Stefaan Verhulst

First issue of the Government Oxford Review focusing on trust (or lack of trust) in government:

“In 2016, governments are in the firing line. Their populations suspect them of accelerating globalisation for the benefit of the few, letting trade drive away jobs, and encouraging immigration so as to provide cheaper labour and to fill skills-gaps without having to invest in training. As a result the ‘anti-government’, ‘anti-expert’, ‘anti-immigration’ movements are rapidly gathering support. The Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom, the Presidential run of Donald Trump in the United States, and the Five Star movement in Italy are but three examples.” Dean Ngaire Woods

Our contributors have shed an interesting, and innovative, light on this issue. McKinsey’s Andrew Grant and Bjarne Corydon discuss the importance of transparency and accountability of government, while Elizabeth Linos, from the Behavioural Insights Team in North America, and Princeton’s Eldar Shafir discuss how behavioural science can be utilised to implement better policy, and Geoff Mulgan, CEO at Nesta, provides insights into how harnessing technology can bring about increased collective intelligence.

The Conference Addendum features panel summaries from the 2016 Challenges of Government Conference, written by our MPP and DPhil in Public Policy students.

Lena Groeger at ProPublica: “A few weeks ago, Snapchat released a new photo filter. It appeared alongside many of the other such face-altering filters that have become a signature of the service. But instead of surrounding your face with flower petals or giving you the nose and ears of a Dalmatian, the filter added slanted eyes, puffed cheeks and large front teeth. A number of Snapchat users decried the filter as racist, saying it mimicked a “yellowface” caricature of Asians. The company countered that they meant to represent anime characters and deleted the filter within a few hours.

“Snapchat is the prime example of what happens when you don’t have enough people of color building a product,” wrote Bay Area software engineer Katie Zhu in an essay she wrote about deleting the app and leaving the service. In a tech world that hires mostly white men, the absence of diverse voices means that companies can be blind to design decisions that are hurtful to their customers or discriminatory.A Snapchat spokesperson told ProPublica that the company has recently hired someone to lead their diversity recruiting efforts.

A Snapchat spokesperson told ProPublica that the company has recently hired someone to lead their diversity recruiting efforts.

But this isn’t just Snapchat’s problem. Discriminatory design and decision-making affects all aspects of our lives: from the quality of our health care and education to where we live to what scientific questions we choose to ask. It would be impossible to cover them all, so we’ll focus on the more tangible and visual design that humans interact with every day.

You can’t talk about discriminatory design without mentioning city planner Robert Moses, whose public works projects shaped huge swaths of New York City from the 1930s through the 1960s. The physical design of the environment is a powerful tool when it’s used to exclude and isolate specific groups of people. And Moses’ design choices have had lasting discriminatory effects that are still felt in modern New York.

A notorious example: Moses designed a number of Long Island Parkway overpasses to be so low that buses could not drive under them. This effectively blocked Long Island from the poor and people of color who tend to rely more heavily on public transportation. And the low bridges continue to wreak havoc in other ways: 64 collisions were recorded in 2014 alone (here’s a bad one).

The design of bus systems, railways, and other forms of public transportation has a history riddled with racial tensions and prejudiced policies. In the 1990s the Los Angeles’ Bus Riders Union went to court over the racial inequity they saw in the city’s public transportation system. The Union alleged that L.A.’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority spent “a disproportionately high share of its resources on commuter rail services, whose primary users were wealthy non-minorities, and a disproportionately low share on bus services, whose main patrons were low income and minority residents.” The landmark case was settled through a court-ordered consent decree that placed strict limits on transit funding and forced the MTA to invest over $2 billion in the bus system.

Of course, the design of a neighborhood is more than just infrastructure. Zoning laws and regulations that determine how land is used or what schools children go to have long been used as a tool to segregate communities. All too often, the end result of zoning is that low-income, often predominantly black and Latino communities are isolated from most of the resources and advantages of wealthy white communities….(More)”

Innar Liiv at OXPOL: “How can big data and data science help policy-making? This question has recently gained increasing attention. Both the European Commission and the White House have endorsed the use of data for evidence-based policy making.

