The paper further explains how data trusts might be used as in the governance of AI, and investigates the barriers which Singapore’s data protection law presents to the use of data trusts and how those barriers might be overcome. Its conclusion is that a mixed contractual/corporate model, with an element of regulatory oversight and audit to ensure consumer confidence that data is being used appropriately, could produce a useful AI governance tool…(More)”.

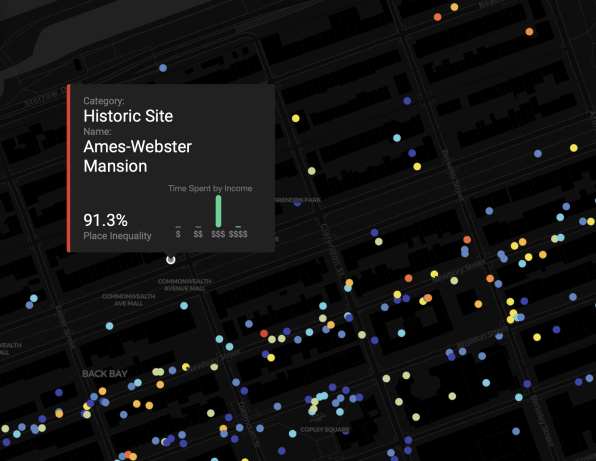

Visualizing where rich and poor people really cross paths—or don’t

Ben Paynter at Fast Company: “…It’s an idea that’s hard to visualize unless you can see it on a map. So MIT Media Lab collaborated with the location intelligence firm Cuebiqto build one. The result is called the Atlas of Inequality and harvests the anonymized location data from 150,000 people who opted

The result is an interactive view of just how filtered, sheltered, or sequestered many people’s lives really are. That’s an important thing to be reminded of at a time when the U.S. feels increasingly ideologically and economically divided. “Economic inequality isn’t just limited to neighborhoods, it’s part of the places you visit every day,” the researchers say in a mission statement about the Atlas….(More)”.

Deep Medicine: How Artificial Intelligence Can Make Healthcare Human Again

Book by Eric Topol: “Medicine has become inhuman, to disastrous effect. The doctor-patient relationship–the heart of medicine–is broken: doctors are too distracted and overwhelmed to truly connect with their patients, and medical errors and misdiagnoses abound. In Deep Medicine, leading physician Eric Topol reveals how artificial intelligence can help. AI has the potential to transform everything doctors do, from notetaking and medical scans to diagnosis and treatment, greatly cutting down the cost of medicine and reducing human mortality. By freeing physicians from the tasks that interfere with human connection, AI will create space for the real healing that takes place between a doctor who can listen and a patient who needs to be heard. Innovative, provocative, and hopeful, Deep Medicine shows us how the awesome power of AI can make medicine better, for all the humans involved….(More)”.

Machine Ethics: The Design and Governance of Ethical AI and Autonomous Systems

Introduction by A.F. Winfield, K. Michael, J. Pitt, V. Evers of Special Issue of Proceedings of the IEEE: “…The primary focus of this special issue is machine ethics, that is the question of how autonomous systems can be imbued with ethical values. Ethical autonomous systems are needed because, inevitably, near future systems are moral agents; consider driverless cars, or medical diagnosis AIs, both of which will need to make choices with ethical consequences. This special issue includes papers that describe both implicit ethical agents, that is machines designed to avoid unethical outcomes, and explicit ethical agents: machines which either encode or learn ethics and determine actions based on those ethics. Of

Some notes on smart cities and the corporatization of urban governance

Presentation by Constance Carr and Markus Hesse: “We want to address a discrepancy; that is, the discrepancy between processes and practices of technological development on one hand and/or production processes of urban change and urban problems on the other. There’s a gap here, that we can illustrate with the case of the

The scholarly literature on digital cities is quite clear that there are externalities, uncertainties

Obviously, digitization and technology have revolutionized geography in many ways. And, this is nothing new. Roughly twenty years ago, with the rise of the Internet, some, such as MIT’s Bill Mitchell (1995), speculated that it and other ITs would eradicate space into the ‘City of Bits’. However, even back then statements like these didn’t go uncriticised by those who pointed at the inherent technological determinism and exposed that there is a complex relationship between urban development, urban planning, and technological innovation; that the relationship was neither new, nor trivial such that tech, itself, would automatically and necessarily be productive, beneficial, and central to cities.

What has changed is the proliferation of digital technologies and their applications. We agree with Ash et al. (2016) that geography has experienced a ‘digital turn’ where urban geography now produced by, through and of digitization. And, while digitalization of urbanity has provided benefits, it has also come sidelong a number of unsolved problems.

First, behind the production of big data, algorithms, and digital design, there are certain epistemologies – ways of knowing. Data is not value-free. Rather, data is an end product of political and associated methods of framing that structure the production of data. So, now that we “live in a present characterized by a […] diverse array of spatially-enabled digital devices, platforms, applications and services,” (Ash et al. 2016: 28), we can interrogate how these processes and algorithms are informed by socio-economic inequalities, because the risk is that new technologies will simply reproduce them.

Second, the circulation of data around the globe invokes questions about who owns and regulates them when stored and processed in remote geographic locations

The Governance of Digital Technology, Big Data, and the Internet: New Roles and Responsibilities for Business

Introduction to Special Issue of Business and Society by Dirk Matten, Ronald Deibert & Mikkel Flyverbom: “The importance of digital technologies for social and economic developments and a growing focus on data collection and privacy concerns have made the Internet a salient and visible issue in global politics. Recent developments have increased the awareness that the current approach of governments and business to the governance of the Internet and the adjacent technological spaces raises a host of ethical issues. The significance and challenges of the digital age have been further accentuated by a string of highly exposed cases of surveillance and a growing concern about issues of privacy and the power of this new industry. This special issue explores what some have referred to as the “Internet-industrial complex”—the intersections between business, states, and other actors in the shaping, development, and governance of the Internet…(More)”.

