Essay by Stefaan G. Verhulst, Lisa T. Moretti, Hannah Chafetz and Alex Fischer: “…How can philanthropies move in a more deliberate yet responsible manner toward using data to advance their goals? The purpose of this article is to propose an overview of existing and potential qualitative and quantitative data innovations within the philanthropic sector. In what follows, we examine four areas where there is a need for innovation in how philanthropy works, and eight pathways for the responsible use of data innovations to address existing shortcomings.

Four areas for innovation

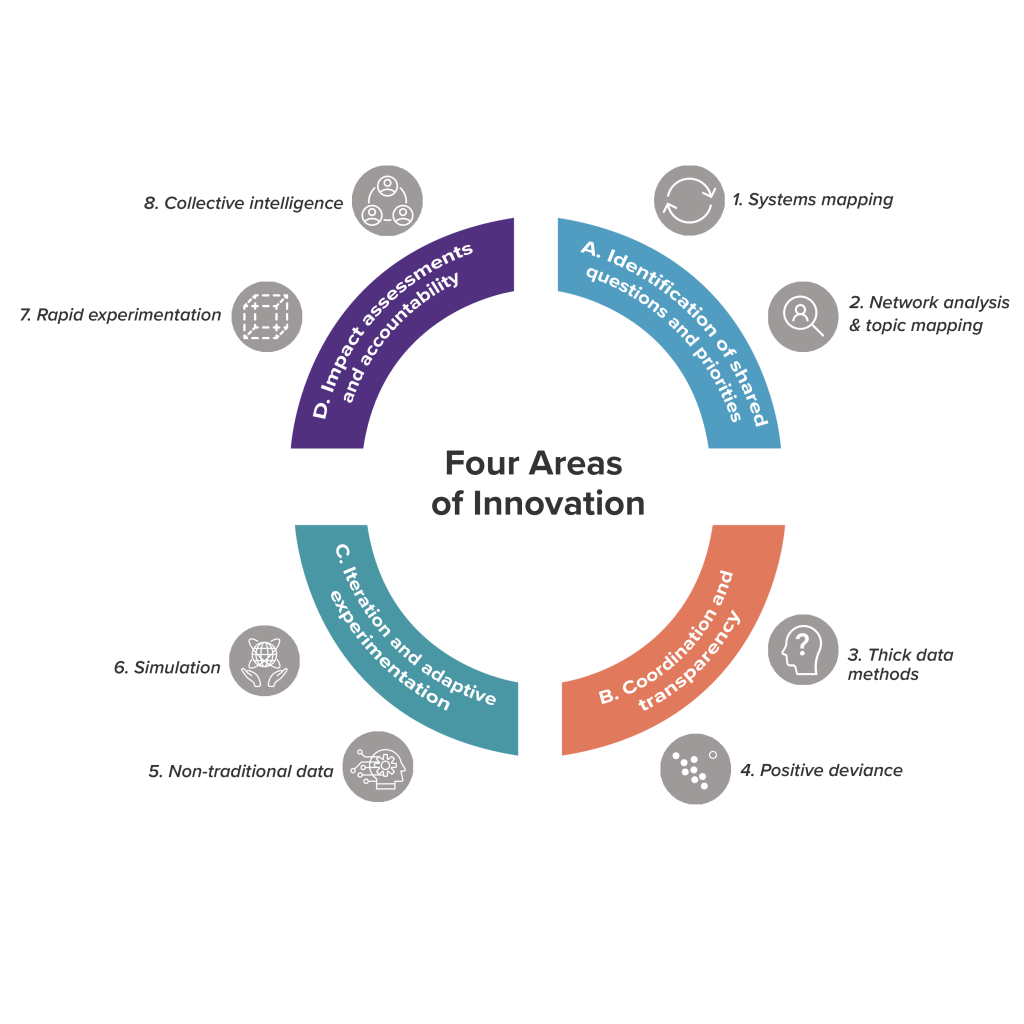

In order to identify potential data-led solutions, we need to begin by understanding current shortcomings. Through our research, we identified four areas within philanthropy that are ripe for data-led innovation:

- First, there is a need for innovation in the identification of shared questions and overlapping priorities among communities, public service, and philanthropy. The philanthropic sector is well placed to enable a new combination of approaches, products, and processes while still enabling communities to prioritize the issues that matter most.

- Second, there is a need to improve coordination and transparency across the sector. Even when shared priorities are identified, there often remains a large gap between the imperatives of building common agendas and the ability to act on those agendas in a coordinated and strategic way. New ways to collect and generate cross-sector shared intelligence are needed to better design funding strategies and make difficult trade-off choices.

- Third, reliance on fixed-project-based funding often means that philanthropists must wait for impact reports to assess results. There is a need to enable iteration and adaptive experimentation to help foster a culture of greater flexibility, agility, learning, and continuous improvement.

- Lastly, innovations for impact assessments and accountability could help philanthropies better understand how their funding and support have impacted the populations they intend to serve.

Needless to say, data alone cannot address all of these shortcomings. For true innovation, qualitative and quantitative data must be combined with a much wider range of human, institutional, and cultural change. Nonetheless, our research indicates that when used responsibly, data-driven methods and tools do offer pathways for success. We examine some of those pathways in the next section.

Eight pathways for data-driven innovations in philanthropy

The sources of data today available to philanthropic organizations are multifarious, enabled by advancements in digital technologies such as low-cost sensors, mobile devices, apps, wearables, and the increasing number of objects connected to the Internet of Things. The ways in which this data can be deployed are similarly varied. In the below, we examine eight pathways in particular for data-led innovation…(More)”.