ILO Working paper 87: “Human-centered social security administrations keep the human dimension in control of decision-making. This is made possible through the insight to be gained from digital data-driven innovation in policy and governance and managerial reforms. Moreover, there are risks associated with collecting and analysing people’s digital data analysed and using it to further automate business processes. Human centricity is examined in this paper, through a human + machine approach, starting with social policy through to service delivery. Machines using AI and related technologies are designed to aug¬ment rather than replace human decision-making capability. This augmentation approach is essential in matters where discretion, compassion, reasoning, judgement, and empathy are essential for equity, fair¬ness, and fiscal responsibility within social security administration. This working paper presents a series of vignette style case studies (13) as examples of digitisation and/or digitalisation in the context of human centricity in social security administration…(More)”.

Design-led policy and governance in practice: a global perspective

Paper by Marzia Mortati, Louise Mullagh & Scott Schmidt: “Presently, the relationship between policy and design is very much open for debate as to how these two concepts differ, relate, and interact with one another. There exists very little agreement on their relational trajectory with one course, policy design, originating in the policy studies tradition while the other, design for policy, being founded in design studies. The Special Issue has paid particular attention to the upcoming area of research where design disciplines and policy studies are exploring new ways toward convergence. With a focus on design, the authors herein present an array of design methods and approaches through case studies and conceptual papers, using co-design, participatory design and critical service design to work with policymakers in tackling challenging issues and policies. We see designers and policymakers working with communities to boost engagement around the world, with examples from the UK, Latvia, New Zealand, Denmark, Turkey, the UK, Brazil and South Africa. Finally, we offer a few reflections to build further this research area pointing out topics for further research with the hope that these will be relevant for researchers approaching the field or deepening their investigation and for bridging the academic/practice divide between design studies and policy design…(More)”.

Closing the gap between user experience and policy design

Article by Cecilia Muñoz & Nikki Zeichner: “..Ask the average American to use a government system, whether it’s for a simple task like replacing a Social Security Card or a complicated process like filing taxes, and you’re likely to be met with groans of dismay. We all know that government processes are cumbersome and frustrating; we have grown used to the government struggling to deliver even basic services.

Unacceptable as the situation is, fixing government processes is a difficult task. Behind every exhausting government application form or eligibility screener lurks a complex policy that ultimately leads to what Atlantic staff writer Anne Lowrey calls the time tax, “a levy of paperwork, aggravation, and mental effort imposed on citizens in exchange for benefits that putatively exist to help them.”

Policies are complex, in part because they each represent many voices. The people who we call policymakers are key actors in governments and elected officials at every level from city councils to the U.S. Congress. As they seek to solve public problems like child poverty or improving economic mobility, they consult with experts at government agencies, researchers in academia, and advocates working directly with affected communities. They also hear from lobbyists from affected industries. They consider current events and public sentiments. All of these voices and variables, representing different and sometimes conflicting interests, contribute to the policies that become law. And as a result, laws reflect a complex mix of objectives. After a new law is in place, relevant government agencies are responsible for implementing them by creating new programs and services to carry them out. Complex policies then get translated into complex processes and experiences for members of the public. They become long application forms, unclear directions, and too often, barriers that keep people from accessing a benefit.

Policymakers and advocates typically declare victory when a new policy is signed into law; if they think about the implementation details at all, that work mostly happens after the ink is dry. While these policy actors may have deep expertise in a given issue area, or deep understanding of affected communities, they often lack experience designing services in a way that will be easy for the public to navigate…(More)”.

