Maria Krisette Capati at Crowdsourcing Week: “We are exposed to a myriad of news and updates worldwide. As the crowd becomes moreinvolved in providing information, adopting that ‘upload mindset’ coined by Will Merritt ofZooppa, access to all kinds of data is a few taps and clicks away….

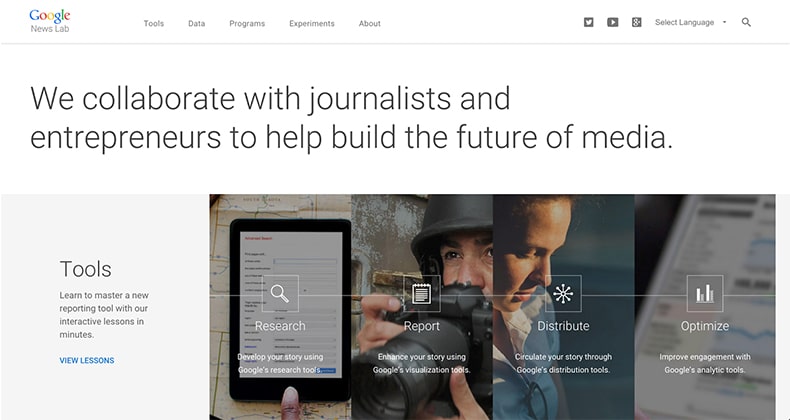

Google News Lab – Better reporting and insightful storytelling

Last week, Google announced its own crowdsourced news platform dubbed News Lab as part of their efforts “to empower innovation at the intersection of technology and media.”

Scouting for real-time stories, updates, and breaking news is much easier and systematize for journalists worldwide. They can use Google’s tools for better reporting, data for insightful storytelling and programs to focus on the future of media, tackling this initiative in three ways.

“There’s a revolution in data journalism happening in newsrooms today, as more data sets and more tools for analysis are allowing journalists to create insights that were never before possible,” Google said.

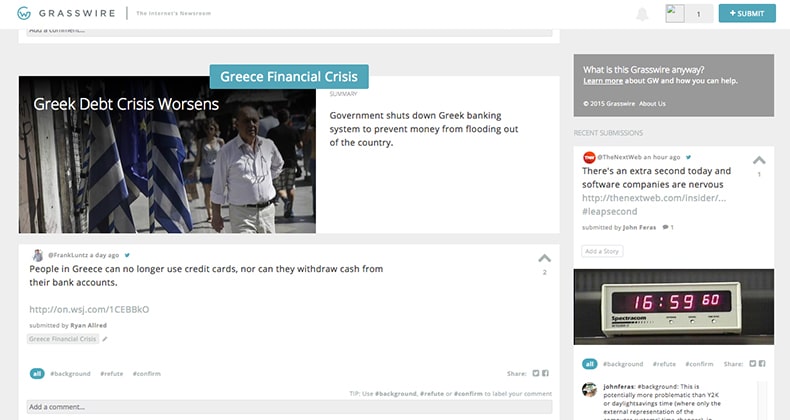

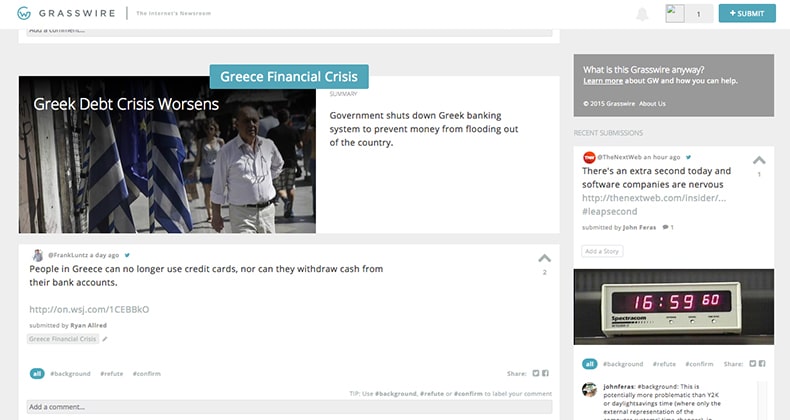

Grasswire – first-hand information in real-time

The design looks bleak and simple, but the site itself is rich with content—first-hand information crowdsourced from Twitter users in real-time and verified. Austen Allred, co-founder of Grasswire was inspired to develop the platform after his “minor slipup” as the American Journalism Review (AJR) puts it, when he missed his train out of Shanghai that actually saved his life.

