Stefaan Verhulst

OECD Report: “Personal health data (PHD) are transforming how individuals engage with health systems, creating new opportunities for trust, innovation, and improving access and quality of care. This report examines how OECD countries enable individuals to access, manage, and share their health information across digital platforms and patient portals. Drawing from in-depth interviews with national authorities in Australia, Denmark, Finland, Japan, Korea, and the United Kingdom, the paper analyses policy, technical, and governance enablers that underpin equitable access to personal health data. It identifies leading practices in interoperability, data architecture, privacy, consent, digital identity, and patient engagement. Countries with mature ecosystems demonstrated consistent public trust frameworks, integration across sectors, and strong legislative foundations balancing privacy with data interoperability and sharing. As healthcare becomes increasingly digital and the availability of patient-generated data grows, ensuring that individuals can securely access and use their own health data will be critical for future-ready, data-driven, and person-centred health systems…(More)”.

Article by Mansoor Al Mansoori and Noura Al Ghaithi: “For more than a decade, global leaders have recognized the rising burden of chronic, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as heart disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer. These conditions are the leading cause of death globally – accounting for 71% of all deaths – and represent the most costly, preventable health challenge of our time.

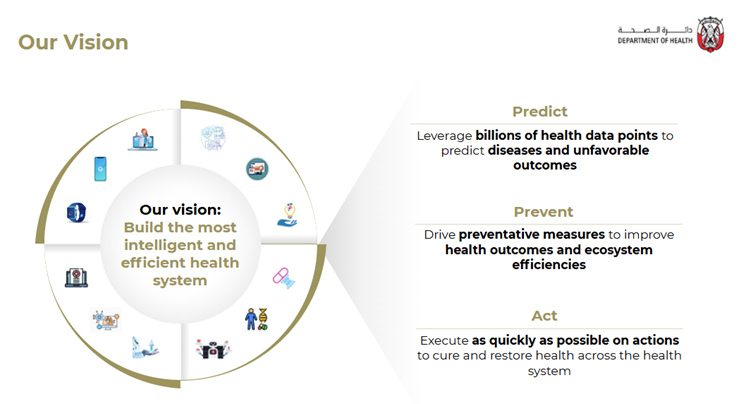

Abu Dhabi, however, is establishing a new global benchmark for health, demonstrating that prevention at population scale is possible. Advances in digitalization, AI, multimodal data and life sciences technology are making it possible to move decisively from reactive “sick care” to predictive, proactive and personalized healthcare…At the core of its digital health transformation lies a unified strategy: Predict, Prevent and Act to Cure and to Restore. This is powered by Abu Dhabi’s Intelligent Health System, which integrates medical records, insurance data, genomics, environmental and lifestyle data into a fully sovereign, privacy-protected ecosystem.

Abu Dhabi’s Predict, Prevent and Act to Cure and to Restore healthy system framework.Image: DOH Abu Dhabi

This infrastructure is powered by platforms like Malaffi, the region’s first health information exchange, connecting 100% of the emirate’s public and private healthcare providers and insurers with real-time access to patient histories, enabling more coordinated, efficient and patient-centred care and reducing system level costs for diagnostics.

Meanwhile, Sahatna, a mobile app used by more than 800,000 residents, empowers the community members to take ownership of their health. It provides secure access to personal health data, enables proactive appointment booking across the ecosystem, instant telehealth consultations, wellness tracking and behavioural nudges toward prevention. This plays a critical role in simplifying personal health, helping to shift the public’s mindset from reactive treatment to self-led prevention…(More)”.

Article by Kathy Talkington: “…Before the advent of vaccines, antibiotics, and modern sanitation, infectious diseases were the leading killers. But today, chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and asthma account for 70% of deaths and 86% of health care expenses in the United States. Yet the clinical data that doctors must report is still largely restricted to infectious diseases.

So, if doctors aren’t required to report chronic disease data and cannot feasibly do so, where can public health agencies turn? One major source is insurance providers. They collect information daily on the types of illnesses that patients have, the treatments being recommended, and the medications being prescribed. Insurance providers use this data to determine reimbursement rates, assess the quality of care, and guide treatment, but public health agencies do not have ready access to this information.

