Paper by Fernando Delgado, Stephen Yang, Michael Madaio, and Qian Yang: “Despite the growing consensus that stakeholders affected by AI systems should participate in their design, enormous variation and implicit disagreements exist among current approaches. For researchers and practitioners who are interested in taking a participatory approach to AI design and development, it remains challenging to assess the extent to which any participatory approach grants substantive agency to stakeholders. This article thus aims to ground what we dub the “participatory turn” in AI design by synthesizing existing theoretical literature on participation and through empirical investigation and critique of its current practices. Specifically, we derive a conceptual framework through synthesis of literature across technology design, political theory, and the social sciences that researchers and practitioners can leverage to evaluate approaches to participation in AI design. Additionally, we articulate empirical findings concerning the current state of participatory practice in AI design based on an analysis of recently published research and semi-structured interviews with 12 AI researchers and practitioners. We use these empirical findings to understand the current state of participatory practice and subsequently provide guidance to better align participatory goals and methods in a way that accounts for practical constraints…(More)”.

Public Net Worth

Book by Jacob Soll, Willem Buiter, John Crompton, Ian Ball, and Dag Detter: “As individuals, we depend on the services that governments provide. Collectively, we look to them to tackle the big problems – from long-term climate and demographic change to short-term crises like pandemics or war. This is very expensive, and is getting more so.

But governments don’t provide – or use – basic financial information that every business is required to maintain. They ignore the value of public assets and most liabilities. This leads to inefficiency and bad decision-making, and piles up problems for the future.

Governments need to create balance sheets that properly reflect assets and liabilities, and to understand their future obligations and revenue prospects. Net Worth – both today and for the future – should be the measure of financial strength and success.

Only if this information is put at the centre of government financial decision-making can the present challenges to public finances around the world be addressed effectively, and in a way that is fair to future generations.

The good news is that there are ways to deal with these problems and make government finances more resilient and fairer to future generations.

The facts, and the solutions, are non-partisan, and so is this book. Responsible leaders of any political persuasion need to understand the issues and the tools that can enable them to deliver policy within these constraints…(More)”.

Open: A Pan-ideological Panacea, a Free Floating Signifier

Paper by Andrea Liu: “Open” is a word that originated from FOSS (Free and Open Software movement) to mean a Commons-based, non-proprietary form of computer software development (Linux, Apache) based on a decentralized, poly-hierarchical, distributed labor model. But the word “open” has now acquired an unnerving over-elasticity, a word that means so many things that at times it appears meaningless. This essay is a rhetorical analysis (if not a deconstruction) of how the term “open” functions in digital culture, the promiscuity (if not gratuitousness) with which the term “open” is utilized in the wider society, and the sometimes blatantly contradictory ideologies a indiscriminately lumped together under this word…(More)”

Data Sandboxes: Managing the Open Data Spectrum

Primer by Uma Kalkar, Sampriti Saxena, and Stefaan Verhulst: “Opening up data offers opportunities to enhance governance, elevate public and private services, empower individuals, and bolster public well-being. However, achieving the delicate balance between open data access and the responsible use of sensitive and valuable information presents complex challenges. Data sandboxes are an emerging approach to balancing these needs.

In this white paper, The GovLab seeks to answer the following questions surrounding data sandboxes: What are data sandboxes? How can data sandboxes empower decision-makers to unlock the potential of open data while maintaining the necessary safeguards for data privacy and security? Can data sandboxes help decision-makers overcome barriers to data access and promote purposeful, informed data (re-)use?

After evaluating a series of case studies, we identified the following key findings:

- Data sandboxes present six unique characteristics that make them a strong tool for facilitating open data and data re-use. These six characteristics are: controlled, secure, multi-sectoral and collaborative, high computing environments, temporal in nature, adaptable, and scalable.

- Data sandboxes can be used for: pre-engagement assessment, data mesh enablement, rapid prototyping, familiarization, quality and privacy assurance, experimentation and ideation, white labeling and minimization, and maturing data insights.

- There are many benefits to implementing data sandboxes. We found ten value propositions, such as: decreasing risk in accessing more sensitive data; enhancing data capacity; and fostering greater experimentation and innovation, to name a few.