“The bullet train Allred was supposed to be on collided with another train in the Wenzhou area ofChina’s Zhejiang province,” AJR wrote. “Of the 1,630 passengers, 40 died, and another 210 were injured.” The accident happened in 2011. Unfortunately, the Chinese government made some cover upon the incident, which frustrated Allred in finding first-hand information.

After almost four years, Grasswire was launched, a website that collects real-time information from users for breaking news infused with crowdsourcing model afterward. “It’s since grown into a more complex interface, allowing users to curate selected news tweets by voting and verifying information with a fact-checking system,” AJR wrote, which made the verification of data open and systematized.

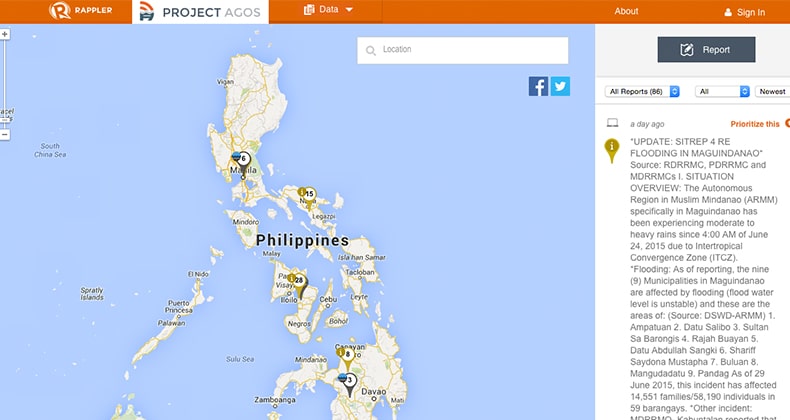

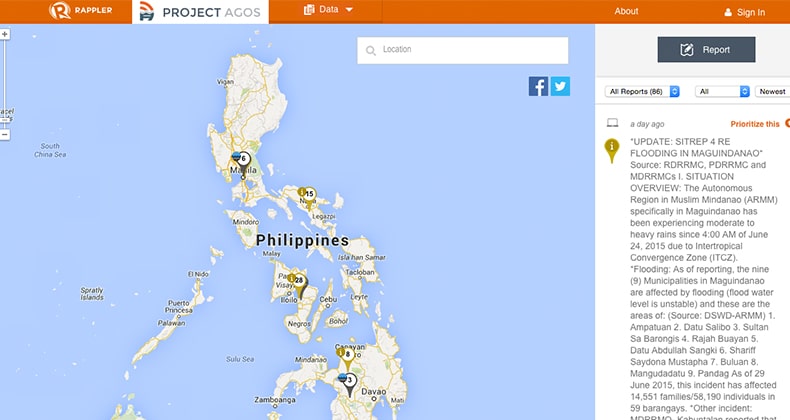

Rappler – Project Agos: a technology for disaster risk reduction

The Philippines is a favorite hub for typhoons. The aftermath of typhoon Haiyan was exceedingly disastrous. But the crowds were steadfast in uploading and sharing information and crowdsourcing became mainstream during the relief operations. Maria Ressa said that they had to educate netizens to use the appropriate hashtags for years (#nameoftyphoonPH, e.g. #YolandaPH) for typhoons to collect data on social media channels easily.

Education and preparation can mitigate the risks and save lives if we utilize the right technology and act accordingly. In her blog, After Haiyan: Crisis management and beyond, Maria wrote, “We need to educate not just the first responders and local government officials, but more importantly, the people in the path of the storms.” …

China’s CCDI app – Crowdsourcing political reports to crack down corruption practices

In China, if you want to mitigate or possible, eradicate corrupt practices, then there’s an app for that.China launched its own anti-corruption app called, Central Commission for Discipline InspectionWebsite App, allowing the public to upload text messages, photos and videos of Chinese officials’ any corrupt practices.

The platform was released by the government agency, Central Committee for Discipline Inspection.Nervous in case you’ll be tracked as a whistleblower? Interestingly, anyone can report anonymously.China Daily said, “the anti-corruption authorities received more than 1,000 public reports, and nearly70 percent were communicated via snapshots, text messages or videos uploaded,” since its released.Kenya has its own version, too, called Ushahidi using crowdmapping, and India’s I Paid a Bribe.

Newzulu – share news, publish and get paid

While journalists can get fresh insights from Google News Labs, the crowd can get real-time verified news from Grasswire, and CCDI is open for public, Newzulu crowdsourced news platforms doesn’t just invite the crowd to share news, they can also publish and get paid.

It’s “a community of over 150,000 professional and citizen journalists who share and break news to the world as it happens,” originally based in Sydney. Anyone can submit stories, photos, videos, and even stream live….(More)”