The Palgrave Handbook of Global Health Data Methods for Policy and Practice

Book edited by Sarah B. Macfarlane and Carla AbouZahr: “This handbook compiles methods for gathering, organizing and disseminating data to inform policy and manage health systems worldwide. Contributing authors describe national and international structures for generating data and explain the relevance of ethics, policy, epidemiology, health economics, demography, statistics, geography and qualitative methods to describing population health. The reader, whether a student of global health, public health practitioner, programme manager, data analyst or policymaker, will appreciate the methods, context

Regulating disinformation with artificial intelligence

Paper for the European Parliamentary Research Service: “This study examines the consequences of the increasingly prevalent use of artificial intelligence (AI) disinformation initiatives upon freedom of expression, pluralism and the functioning of a democratic polity. The study examines the trade-offs in using automated technology to limit the spread of disinformation online. It presents options (from self-regulatory to legislative) to regulate automated content recognition (ACR) technologies in this context. Special attention is paid to the opportunities for the European Union as a whole to take the lead in setting the framework for designing these technologies in a way that enhances accountability and transparency and respects free speech. The present project reviews some of the key academic and policy ideas on technology and disinformation and highlights their relevance to European policy.

Chapter 1 introduces the background to the study and presents the definitions used. Chapter 2 scopes the policy boundaries of disinformation from economic, societal and technological perspectives, focusing on the media context,

Toward an Open Data Bias Assessment Tool Measuring Bias in Open Spatial Data

Working Paper by Ajjit Narayanan and Graham MacDonald: “Data is a critical resource for government decisionmaking, and in recent years, local governments, in a bid for transparency, community engagement, and innovation, have released many municipal datasets on publicly accessible open data portals. In recent years, advocates, reporters, and others have voiced concerns about the bias of algorithms used to guide public decisions and the data that power them.

Although significant progress is being made in developing tools for algorithmic bias and transparency, we could not find any standardized tools available for assessing bias in open data itself. In other words, how can policymakers, analysts, and advocates systematically measure the level of bias in the data that power city decisionmaking, whether an algorithm is used or not?

To fill this gap, we present a prototype of an automated bias assessment tool for geographic data. This new tool will allow city officials, concerned residents, and other stakeholders to quickly assess the bias and representativeness of their data. The tool allows users to upload a file with latitude and longitude coordinates and receive simple metrics of spatial and demographic bias across their city.

The tool is built on geographic and demographic data from the Census and assumes that the population distribution in a city represents the “ground truth” of the underlying distribution in the data uploaded. To provide an illustrative example of the tool’s use and output, we test our bias assessment on three datasets—bikeshare station locations, 311 service request locations, and Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) building locations—across a few, hand-selected example cities….(More)”

Circular City Data

First Volume of Circular City, A Research Journal by New Lab edited by André Corrêa d’Almeida: “…Circular City Data is the topic being explored in the first iteration of New Lab’s The Circular City program, which looks at data and knowledge as the energy, flow, and medium of collaboration. Circular data refers to the collection, production, and exchange of data, and business insights, between a series of collaborators around a shared set of inquiries. In some scenarios, data may be produced by start-ups and of high value to the city; in other cases, data may be produced by the city and of potential value to the public, start-ups, or enterprise companies. The conditions that need to be in place to safely, ethically, and efficiently extrapolate the highest potential value from data are what this program aims to uncover.

Similar to living systems, urban systems can be enhanced if the total pool of data available, i.e., energy, can be democratized and decentralized and data analytics used widely to positively impact quality of life. The abundance of data available, the vast differences in capacity across organizations to handle it, and the growing complexity of urban challenges provides an opportunity to test how principles of circular city data can help establish new forms of public and private partnerships that make cities more economically prosperous, livable, and resilient. Though we talk of an overabundance of data, it is often still not visible or tactically wielded at the local level in a way that benefits people.

Circular City Data is an effort to build a safe environment whereby start-ups, city agencies, and larger firms can collect, produce, access and exchange data, as well as business insights, through transaction mechanisms that do not necessarily require currency, i.e., through reciprocity. Circular data is data that travels across a number of stakeholders, helping to deliver insights and make clearer the opportunities where such stakeholders can work together to improve outcomes. It includes cases where a set of “circular” relationships need to be in place in order to produce such data and business insights. For example, if an AI company lacks access to raw data from the city, they won’t be able to provide valuable insights to the city. Or, Numina required an established relationship with the DBP in order to access infrastructure necessary for them to install their product and begin generating data that could be shared back with them. ***

Next, the case study documents and explains how The Circular City program was conceived, designed, and implemented, with the goal of offering lessons for scalability at New Lab and replicability in other cities around the world. The three papers that follow investigate and methodologically test the value of circular data applied to three different, but related, urban challenges: economic growth, mobility, and resilience.

Contents

- Introduction to The Circular City Research Program (André Corrêa d’Almeida)

- The Circular City Program: The Case Study (André Corrêa d’Almeida and Caroline McHeffey)

- Circular Data for a Circular City: Value Propositions for Economic Development (Stefaan G. Verhulst, Andrew Young, and Andrew J. Zahuranec)

- Circular Data for a Circular City: Value Propositions for Mobility (Arnaud Sahuguet)

- Circular Data for a Circular City: Value Propositions for Resilience and Sustainability (Nilda Mesa)

Conclusio (André Corrêa d’Almeida)