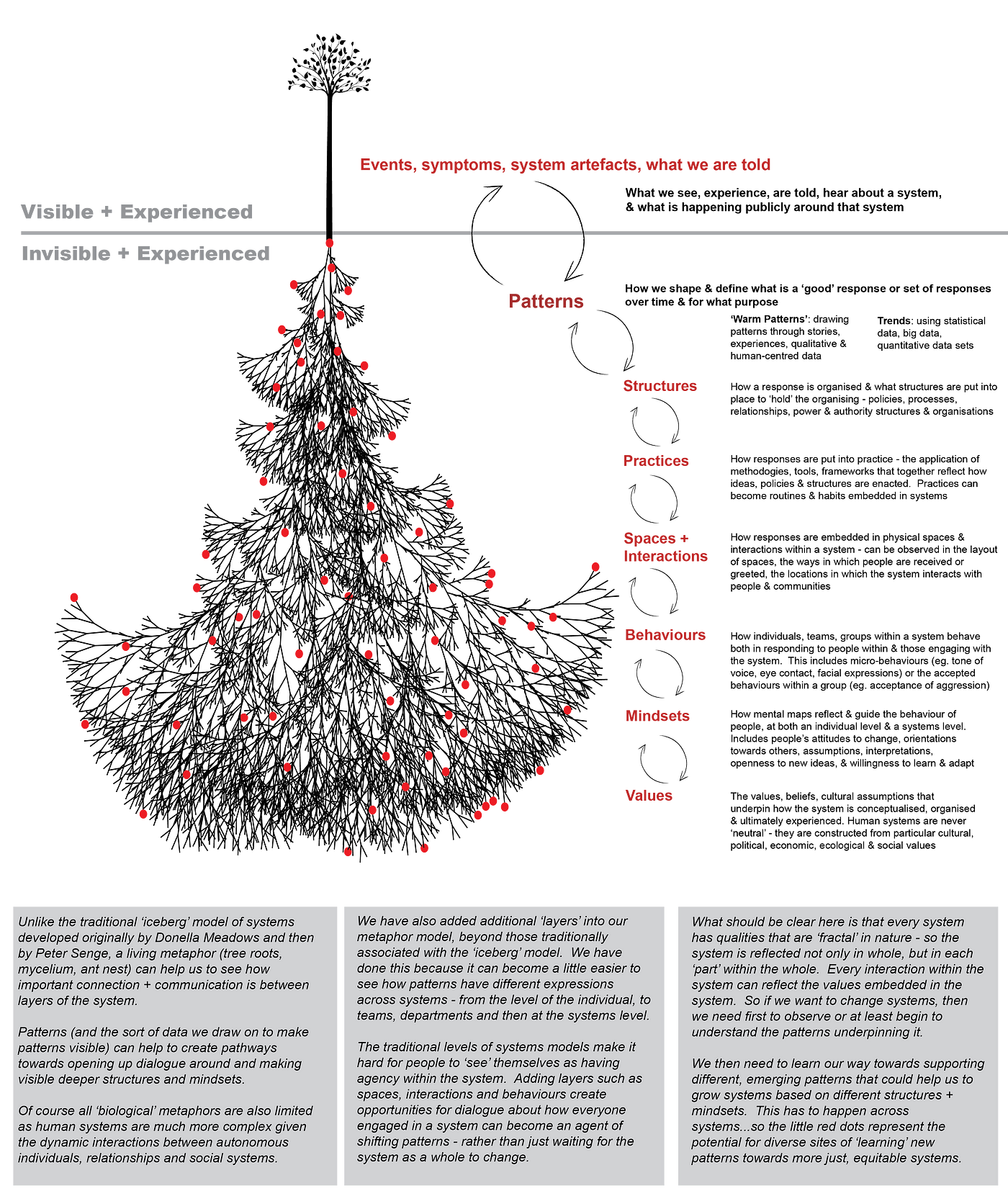

The role and power of re-patterning in systems change

Blog by Griffith University Yunus Centre: “In simple terms, patterns are interconnected behaviours, relationships and structures that together make up a picture of what ‘common practice’ looks like and how it is ultimately experienced by people interacting with and in a system.

If we take Public Services in the twenty-first century here are some examples.

Public Service organisations have most often been formed around concepts such as universal access, service delivery, social safety nets, and public provision of critical infrastructure. Built into these elements are patterns, like:

Patterns of relationships: based on objectivity, universalism, professional relationships.

Patterns of resourcing: focused on rationing, efficiency, programmatic resource flows.

Patterns of power: centred on professional expertise, needs assessments, deserving access to spaces and services.

On the surface, these are not necessarily negative and there have doubtless been many successes enabling broad access to services and infrastructure.

It’s also true though that there remain many who have not benefited, who have missed out on access or opportunity, and who have actually been harmed by and within the system.

What is needed is a foundation for public systems that moves away from goals of access to more and better servicing of communities, and towards goals around learning how we can promote patterns of thriving, aspiration, success and ‘wellbeing’…(More)”.