Still, a gap remains between theory and practice. In this blog post, I make a number of recommendations for systematic development paths.

RESEARCH TRENDS SHAPING DATA FOR POLICY

‘Data for policy’ as an academic field is still in its infancy. A typology of the field’s foci and research areas are summarised in the figure below.

Besides the ‘data for policy’ community, there are two important research trends shaping the field: 1) computational social science; and 2) the emergence of politicised social bots.

Computational social science (CSS) is an new interdisciplinary research trend in social science, which tries to transform advances in big data and data science into research methodologies for understanding, explaining and predicting underlying social phenomena.

Social science has a long tradition of using computational and agent-based modelling approaches (e.g.Schelling’s Model of Segregation), but the new challenge is to feed real-life, and sometimes even real-time information into those systems to get gain rapid insights into the validity of research hypotheses.

For example, one could use mobile phone call records to assess the acculturation processes of different communities. Such a project would involve translating different acculturation theories into computational models, researching the ethical and legal issues inherent in using mobile phone data and developing a vision for generating policy recommendations and new research hypothesis from the analysis.

Politicised social bots are also beginning to make their mark. In 2011, DARPA solicited research proposals dealing with social media in strategic communication. The term ‘political bot’ was not used, but the expected results left no doubt about the goals…

The next wave of e-government innovation will be about analytics and predictive models. Taking advantage of their potential for social impact will require a solid foundation of e-government infrastructure.

The most important questions going forward are as follows:

- What are the relevant new data sources?

- How can we use them?

- What should we do with the information? Who cares? Which political decisions need faster information from novel sources? Do we need faster information? Does it come with unanticipated risks?

These questions barely scratch the surface, because the complex interplay between general advancements of computational social science and hovering satellite topics like political bots will have an enormous impact on research and using data for policy. But, it’s an important start….(More)”

Springwise: “Just over two years ago, in April 2014, city officials in Flint, Michigan decided to save costs by switching the city’s water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River. Because of the switch, residents of the town and their children were exposed to dangerous levels of lead. Much of the population suffered from the side effects of lead poisoning, including skin lesions, hair loss, depression and anxiety and in severe cases, permanent brain damage. Media attention, although focussed at first, inevitably died down. To avoid future similar disasters, Sean Montgomery, a neuroscientist and the CEO of technology company, Connected Future Labs, set up CitizenSpring.

CitizenSpring is an app which enables individuals to test their water supply using readily available water testing kits. Users hold a test strip underneath running water, hold the strip to a smartphone camera and press the button. The app then reveals the results of the test, also cataloguing the test results and storing them in the cloud in the form of a digital map. Using what Montgomery describes as “computer vision,” the app is able to detect lead levels in a given water source and confirm whether they exceed the Environmental Protection Agency’s “safe” threshold. The idea is that communities can inform themselves about their own and nearby water supplies in order that they can act as guardians of their own health. “It’s an impoverished data problem,” says Montgomery. “We don’t have enough data. By sharing the results of test[s], people can, say, find out if they’re testing a faucet that hasn’t been tested before.”

CitizenSpring narrowly missed its funding target on Kickstarter. However, collective monitoring can work. We have already seen the power of communities harnessed to crowdsource pollution data in the EU and map conflict zones through user-submitted camera footage….(More)”

Adele Peters at FastCo-Exist: “…a new app and proposed political party called MiVote—aims to rethink how citizens participate in governance. Instead of voting only in elections, people using the app can share their views on every issue the government considers. The idea is that parliamentary representatives of the “MiVote party” would commit to support legislation only when it’s in line with the will of the app’s members—regardless of the representative’s own opinion….

Like Democracy Earth, a nonprofit that started in Argentina, MiVote uses the blockchain to make digital voting and identity fully secure. Democracy Earth also plans to use a similar model of representation, running candidates who promise to adhere to the results of online votes rather than a particular ideology.