- When looking to implement a data sandbox, decision-makers should consider how they will attract and obtain high-quality, relevant data, keep the data fresh for accurate re-use, manage risks of data (re-)use, and translate and scale up sandbox solutions in real markets.

- Advances in the use of the Internet of Things and Privacy Enhancing Technologies could help improve the creation, preparation, analysis, and security of data in a data sandbox. The development of these technologies, in parallel with European legislative measures such as the Digital Markets Act, the Data Act and the Data Governance Act, can improve the way data is unlocked in a data sandbox, improving trust and encouraging data (re-)use initiatives…(More)” (FULL PRIMER)”

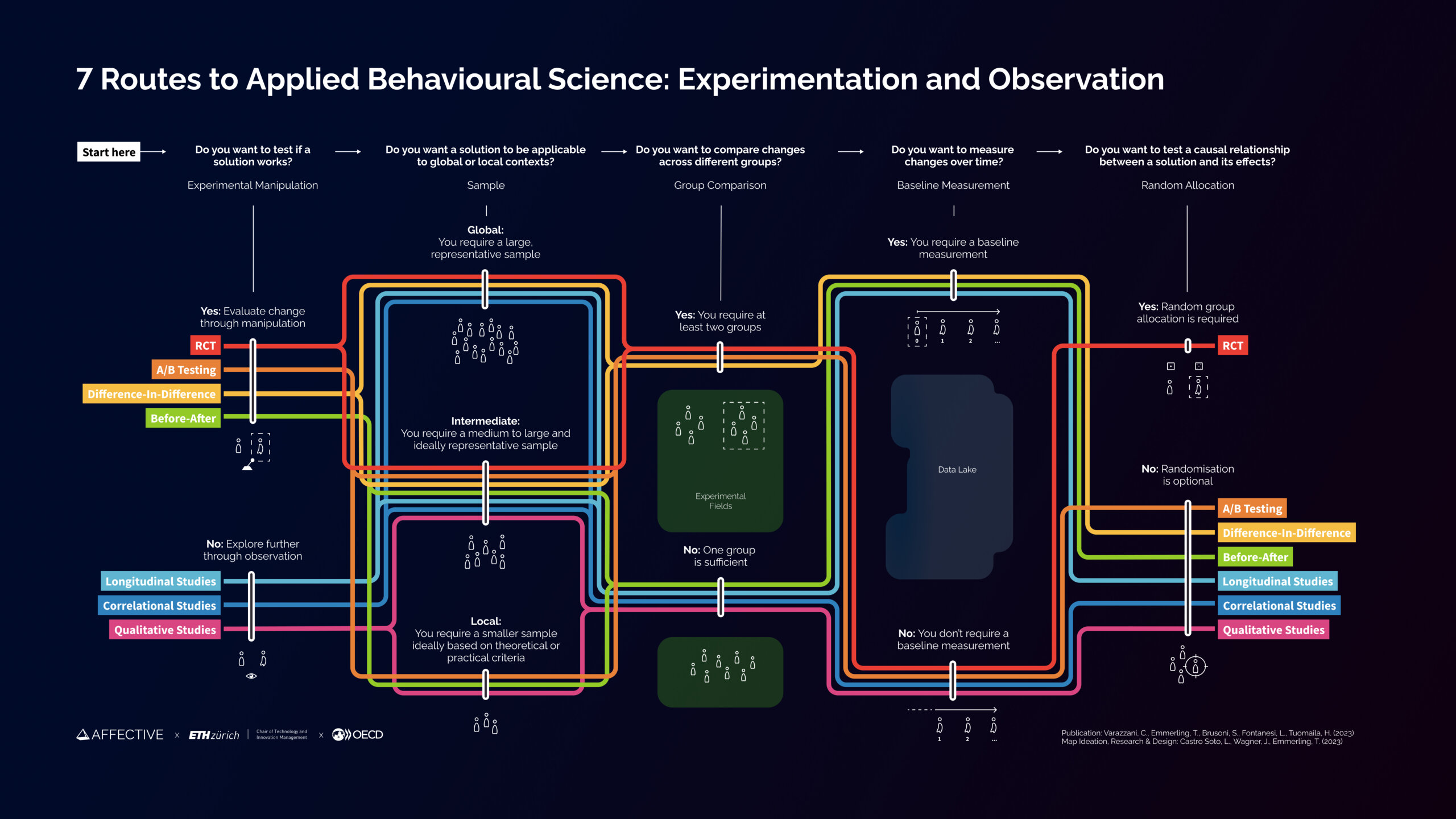

Seven routes to experimentation in policymaking: a guide to applied behavioural science methods