Inclusive Imaginaries: Catalysing Forward-looking Policy Making through Civic Imagination

UNDP Report: “Today’s complex challenges- including climate change, global health, and international security, among others – are pushing development actors to re-think and re-imagine traditional ways of working and decision-making. Transforming traditional approaches to navigating complexity would support what development thinker Sam Pitroda’s calls a ‘third vision’ demands a mindset rooted in creativity, innovation, and courage in order to one transcend national interests and takes into account global issues.

Inclusive Imaginaries is an approach that utilises collective reflection and imagination to engage with citizens, towards building more just, equitable and inclusive futures. It seeks to infuse imagination as a key process to support gathering of community perspectives rooted in lived experience and local culture, towards developing more contextual visions for policy and programme development…(More)”.

Design in the Civic Space: Generating Impact in City Government

Paper by Stephanie Wade and Jon Freach:” When design in the private sector is used as a catalyst for innovation it can produce insight into human experience, awareness of equitable and inequitable conditions, and clarity about needs and wants. But when we think of applying design in a government complex, the complicated nature of the civic arena means that public sector servants need to learn and apply design in ways that are specific to the complex ecosystem of long-standing social challenges they face, and learn new mindsets, methods, and ways of working that challenge established practices in a bureaucratic environment.

Design offers tools to help navigate the ambiguous boundaries of these complex problems and improve the city’s organizational culture so that it delivers better services to residents and the communities they live in. For the new practitioner in government, design can seem exciting, inspiring, hopeful, and fun because, over the past decade, it has quickly become a popular and novel way to approach city policy and service design. In the early part of the learning process, people often report that using design helps visualize their thoughts, spark meaningful dialogue, and find connections between problems, data, and ideas. But for some, when the going gets tough, when the ambiguity of overlapping and long-standing complex civic problems, a large number of stakeholders, causes, and effects begin to surface, design practices can seem ineffective, illogical, slow, confusing, and burdensome.

This paper will explore the highs and lows of using design in local government to help cities innovate. The authors, who have worked together to conceive, create, and deliver innovation training to over 100 global cities through multiple innovation programs, in the United States Federal Government, and in higher education, share examples from their fieldwork supported by the experiences of city staff members who have applied design methods in their jobs. Readers will discover how design works to catalyze innovative thinking in the public sector, reframe complex problems, center opportunities in resident needs, especially among those residents who have historically been excluded from government decision-making, make sensemaking a cultural norm and idea generation a ritual in otherwise traditional bureaucratic cultures, and work through the ambiguity of contemporary civic problems to generate measurable impact for residents. They will also learn why design sometimes fails to deliver its promise of innovation in government and see what happens when its language, mindsets, and tools make it hard for city innovation teams to adopt and apply…(More)”.

The Infinite Playground: A Player’s Guide to Imagination

Book by Bernard De Koven: “Bernard De Koven (1941–2018) was a pioneering designer of games and theorist of fun. He studied games long before the field of game studies existed. For De Koven, games could not be reduced to artifacts and rules; they were about a sense of transcendent fun. This book, his last, is about the imagination: the imagination as a playground, a possibility space, and a gateway to wonder. The Infinite Playground extends a play-centered invitation to experience the power and delight unlocked by imagination. It offers a curriculum for playful learning.

De Koven guides the readers through a series of observations and techniques, interspersed with games. He begins with the fundamentals of play, and proceeds through the private imagination, the shared imagination, and imagining the world—observing, “the things we imagine can become the world.” Along the way, he reminisces about playing ping-pong with basketball great Bill Russell; begins the instructions for a game called Reception Line with “Mill around”; and introduces blathering games—Blather, Group Blather, Singing Blather, and The Blather Chorale—that allow the player’s consciousness to meander freely.

Delivered during the last months of his life, The Infinite Playground has been painstakingly cowritten with Holly Gramazio, who worked together with coeditors Celia Pearce and Eric Zimmerman to complete the project as Bernie De Koven’s illness made it impossible for him to continue writing. Other prominent game scholars and designers influenced by De Koven, including Katie Salen Tekinbaş, Jesper Juul, Frank Lantz, and members of Bernie’s own family, contribute short interstitial essays…(More)”

A New Model for Saving Lives on Roads Around the World

Article by Krishen Mehta & Piyush Tewari: “…In 2016, SaveLIFE Foundation (SLF), an Indian non-profit organization, introduced the Zero Fatality Corridor (ZFC) solution, which has, since its inception, delivered an unprecedented reduction in road crash fatalities on the stretches of road where it has been deployed. The ZFC solution has adapted and added to the Safe System Approach, traditionally a western concept, to make it suitable for Indian conditions and requirements.

