monitor the content…

Somewhat unwittingly, Wikipedia has become the internet’s fact-checker. Recently, both YouTube and Facebook started using the platform to show more context about videos or posts in order to curb the spread of disinformation—even though Wikipedia is crowd-sourced, and can be manipulated as well….

While no evidence of organized, widespread election-related manipulation on the platform has emerged so far, Wikipedia is not free of malicious actors, or people trying to grab control of the narrative. In Croatia, for instance, the local-language Wikipedia was completely taken over by right-wing ideologues several years ago.

The platform has also been battling the problem of “black-hat editing”— done surreptitiously by people who are trying to push a certain view—on the platform for years….

About 200,000 editors contribute to Wikimedia projects every month, and together with AI-powered bots they made a total of 39 million edits in February of 2018. In the chart below, group-bots are bots approved by the community, which do routine maintenance on the site, looking for examples of vandalism, for example. Name-bots are users who have “bot” in their name.

Like every other tech platform, Wikimedia is looking into how AI could help improve the site. “We are very interested in how AI can help us do things like evaluate the quality of articles, how deep and effective the citations are for a particular article, the relative neutrality of an article, the relative quality of an article,” said Maher. The organization would also like to use it to catch gaps in its content….(More)”.

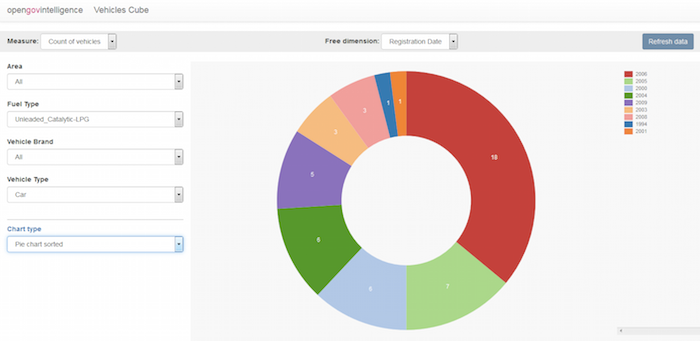

OpenGovIntelligence: “Imagine an executive Government Department that needs to manage resources and make decisions on a daily basis without possessing any data to support them. This is the case in the supervising department of Government Vehicles, which is part of the Greek Ministry of Administrative Reconstruction. This department is in charge of the supervision and management of the whole fleet of Greek Government Vehicles….In an attempt to solve this problem, the Greek Ministry of Administrative Reconstruction joined the OpenGovernmentIntelligence project as a pilot partner to exploit statistical data for this purpose. Preliminary findings of the project team were very encouraging, to the surprise of Greek Ministry executives. There was a plethora of Government Vehicle data owned by other governmental and non-governmental bodies. Interestingly, the Ministry of Transport even had record level data of all vehicles, including governmental ones. Other data providers included the Hellenic Statistical Authority and the Hellenic Association of Motor Vehicle Importers-Representatives that provided fuel consumption and gas emissions data. Even more impressively, before the end of the first year of the project, a new web-based platform was built by means of the OGI toolkit. Its goal was to provide visualisations and statistical metrics to enhance executive decision making. For the first time, decision makers could acquire knowledge on metrics such as the average age, cubic capacity or daily fuel consumptions of a Government Agency fleet.

However, a lot still needs to be done. The primary concern of the Greek Pilot team members is now data quality, as the Ministry of Administrative Reconstruction does not own any of these data. Next steps include data validation and cleansing, as well as collaboration with other agencies serving as intermediates for government fleet management regarding service co-production. Executives in the Greek Ministry of Administrative Reconstruction are now pleased to have access to data that will enhance their ability to make rational decisions regarding Government Vehicles. This is a small, but at the same time essential, step for a country struggling with economic recession….(More)”.