OECD Resource: “…offers guidelines and a visual roadmap to help policymakers choose the most fit-for-purpose evidence collection method for their specific policy challenge.

The seven applied behavioural science methods:

- Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) are experiments that can demonstrate a causal relationship between an intervention and an outcome, by randomly assigning individuals to an intervention group and a control group.

- A/B testing tests two or more manipulations (such as variants of a webpage) to assess which performs better in terms of a specific goal or metric.

- Difference-in-Difference is an experimental method that estimates the causal effect of an intervention by comparing changes in outcomes between an intervention group and a control group before and after the intervention.

- Before-After studies assess the impact of an intervention or event by comparing outcomes or measurements before and after its occurrence, without a control group.

- Longitudinal studies collect data from the same individuals or groups over an extended period to assess trends over time.

- Correlational studies help to investigate the relationship between two or more variables to determine if they vary together (without implying causation).

- Qualitative studies explore the underlying meanings and nuances of a phenomenon through interviews, focus group sessions, or other exploratory methods based on conversations and observations…(More)”.

When it comes to AI and democracy, we cannot be careful enough

Article by Marietje Schaake: “Next year is being labelled the “Year of Democracy”: a series of key elections are scheduled to take place, including in places with significant power and populations, such as the US, EU, India, Indonesia and Mexico. In many of these jurisdictions, democracy is under threat or in decline. It is certain that our volatile world will look different after 2024. The question is how — and why.

Artificial intelligence is one of the wild cards that may well play a decisive role in the upcoming elections. The technology already features in varied ways in the electoral process — yet many of these products have barely been tested before their release into society.

Generative AI, which makes synthetic texts, videos and voice messages easy to produce and difficult to distinguish from human-generated content, has been embraced by some political campaign teams. A controversial video showing a crumbling world should Joe Biden be re-elected was not created by a foreign intelligence service seeking to manipulate US elections, but by the Republican National Committee.

Foreign intelligence services are also using generative AI to boost their influence operations. My colleague at Stanford, Alex Stamos, warns that: “What once took a team of 20 to 40 people working out of [Russia or Iran] to produce 100,000 pieces can now be done by one person using open-source gen AI”.

AI also makes it easier to target messages so they reach specific audiences. This individualised experience will increase the complexity of investigating whether internet users and voters are being fed disinformation.

While much of generative AI’s impact on elections is still being studied, what is known does not reassure. We know people find it hard to distinguish between synthetic media and authentic voices, making it easy to deceive them. We also know that AI repeats and entrenches bias against minorities. Plus, we’re aware that AI companies seeking profits do not also seek to promote democratic values.

Many members of the teams hired to deal with foreign manipulation and disinformation by social media companies, particularly since 2016, have been laid off. YouTube has explicitly said it will no longer remove “content that advances false claims that widespread fraud, errors, or glitches occurred in the 2020 and other past US Presidential elections”. It is, of course, highly likely that lies about past elections will play a role in 2024 campaigns.

Similarly, after Elon Musk took over X, formerly known as Twitter, he gutted trust and safety teams. Right when defence barriers are needed the most, they are being taken down…(More)”.

International Definitions of Artificial Intelligence

Report by IAPP: “Computer scientist John McCarthy coined the term artificial intelligence in 1955, defining it as “the science and engineering of making intelligent machines.” He organized the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence a year later — an event that many consider the birthplace of the field.