But MiVote takes a somewhat different approach to gathering opinions. The app will give users a notification when a new issue is addressed in the Australian parliament. Then, voters get access to a digital “information packet,” compiled by independent researchers, that lets them dive into four different approaches.

“We don’t talk about the bill or the legislation at all,” says Jacoby. “If you put it into a business context, the bill or the legislation is the contract. In no business would you write the contract before you know what the deal looks like. If we’re looking for genuine democracy, the bill has to be determined by the people . . . Once we know where the people want to go, then we focus on making sure the bill gets us there.”

If the parliament is going to vote about immigration, for example, you might get details about a humanitarian approach, a border security approach, a financially pragmatic approach, and an approach that focuses on international relations. For each frame of reference, the app lets you dive into as much information as you need to decide. If you don’t read anything, it won’t let you cast a vote.

“We’re much more interested in a solutions-oriented approach rather than an ideological approach,” he says. “Ideology basically says I have the answer for you before you’ve even asked the question. There is no ideology, no worldview, that has the solution to everything that ails us.”

Representatives of this hypothetical new party won’t have to worry about staying on message, because there is no message; the only goal is to vote after the people speak. That might free politicians to focus on solutions rather than their image…(More)”

US Census: “As many kids across the nation go back to school this month, we are excited to roll out a new U.S. Census Bureau program, “Statistics in Schools,” aimed at making a real and positive difference in American education….The new website provides data, tools and teacher-friendly activities to K-12 educators in math, history, and social studies as well as the newly added subjects of geography and sociology. We also doubled the number of tools on the website; resulting in more than 100 resources from which teachers can choose, including:

- Maps and historical documents — historical and current maps as well as photos, cartoons and census records.

- News articles — examples of census data applied to current events in the news. Videos — the importance of statistics and how data relates to students today.

- Games — test your students’ knowledge in our population bracketology game.

- Infographics and data visualizations — census data presented visually; many linked to a classroom activity.

- Searchable data tools that reveal population statistics by sex, age, ethnicity and race.

- Activities organized by grade, education standard and subject.

- Information to help teachers explain the Census Bureau to students….

The next step in the program is perhaps the most exciting, as educators throughout the nation begin to leverage Statistics in Schools to enrich their curricula. I look forward to being on this journey with you and working toward improved statistical literacy for the next generation. Please stay in touch — we will be listening closely to learn what works, what could be improved, and how the Census Bureau can continue to help you….(More)”

Christian Seelos & Johanna Mair at Stanford Social Innovation Review: “Efforts by social enterprises to develop novel interventions receive a great deal of attention. Yet these organizations often stumble when it comes to turning innovation into impact. As a result, they fail to achieve their full potential. Here’s a guide to diagnosing and preventing several “pathologies” that underlie this failure….

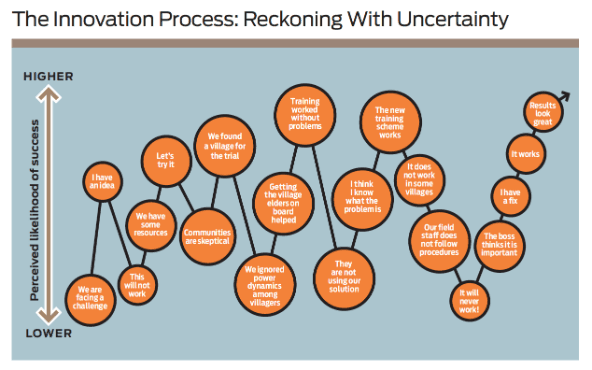

The core purpose of an innovation process is the conversion of uncertainty into knowledge. Or to put it another way: Innovation is essentially a matter of learning. In fact, one critical insight that we have drawn from our research is that effective organizations approach innovation not with an expectation of success but with an expectation of learning. Innovators who expect success from innovation efforts will inevitably encounter disappointment, and the experience of failure will generate a blame culture in their organization that dramatically lowers their chance of achieving positive impact. But a focus on learning creates a sense of progress rather than a sense of failure. The high-impact organizations that we have studied owe much of their success to their wealth of accumulated knowledge—knowledge that often has emerged from failed innovation efforts.

