Norman Fenton, Magda Osman, Martin Neil, and Scott McLachlan at The Conversation: “Suppose we wanted to estimate how many car owners there are in the UK and how many of those own a Ford Fiesta, but we only have data on those people who visited Ford car showrooms in the last year. If 10% of the showroom visitors owned a Fiesta, then, because of the bias in the sample, this would certainly overestimate the proportion of Ford Fiesta owners in the country.

Estimating death rates for people with COVID-19 is currently undertaken largely along the same lines. In the UK, for example, almost all testing of COVID-19 is performed on people already hospitalised with COVID-19 symptoms. At the time of writing, there are 29,474 confirmed COVID-19 cases (analogous to car owners visiting a showroom) of whom 2,352 have died (Ford Fiesta owners who visited a showroom). But it misses out all the people with mild or no symptoms.

Concluding that the death rate from COVID-19 is on average 8% (2,352 out of 29,474) ignores the many people with COVID-19 who are not hospitalised and have not died (analogous to car owners who did not visit a Ford showroom and who do not own a Ford Fiesta). It is therefore equivalent to making the mistake of concluding that 10% of all car owners own a Fiesta.

There are many prominent examples of this sort of conclusion. The Oxford COVID-19 Evidence Service have undertaken a thorough statistical analysis. They acknowledge potential selection bias, and add confidence intervals showing how big the error may be for the (potentially highly misleading) proportion of deaths among confirmed COVID-19 patients.

They note various factors that can result in wide national differences – for example the UK’s 8% (mean) “death rate” is very high compared to Germany’s 0.74%. These factors include different demographics, for example the number of elderly in a population, as well as how deaths are reported. For example, in some countries everybody who dies after having been diagnosed with COVID-19 is recorded as a COVID-19 death, even if the disease was not the actual cause, while other people may die from the virus without actually having been diagnosed with COVID-19.

However, the models fail to incorporate explicit causal explanations in their modelling that might enable us to make more meaningful inferences from the available data, including data on virus testing.

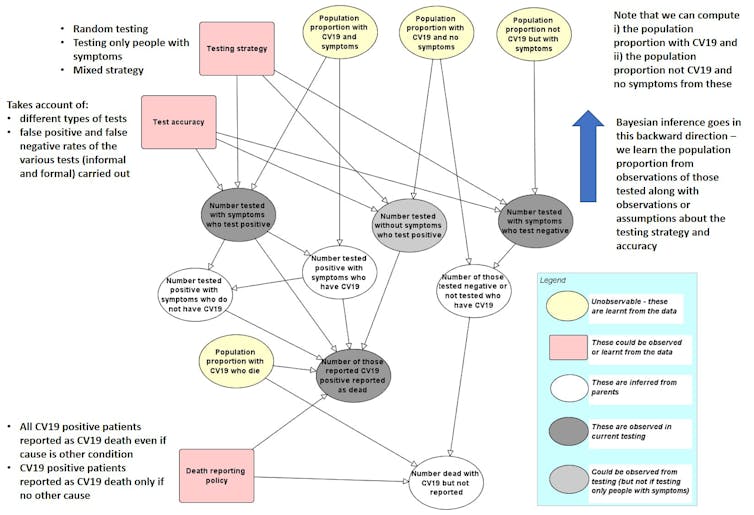

We have developed an initial prototype “causal model” whose structure is shown in the figure above. The links between the named variables in a model like this show how they are dependent on each other. These links, along with other unknown variables, are captured as probabilities. As data are entered for specific, known variables, all of the unknown variable probabilities are updated using a method called Bayesian inference. The model shows that the COVID-19 death rate is as much a function of sampling methods, testing and reporting, as it is determined by the underlying rate of infection in a vulnerable population….(More)”