To help overcome this gap, The Pew Charitable Trusts recently launched a project to build data-driven partnerships between state public health agencies and their Medicaid counterparts. Why Medicaid? First, as the nation’s largest single payer, it can provide public health agencies with a large pool of claims data. Second, Medicaid serves people who would benefit most by more effective public health programs, including families with low incomes, people with disabilities, and older adults. And, lastly, Medicaid influences the practices of two critical constituencies: private insurers that contract with Medicaid and the 70% of doctors who accept Medicaid payments…(More)”.

Paper by Chinasa T. Okolo: “The increasing development of machine learning (ML) models and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, particularly generative AI, has dramatically shifted practices around data, spurring the development of new industries centered around data labeling and revealing new forms of exploitation, including illegal data scraping for AI training datasets. These new complexities around data production, refinement, and use have also impacted African countries, elevating a need for comprehensive regulation and enforcement measures. While 38/55 African Union (AU) Member States have existing data protection regulations, there is a wide disparity in the comprehensiveness and quality of these regulations and in the ability of individual countries to enact sufficient protections against data privacy violations. Thus, to enable effective data governance, AU Member States must enact comprehensive data protection regulations and reform existing data governance measures to cover aspects such as data quality, privacy, responsible data sharing, transparency, and data worker labor protections. This paper analyzes data governance measures in Africa, outlines data privacy violations across the continent, and examines regulatory gaps imposed by a lack of comprehensive data governance to outline the sociopolitical infrastructure required to bolster data governance capacity.

This work introduces the RICE Data Governance Framework, which aims to operationalize comprehensive data governance in Africa by outlining best measures for data governance policy

reform, integrating revamped policies, increasing continentalwide cooperation in AI governance, and improving enforcement actions against data privacy violations…(More)”

Paper by Stefaan Verhulst: “We are entering a data winter-a period marked by the growing inaccessibility of data critical for science, governance, and innovation. Just as previous AI winters saw stagnation in artificial intelligence research, today’s data winter is characterized by the enclosure of data behind proprietary, regulatory, and technological barriers. This contraction threatens the capacity for evidence-based policymaking, scientific discovery, and equitable AI development at a moment when data has become society’s most strategic resource. Eight interrelated forces are driving this decline: government open data cutbacks, shifting institutional priorities toward risk aversion, generative AI-induced data hoarding, research data lockdowns, scarcity of high-quality training data, risks of synthetic data substitution, geopolitical fragmentation, and private-sector closure. Together, these trends risk immobilizing data that could otherwise serve the public good. To counteract this trajectory, the paper proposes five strategic interventions: (1) shifting norms and incentives to treat data as essential infrastructure; (2) translating openness commitments into enforceable action; (3) investing in professional data stewardship across sectors; (4) advancing governance innovations such as digital self-determination and social license mechanisms to restore trust; and (5) developing sustainable data commons as shared infrastructures for equitable reuse. The technical means exist, but the collective will is uncertain. The paper concludes by arguing that the coming years will determine whether society builds an open, collaborative data ecosystem-or succumbs to a fragmented, privatized data order…(More)”.

Paper by Federico Bartolomucci & Gianluca Bresolin: “The use of data for social good has received increasing attention from institutions, practitioners and academics in recent years. Data collaboratives are cross-sectoral partnerships that aim to foster the use of data for societal purposes. However, the proliferation of initiatives on the topic of data sharing has created confusion regarding their nature and scope. To advance research on the topic, using existing literature, this paper offers a refinement of the concept of data collaboratives ten years after their first definition. This enables the distinction between data collaboratives and other forms of initiatives such as open platforms and data ecosystems. Through the analysis of a dataset of 171 data collaboratives, the paper proposes an enhanced categorisation that identifies five clusters of data collaboratives. Each cluster is described with a focus on its individual characteristics and development challenges. The holistic approach adopted and the maturity of the field allowed us to gain valuable insights into the domains and scopes that these types of partnership may serve and their potential impact. The results highlight the heterogeneity of initiatives falling under the concept of data collaboratives and the necessity to address their development challenges by either concentrating on a specific cluster or conducting comparative and horizontal studies. These findings also enable comparability and improve the identification of benchmarks, which is a valuable resource for the development of the field…(More)”.