Innovation uncertainty has multiple dimensions, and organizations need to be vigilant about addressing uncertainty in all of its forms. (See “Types of Innovation Uncertainty” below.) Let’s take a close look at three aspects of the innovation process that often involve a considerable degree of uncertainty.

Problem formulation | Organizations may incorrectly frame the problem that they aim to solve, and identifying that problem accurately may require several iterations and learning cycles…

Solution development | Even when an organization has an adequate understanding of a problem, it may not be able to access and deploy the resources needed to create an effective and robust solution….

Alignment with identity | Innovation may lead an organization in a direction that does not fit its culture or its sense of its purpose—its sense of “who we are.”…

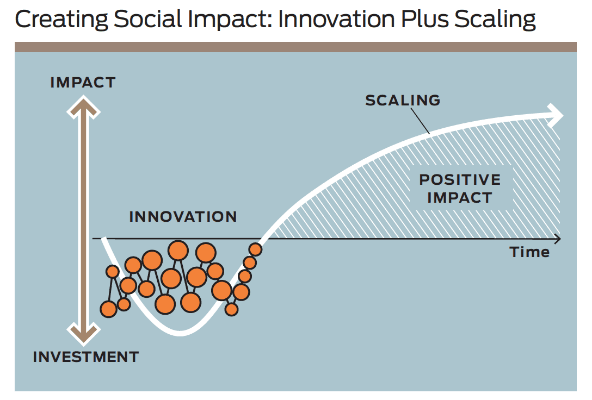

In short, innovation plus scaling equals impact. Innovation is an investment of resources that creates a new potential; scaling creates impact by enacting that potential. Because innovation creates only the potential for impact, we advocate replacing the assumption that “innovation is good, and more is better” with a more critical view: Innovation, we argue, needs to prove itself on the basis of the impact that it actually creates. The goal is not innovation for its own sake but productive innovation.

Productive innovation depends on two factors: (1) an organization’s capacity for efficiently replacing innovation uncertainty with knowledge, and (2) its ability to scale up innovation outcomes by enhancing its organizational effectiveness. Innovation and scaling thus work together to form an overall social impact creation process. Over time, an investment in innovation—in the work of overcoming uncertainty—yields positive social impact, and the value of such impact will eventually exceed the cost of that investment. But that will be the case only if an organization is able to master the scaling part of this process….

Focusing on Pathologies

Through our study of social enterprises, we have devised a set of six pathologies—six ways that organizations limit their capacity for productive innovation. From the stage when people first develop (or fail to develop) the idea for an innovation to the stage when scaling efforts take off (or fail to take off), these pathologies adversely affect an organization’s ability to make its way through the social impact creation process. (See “Creating Social Impact: Six Innovation Pathologies to Avoid” below.) Organizations can greatly improve the impact of their innovation efforts by working to prevent or treat these pathologies.

Never getting started | In too many cases, organizations simply fail to invest seriously in the work of innovation. This pathology has many causes. People in organizations may have neither the time nor the incentive to develop or communicate new ideas. Or they may find that their ideas fall on deaf ears. Or they may have a tendency to discuss an idea endlessly—until the problem that gave rise to it has been replaced by another urgent problem or until an opportunity has vanished….

Pursuing too many bad ideas | Organizations in the social sector frequently fall into the habit of embracing a wide variety of ideas for innovation without regard to whether those ideas are sound. The recent obsession with “scientific” evaluation tools such as randomized controlled trials, or RCTs, exemplifies this tendency to favor costly ideas that may or may not deliver real benefits. As with other pathologies, many factors potentially contribute to this one. Funders may push their favorite solutions regardless of how well they understand the problems that those solutions target or how well a solution fits a particular organization. Or an organization may fail to invest in learning about the context of a problem before adopting a solution. Wasting scarce resources on the pursuit of bad ideas creates frustration and cynicism within an organization. It also increases innovation uncertainty and the likelihood of failure….