In today’s world, the definition of AI has been in continuous evolution, its contours and constraints changing to align with current and perhaps future technological progress and cultural contexts. In fact, most papers and articles are quick to point out the lack of common consensus around the definition of AI. As a resource from British research organization the Ada Lovelace Institute states, “We recognise that the terminology in this area is contested. This is a fast-moving topic, and we expect that terminology will evolve quickly.” The difficulty in defining AI is illustrated by what AI historian Pamela McCorduck called the “odd paradox,” referring to the idea that, as computer scientists find new and innovative solutions, computational techniques once considered AI lose the title as they become common and repetitive.

The indeterminate nature of the term poses particular challenges in the regulatory space. Indeed, in 2017 a New York City Council task force downgraded its mission to regulate the city’s use of automated decision-making systems to just defining the types of systems subject to regulation because it could not agree on a workable, legal definition of AI.

With this understanding, the following chart provides a snapshot of some of the definitions of AI from various global and sectoral (government, civil society and industry) perspectives. The chart is not an exhaustive list. It allows for cross-contextual comparisons from key players in the AI ecosystem…(More)”

AI and Big Data: Disruptive Regulation

Book by Mark Findlay, Josephine Seah, and Willow Wong: “This provocative and timely book identifies and disrupts the conventional regulation and governance discourses concerning AI and big data. It suggests that, instead of being used as tools for exclusionist commercial markets, AI and big data can be employed in governing digital transformation for social good.

Analysing the ways in which global technology companies have colonised data access, the book reveals how trust, ethics, and digital self-determination can be reconsidered and engaged to promote the interests of marginalised stakeholders in data arrangement. Chapters examine the regulation of labour engagement in digital economies, the landscape of AI ethics, and a multitude of questions regarding participation, costs, and sustainability. Presenting several informative case studies, the book challenges some of the accepted qualifiers of frontier tech and data use and proposes innovative ways of actioning the more conventional regulatory components of big data.

Scholars and students in information and media law, regulation and governance, and law and politics will find this book to be critical reading. It will also be of interest to policymakers and the AI and data science community…(More)”.

We, the Data

Book by Wendy H. Wong: “Our data-intensive world is here to stay, but does that come at the cost of our humanity in terms of autonomy, community, dignity, and equality? In We, the Data, Wendy H. Wong argues that we cannot allow that to happen. Exploring the pervasiveness of data collection and tracking, Wong reminds us that we are all stakeholders in this digital world, who are currently being left out of the most pressing conversations around technology, ethics, and policy. This book clarifies the nature of datafication and calls for an extension of human rights to recognize how data complicate what it means to safeguard and encourage human potential.

As we go about our lives, we are co-creating data through what we do. We must embrace that these data are a part of who we are, Wong explains, even as current policies do not yet reflect the extent to which human experiences have changed. This means we are more than mere “subjects” or “sources” of data “by-products” that can be harvested and used by technology companies and governments. By exploring data rights, facial recognition technology, our posthumous rights, and our need for a right to data literacy, Wong has crafted a compelling case for engaging as stakeholders to hold data collectors accountable. Just as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights laid the global groundwork for human rights, We, the Data gives us a foundation upon which we claim human rights in the age of data…(More)”.

Extremely Online: The Untold Story of Fame, Influence, and Power on the Internet

Book by Taylor Lorenz: “For over a decade, Taylor Lorenz has been the authority on internet culture, documenting its far-reaching effects on all corners of our lives. Her reporting is serious yet entertaining and illuminates deep truths about ourselves and the lives we create online. In her debut book, Extremely Online, she reveals how online influence came to upend the world, demolishing traditional barriers and creating whole new sectors of the economy. Lorenz shows this phenomenon to be one of the most disruptive changes in modern capitalism.

By tracing how the internet has changed what we want and how we go about getting it, Lorenz unearths how social platforms’ power users radically altered our expectations of content, connection, purchasing, and power. Lorenz documents how moms who started blogging were among the first to monetize their personal brands online, how bored teens who began posting selfie videos reinvented fame as we know it, and how young creators on TikTok are leveraging opportunities to opt out of the traditional career pipeline. It’s the real social history of the internet.

Emerging seemingly out of nowhere, these shifts in how we use the internet seem easy to dismiss as fads. However, these social and economic transformations have resulted in a digital dynamic so unappreciated and insurgent that it ultimately created new approaches to work, entertainment, fame, and ambition in the 21st century…(More)”.