Paper by Francis Gassert, et al: “AI for Nature examines the transformative role of artificial intelligence in understanding and protecting the natural world. The paper outlines how AI can be applied to environmental monitoring, biodiversity mapping, and land-use planning, while also identifying the social, ethical, and governance challenges that accompany these technologies. It calls for collaboration across science, technology, and policy to ensure AI benefits both nature and people…(More)”.

Article by Alonzo Plough and Joel Gurin: “Data-driven, reality-based health science saves lives. Without it, we could not protect people from disease, cure them when they’re sick, or ensure that the places where they live promote good health. In America today, however, an anti-facts movement is eroding the data needed to protect lives.

Already, the Trump administration has dramatically changed how health data is gathered and reported, removed federal websites and datasets, cut staff and funding for health agencies and health research, and diminished our ability to track traditional health outcomes and social determinants of health. The public health community has lost critical data for tracking flu, COVID, sexually transmitted diseases, women’s and children’s health, and more. Thousands of staff at the Department of Health and Human Services have been let go.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has made protecting America’s essential health data a priority. To that end, the foundation supported an expert roundtable in July hosted by the nonprofit Center for Open Data Enterprise (CODE) and the National Conference on Citizenship. CODE has synthesized the results of that roundtable and extensive additional research in a new report, Ensuring the Future of Essential Health Data for All Americans. The report is a timely and comprehensive summary of the sweeping shifts endangering both the health of Americans and the capacity to measure how everyday conditions — like access to food, safe neighborhoods, and jobs — shape health outcomes. It presents five recommendations and several tactics to protect and improve critical health data…(More)”.

Series by UNECE: “The purpose of the Policy Briefs series is to highlight the opportunities and the challenges that AI poses to PPPs and infrastructure throughout the lifecycle of projects. Lower transaction costs for governments and an expedited PPP process would represent a transformational leap in the efficiency and effectiveness of PPPs in support of the SDGs. But such efficiencies need to be measured against the risks associated with the implementation of AI in PPPs and infrastructure projects.

The Policy Briefs are drafted by leading experts under the auspices of the UNECE secretariat and are supplemented by regular webinars or podcasts organised by the UNECE secretariat, engaging various experts from governments, private sector, academia, civil society, and international organisations.

The Policy Briefs series will address both the pros and the cons in implementing AI in PPPs and infrastructure projects, including how AI is already utilised in projects and its potential to predict infrastructure needs, generate reports and analyses data…(More)”.

Report by By Kathrin Frauscher and Kaye Sklar: “Public sector organizations are accelerating their investments in AI technology, and spending big: In the UK, government contracts for AI projects hit £573 million by August 2025, exceeding all of 2024. In the United States, federal agencies committed $5.6 billion to AI between 2022 and 2024. But it’s not just what they buy, it’s how they buy it that will have a huge impact on outcomes.

1. Off-the-shelf AI is winning over custom builds.

Organizations aren’t rushing to buy complex, custom-built AI systems. Instead, right now they are purchasing off-the-shelf licenses for lower-risk efficiency-driven use cases, such as AI-powered writing assistants, data analysis tools, or automated document management systems. Public sector organizations can often use these tools through their existing cloud or productivity platforms.

2. Centralized buying is on the rise.

We see a clear shift toward enterprise-wide AI procurement. Central IT or digital transformation agencies now negotiate contracts for all government departments. The United States, among others, has moved to this model. While central purchasing can promote efficiency and interoperability, this also means that decision-making power is concentrated in fewer hands.

3. AI is sneaking in through side doors.

Not all AI used by the public sector goes through procurement. Government agencies often access AI through free pilots, grants, features built into existing tools, or academic partnerships. This “shadow AI” can help teams move fast, but it means less opportunity for accountability and oversight.

Together, these trends create a growing gap between AI procurement and AI adoption…(More)”.