Stopping too early | In some instances, organizations are unable or unwilling to devote adequate resources to the development of worthy ideas. When resources are scarce and not formally dedicated to innovation processes, project managers will struggle to develop an idea and may have to abandon it prematurely. Too often, they end up taking the blame for failure, and others in their organization ignore the adverse circumstances that caused it. Decision makers then reallocate resources on an ad-hoc basis to other urgent problems or to projects that seem more important. As a result, even promising innovation efforts come to a grinding halt….

Stopping too late | Even more costly than stopping too early is stopping too late. In this pathology, an organization continues an innovation project even after the innovation proves to be ineffective or unworkable. This problem occurs, for example, when an unsuccessful innovation happens to be the pet project of a senior leader who has limited experience. Leaders who have recently joined an organization and who are keen to leave their mark rather than continue what their predecessor has built are particularly likely to engage in this pathology. Another cause of “stopping too late” is the assumption that a project budget needs to be spent. The consequences of this pathology are clear: Organizations expend scarce resources with little hope for success and without gaining any useful knowledge….

Scaling too little | To repeat an essential point that we made earlier: no scaling, no impact. This pathology—which involves a failure to move beyond the initial stages of developing, launching, and testing an intervention—is all too common in the social enterprise field. Thousands of inspired young people want to become social entrepreneurs. But few of them are willing or able to build an organization that can deliver solutions at scale. Too many organizations, therefore, remain small and lack the resources and capabilities required for translating innovation into impact….

Innovating again too soon | Too many organizations rush to launch new innovation projects instead of investing in efforts to scale interventions that they have already developed. The causes of this pathology are fairly well known: People often portray scaling as dull, routine work and innovation as its more attractive sibling. “Innovative” proposals thus attract funders more readily than proposals that focus on scaling. Reinforcing this bias is the preference among many funders for “lean projects” that reduce overhead costs to a minimum. These factors lead organizations to jump opportunistically from one innovation grant to another….(More)”

Ed Parkes, at Gov.UK: “Back in April we set out our plan for the discovery phase for what we are now calling “data science literacy”. We explained that we were going to undertake user research with civil servants to understand how they use data. The discovery phase has helped clarify the focus of this work, and we have now begun to develop options for a data science literacy service for government.

Discovery has helped us understand what we really mean when we say ‘data literacy’. For one person it can be a basic understanding of statistics, but to someone else it might mean knowledge of new data science approaches. But on the basis of our exploration, we have started to use the term “data science literacy” to mean the ability to understand how new data science techniques and approaches can be applied in real world contexts in the civil service, and to distinguish it from a broader definition of ‘data literacy’….

In the spirit of openness and transparency we are making this long list of ideas available here:

Data science driven apps

One way in which civil servants could come to understand the opportunities of data science would be to experience products and services which are driven by data science in their everyday roles. This could be something like having a recommendation engine for actions provided to them on the basis of information already held on the customer.

Sharing knowledge across government

A key user need from our user research was to understand how others had undertaken data science projects in government. This could be supported by something like a series of videos / podcasts created by civil servants, setting out case studies and approaches to data science in government. Alternatively, we could have a regularly organised speaker series where data science projects across government are presented alongside outside speakers.

Support for using data science in departments

Users in departments need to understand and experience data science projects in government so that they can undertake their own. Potentially this could be achieved through policy, analytical and data science colleagues working in multidisciplinary teams. Colleagues could also be supported by tools of differing levels of complexity ranging from a simple infographic showing at a high level the types of data available in a department to an online tool which diagnoses which approach people should take for a data science project on the basis of their aims and the data available to them.

