Article by Margaret Talbot: “If you have spent time on Wikipedia—and especially if you’ve delved at all into the online encyclopedia’s inner workings—you will know that it is, in almost every aspect, the inverse of Trumpism. That’s not a statement about its politics. The thousands of volunteer editors who write, edit, and fact-check the site manage to adhere remarkably well, over all, to one of its core values: the neutral point of view. Like many of Wikipedia’s s principles and procedures, the neutral point of view is the subject of a practical but sophisticated epistemological essay posted on Wikipedia. Among other things, the essay explains, N.P.O.V. means not stating opinions as facts, and also, just as important, not stating facts as opinions. (So, for example, the third sentence of the entry titled “Climate change” states, with no equivocation, that “the current rise in global temperatures is driven by human activities, especially fossil fuel burning since the Industrial Revolution.”)…So maybe it should come as no surprise that Elon Musk has lately taken time from his busy schedule of dismantling the federal government, along with many of its sources of reliable information, to attack Wikipedia. On January 21st, after the site updated its page on Musk to include a reference to the much-debated stiff-armed salute he made at a Trump inaugural event, he posted on X that “since legacy media propaganda is considered a ‘valid’ source by Wikipedia, it naturally simply becomes an extension of legacy media propaganda!” He urged people not to donate to the site: “Defund Wikipedia until balance is restored!” It’s worth taking a look at how the incident is described on Musk’s page, quite far down, and judging for yourself. What I see is a paragraph that first describes the physical gesture (“Musk thumped his right hand over his heart, fingers spread wide, and then extended his right arm out, emphatically, at an upward angle, palm down and fingers together”), goes on to say that “some” viewed it as a Nazi or a Roman salute, then quotes Musk disparaging those claims as “politicized,” while noting that he did not explicitly deny them. (There is also now a separate Wikipedia article, “Elon Musk salute controversy,” that goes into detail about the full range of reactions.)

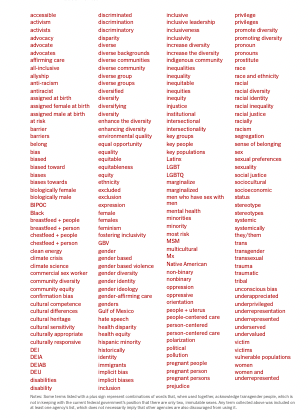

This is not the first time Musk has gone after the site. In December, he posted on X, “Stop donating to Wokepedia.” And that wasn’t even his first bad Wikipedia pun. “I will give them a billion dollars if they change their name to Dickipedia,” he wrote, in an October, 2023, post. It seemed to be an ego thing at first. Musk objected to being described on his page as an “early investor” in Tesla, rather than as a founder, which is how he prefers to be identified, and seemed frustrated that he couldn’t just buy the site. But lately Musk’s beef has merged with a general conviction on the right that Wikipedia—which, like all encyclopedias, is a tertiary source that relies on original reporting and research done by other media and scholars—is biased against conservatives.

The Heritage Foundation, the think tank behind the Project 2025 policy blueprint, has plans to unmask Wikipedia editors who maintain their privacy using pseudonyms (these usernames are displayed in the article history but don’t necessarily make it easy to identify the people behind them) and whose contributions on Israel it deems antisemitic…(More)”.