The Safe System Approach recognizes that people are fallible and can make mistakes that may be fatal for them or their fellow road-users—irrespective of how well they are trained.

The ZFC model, in turn, is an innovation designed specifically to accommodate the realities, resources, and existing infrastructure in low- and middle-income countries, which are vastly different from their developed counterparts. For example, unlike developed nations, people in low- and middle-income countries often live closer to the highways, and use them on a daily basis on foot or through traditional and slower modes of transportation. This gives rise to high crash conflict areas.

Some of the practices that are a part of the ZFC solution include optimized placement of ambulances at high-fatality locations, the utilization of drones to identify parked vehicles to preemptively prevent rear-end collisions, and road engineering solutions unique to the realities of countries like India. The ZFC model has helped create a secure environment specific to such countries with safer roads, safer vehicles, safer speeds, safer drivers, and rapid post-crash response.

The ZFC model was first deployed in 2016 on the Mumbai-Pune Expressway (MPEW) in Maharashtra, through a collaboration between SLF, Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation (MSRDC), and automaker Mahindra & Mahindra. From 2010 to 2016, the 95-kilometer stretch witnessed 2,579 crashes and 887 fatalities, making it one of India’s deadliest roads…(More)”.

The Power of Narrative

Essay by Klaus Schwab and Thierry Mallerett: “…The expression “failure of imagination” captures this by describing the expectation that future opportunities and risks will resemble those of the past. Novelist Graham Greene used it in The Power and the Glory, but the 9/11 Commission made it popular by invoking it as the main reason why intelligence agencies had failed to anticipate the “unimaginable” events of that day.

Ever since, the expression has been associated with situations in which strategic thinking and risk management are stuck in unimaginative and reactive thinking. Considering today’s wide and interdependent array of risks, we can’t afford to be unimaginative, even though, as the astrobiologist Caleb Scharf points out, we risk getting imprisoned in a dangerous cognitive lockdown because of the magnitude of the task. “Indeed, we humans do seem to struggle in general when too many new things are thrown at us at once. Especially when those things are outside of our normal purview. Like, well, weird viruses or new climate patterns,” Scharf writes. “In the face of such things, we can simply go into a state of cognitive lockdown, flipping from one small piece of the problem to another and not quite building a cohesive whole.”

Imagination is precisely what is required to escape a state of “cognitive lockdown” and to build a “cohesive whole.” It gives us the capacity to dream up innovative solutions to successfully address the multitude of risks that confront us. For decades now, we’ve been destabilizing the world, having failed to imagine the consequences of our actions on our societies and our biosphere, and the way in which they are connected. Now, following this failure and the stark realization of what it has entailed, we need to do just the opposite: rely on the power of imagination to get us out of the holes we’ve dug ourselves into. It is incumbent upon us to imagine the contours of a more equitable and sustainable world. Imagination being boundless, the variety of social, economic, and political solutions is infinite.

With respect to the assertion that there are things we don’t imagine to be socially or politically possible, a recent book shows that nothing is preordained. We are in fact only bound by the power of our own imaginations. In The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow (an anthropologist and an archaeologist) prove this by showing that every imaginable form of social and economic organization has existed from the very beginning of humankind. Over the past 300,000 years, we’ve pursued knowledge, experimentation, happiness, development, freedom, and other human endeavors in myriad different ways. During these times that preceded our modern world, none of the arrangements that we devised to live together exhibited a single point of origin or an invariant pattern. Early societies were peaceful and violent, authoritarian and democratic, patriarchal and matriarchal, slaveholding and abolitionist, some moving between different types of organizations all the time, others not. Antique industrial cities were flourishing at the heart of empires while others existed in the absence of a sovereign entity…(More)”

Mission-oriented innovation

Handbook by Vinnova: “Mission-oriented innovation aims to create change at the system level where everyone involved is involved and drives development. The working method is a tool for achieving jointly set sustainability goals on a broad basis and with great impact.

In this handbook, we tell about Vinnova’s work together with a number of relevant actors to jointly create mission-oriented innovation. You can follow how the actors under 2019-2021 test and develop the working method in the two different areas of food and mobility, respectively. This is a story about how the tool mission-oriented innovation can be used and a guide with concrete tips on how it can be done…(More)”.