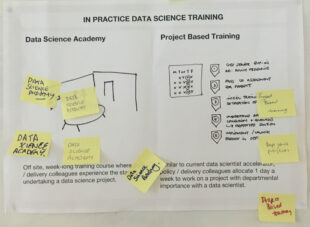

In practice training

Users could learn more about how to use data science in their jobs by attending more formal training courses. These could take the form of something like an off-site, week-long training course where they experience the stages of undertaking a data science project (similar to the DWP Digital Academy). An alternative model could be to allocate one day a week to work on a project with departmental importance with a data scientist (similar to theData Science Accelerator Programme for analysts).

Cross-government support for collaboration

For those users who have responsibility for leading on data science transformation in their departments there is also a need to collaborate with others in similar roles. This could be achieved through interventions such as a day-long unconference to discuss anything related to data science, and using online tools such as Google Groups, Slack, Yammer, Trello etc. We also tested the idea of a collaborative online resource where data science leads and others can contribute content and learning materials / approaches.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of potential ways to encourage data science thinking by policy and delivery colleagues across government. We hope this list is of interest to others in the field and we will update in the next six months about the transition of this project to Alpha….(More)”

Brian R. Calfano on “addressing social and political ills through the solutions journalism approach” in The Blue Review: “…To effectively work in the public interest as a member of the media covering politics in a national election year, I argue that stories evaluating and proposing solutions to our major societal problems must be an integral part of the media menu served to the public. Solutions are certainly not the only thing we need to cover in the media, but greater focus on problem solving is needed than what is provided at present.

A “solutions journalism” approach to covering political stories holds promise because it focuses attention on the evaluation of effectiveness in dealing with some of the most pressing problems we face as a society. Along the way, the solutions-based focus may even tamp down the incivility that plagues our politics.The author is a member of the Solutions Journalism Network.

So, how do we get started with a solutions journalism approach?

The Solutions Journalism Network has already done much of the legwork in setting up the scaffolding for journalists looking to sink their teeth into the consideration of “what works” in solving a social problem.

In their Solutions Journalism Toolkit (2015, pdf), the Solutions Journalism Network suggests focusing on the following questions when determining a topic to cover (pgs. 6-7):

- Does the story explain the causes of social problem?

- Does the story present an associated response to that problem?

- Does the story get into the problem solving and how to details of implementation?

- Does the story present evidence of results linked to the response?

- Does the story explain limitations of the response?

- Does the story convey an insight or teachable lesson?

…Most interesting about this approach is that it calls on my experience as a social science researcher. I’m tempted to go into full researcher mode and critique the all-too-frequent use of basic cross-tabulations and observational survey data as means for showing cause and effect. Generally speaking, audiences may not care about research methods, but my job is to make the story compelling enough — including the bits about methodology — to make them interested.

Importantly, I’m not alone in this effort. Sources like the website evidencebasedprograms.org feature a litany of randomized controlled trials that allow determination of direct impact from a policy intervention on issues like the “cliff effect.”

My work is made more difficult if the organizations I interview for the solutions journalism stories on the “cliff effect” are not using the randomized trial approach. At the least, I’ll have to point out to the viewer that the solutions an organization proposes are not being evaluated with the strongest possible assessment tools. This is not so much a problem, however, as an opportunity, as the organization might benefit from the critique of its own evaluation practices to find what works “better than average.”…(More)”.

Book by Mary Ellen Hannibal: “…Here is a wide-ranging adventure in becoming a citizen scientist by an award-winning writer and environmental thought leader. As Mary Ellen Hannibal wades into tide pools, follows hawks, and scours mountains to collect data on threatened species, she discovers the power of a heroic cast of volunteers—and the makings of what may be our last, best hope in slowing an unprecedented mass extinction.

Digging deeply, Hannibal traces today’s tech-enabled citizen science movement to its roots: the centuries-long tradition of amateur observation by writers and naturalists. Prompted by her novelist father’s sudden death, she also examines her own past—and discovers a family legacy of looking closely at the world. With unbending zeal for protecting the planet, she then turns her gaze to the wealth of species left to fight for.

Combining original reporting, meticulous research, and memoir in impassioned prose, Citizen Scientist is a literary event, a blueprint for action, and the story of how one woman rescued herself from an odyssey of loss—with a new kind of science….(More)”