Article by Jessica Helfand: “…We are groomed, from an early age, to crave measurement. Notches on walls verify our height. Notes from doctors record our weight. We buy scales and diaries, save report cards and log achievements. As babies become toddlers become adolescents and adults, we take pictures — lots of pictures. Memories registered and milestones passed, we willingly share our data by way of a host of forms that cumulatively present, over a lifetime, as a kind of gold standard. On paper or online, they’re our material witnesses, holding the temporal at bay.

Dora’s material witness is typical of the sorts of records to which all of us are attached, official documents that connect faces to places, snapshots to statistics. Bureaucratic and perfunctory, we seldom stop to question the silent power of these documents, even as they transport our collective selves across time and space. Lacking nuance, devoid of emotion, they nevertheless confer a kind of keen graphic authority, begetting permission, enabling access, presupposing legitimacy, and anticipating a host of needs. Framed by the records that circumscribe that legitimacy — the records and diplomas, ID cards and passports and licenses — the playing field of difference is homogenized by numerical necessity, making all of us, in a sense, prisoners of the indexical.

The pursuit of human metrics has a rich and fascinating history, dating back to the ancient Greeks, who viewed proportion itself as a physical projection of the harmony of the universe. Idealized proportion was synonymous with beauty, a physical expression of divine benevolence. (“The good, of course, is always beautiful,” wrote Plato, “and the beautiful never lacks proportion.”) From Dürer to da Vinci, the notion that humans might aspire to a pure and balanced ideal would find expression in everything from the writings of Vitruvius to the gardens of Le Nôtre to the evolution of the humanist alphabet. To the degree that proportion itself was deemed closer to the divine when realized as an expression of balance and geometry, proportion had everything to do with mathematics in general (and the golden section in particular) and found its most profound expression in the realization of the human form.

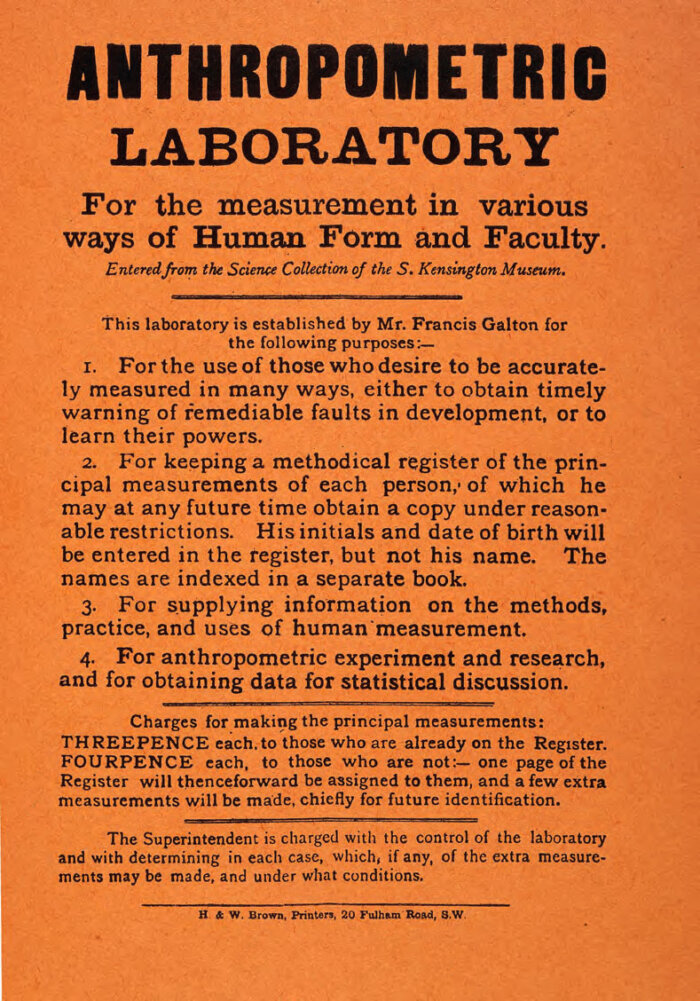

While there is ample evidence to suggest that the urge to measure had its origins in ancient civilizations, the science of bodily measurement was not recognized as a proper professional pursuit until the 19th century. With the advent of industry and the pragmatic concerns with which it was associated — growth projections, profit motives, numerical evidence as approved metrics for evaluation — certain public institutions were perhaps uniquely sensitized to appreciate the value of quantitative data. Statistics as a field of mathematical inquiry gained traction as a discipline thanks in no small part to the scholarship of Sir Francis Galton, whose obsession with counting and measuring everything imaginable (but especially human beings) warrants mention here. His 1851 “Anthropometric Laboratory” — which was included in the International Health Exhibition held in London in 1885 — was an attempt to show the public how human characteristics could be both measured and recorded. Add to this the rise in photography as a promising new technology and the idea of capturing evidence via methodical efforts in data mining was an idea whose time had clearly come….(More)”