Stefaan Verhulst

Book by Bruce Schneier and Nathan E. Sanders: “AI is changing democracy. We still get to decide how.

AI’s impact on democracy will go far beyond headline-grabbing political deepfakes and automated misinformation. Everywhere it will be used, it will create risks and opportunities to shake up long-standing power structures.

In this highly readable and advisedly optimistic book, Rewiring Democracy, security technologist Bruce Schneier and data scientist Nathan Sanders cut through the AI hype and examine the myriad ways that AI is transforming every aspect of democracy—for both good and ill.

The authors describe how the sophistication of AI will fulfill demands from lawmakers for more complex legislation, reducing deference to the executive branch and altering the balance of power between lawmakers and administrators. They show how the scale and scope of AI is enhancing civil servants’ ability to shape private-sector behavior, automating either the enforcement or neglect of industry regulations. They also explain how both lawyers and judges will leverage the speed of AI, upending how we think about law enforcement, litigation, and dispute resolution.

Whether these outcomes enhance or degrade democracy depends on how we shape the development and use of AI technologies. Powerful players in private industry and public life are already using AI to increase their influence, and AIs built by corporations don’t deliver the fairness and trust required by democratic governance. But, steered in the right direction, AI’s broad capabilities can augment democratic processes and help citizens build consensus, express their voice, and shake up long-standing power structures.

Democracy is facing new challenges worldwide, and AI has become a part of that. It can inform, empower, and engage citizens. It can also disinform, disempower, and disengage them. The choice is up to us. Schneier and Sanders blaze the path forward, showing us how we can use AI to make democracy stronger and more participatory…(More)”.

Paper by Nils Messerschmidt et al: “E-participation platforms are an important asset for governments in increasing trust and fostering democratic societies. By engaging public and private institutions and individuals, policymakers can make informed and inclusive decisions. However, current approaches of primarily static nature struggle to integrate citizen feedback effectively. Drawing on the Media Richness Theory and applying the Design Science Research method, we explore how a chatbot can address these shortcomings to improve the decision-making abilities for primary stakeholders of e-participation platforms. Leveraging the ”Have Your Say” platform, which solicits feedback on initiatives and regulations by the European Commission, a Large Language Model-based chatbot, called AskThePublic is created, providing policymakers, journalists, researchers, and interested citizens with a convenient channel to explore and engage with citizen input. Evaluating AskThePublic in 11 semi-structured interviews with public sector-affiliated experts, we find that the interviewees value the interactive and structured responses as well as enhanced language capabilities…(More)”

Reading list by Rand: “Interactions with algorithms can have a profoundly adverse and significant impact on the functioning of democratic societies. But what would it look like to design AI and the associated socio-technical systems to improve democracy?

A collection of RAND researchers, graduate students, and outside contributors collaborated to develop a reading list on the topic. This list served as the foundation for lively discussions about how AI and DMDU could be used to steer democracy toward a brighter, more sustainable future.

The collaborators broke these questions into their component parts, and examined them over a period of four weeks…(More)”.

Essay by Antón Barba-Kay: “Most discussions of digital democracy presume, as I’ve mentioned, a confrontation between the vertical boss-man and the horizontal people. What this dichotomy misses is that the character of these figures, as well as of their relationships, has qualitatively changed. Like all legitimate regimes, democracies live by norms—by shared expectations that go unsaid in order to make communication possible. This includes threads of social tapestry like what people feel they can get away with, how far is too far, and where we draw the lines. Norms are forms of communal responsiveness. Yet the deterioration of democratic practices and institutions during the past twenty years has revealed the degree to which democracy relies on a moral infrastructure of habits, rapports, and dispositions toward the word in particular. And whereas our trajectory so far has largely been one in which democratic norms have been gradually burned out by our information environment, the fate of democracy actually requires (pace TikTok) that we try to articulate what the moral infrastructure of this democracy is, how digital practices bear on it, and whether these practices can be harmonized with it.

To bring these lines of thought into focus, I will describe three digital pressures that seem to abrade democratic norms, three ways in which digital technology has been justified, and is even justified as a democratic force, but that are in fact anti-democratic by virtue of reforming our understanding of what we are and how we communicate: Those three are choice, optimization, and neutrality. I pick these because the digital temptation to conflate choice with agency, optimization with judgment, and neutrality with truth especially illuminates the difference between digital and literate democratic norms. But these conflations work only to the extent that we equate what is democratic with what is egalitarian—it is an article of digital faith that these are synonymous. Yet egalitarianism is a property both of democracy and of certain kinds of autocracy. Everything depends on our resisting this equation….

The most successful digital tool for democratic deliberation has been Polis—a platform that has been used in Taiwan to consult a wide public and to help legitimize government policy goals. Polis’s key innovation is that it allows citizens to post comments and to vote on those of others in order to approach consensus, but it does not allow them to reply to each other. One can only “engage” with others’ posts by agreeing, disagreeing, or passing. This eliminates the possibility of trolling and flame wars. It is nonetheless telling that its success as a digital democratic process is predicated on bracketing the exchange of reasons as disruptive. By incentivizing fewer siloed, less complex statements, it solves for a political product at the expense of the process of deliberative speech….(More)”.

Blog by Fernando Monge: “In 2020, Wellington’s city council decided to map 16 kilometers of the city’s streets using GPR and Lidar technologies. They were astounded by what they found. Just in that relatively shorter mileage they identified 100 anomalies – including a collapsed water main. This pilot and an additional study gave them the justification they needed to secure the resources – 4 million dollars from the central government – to launch the pilot for an underground asset map.1

Identifying a need and getting funding to tackle it is one thing. Coordinating across the infrastructure sector is another. Aware of the importance of collaboration for the project’s success, the city council established a technical reference group with representatives from the city, the water entity, electricity and gas distributors, telecommunication providers, contractors and other experts.

Another core piece of the governance framework was finding a neutral entity that would manage the register. This is key in any data sharing scheme. Companies and public entities sharing the data want to trust that whomever is receiving their data will not share it with anyone who shouldn’t have access to it. They also need to be confident of technical security aspects. In the case of the UAR, this intermediary role was played by Digital Built Aotearoa, a neutral not‑for‑profit entity that operates the platform and runs a federated data sharing scheme, ensuring that no one single entity controls all the data.

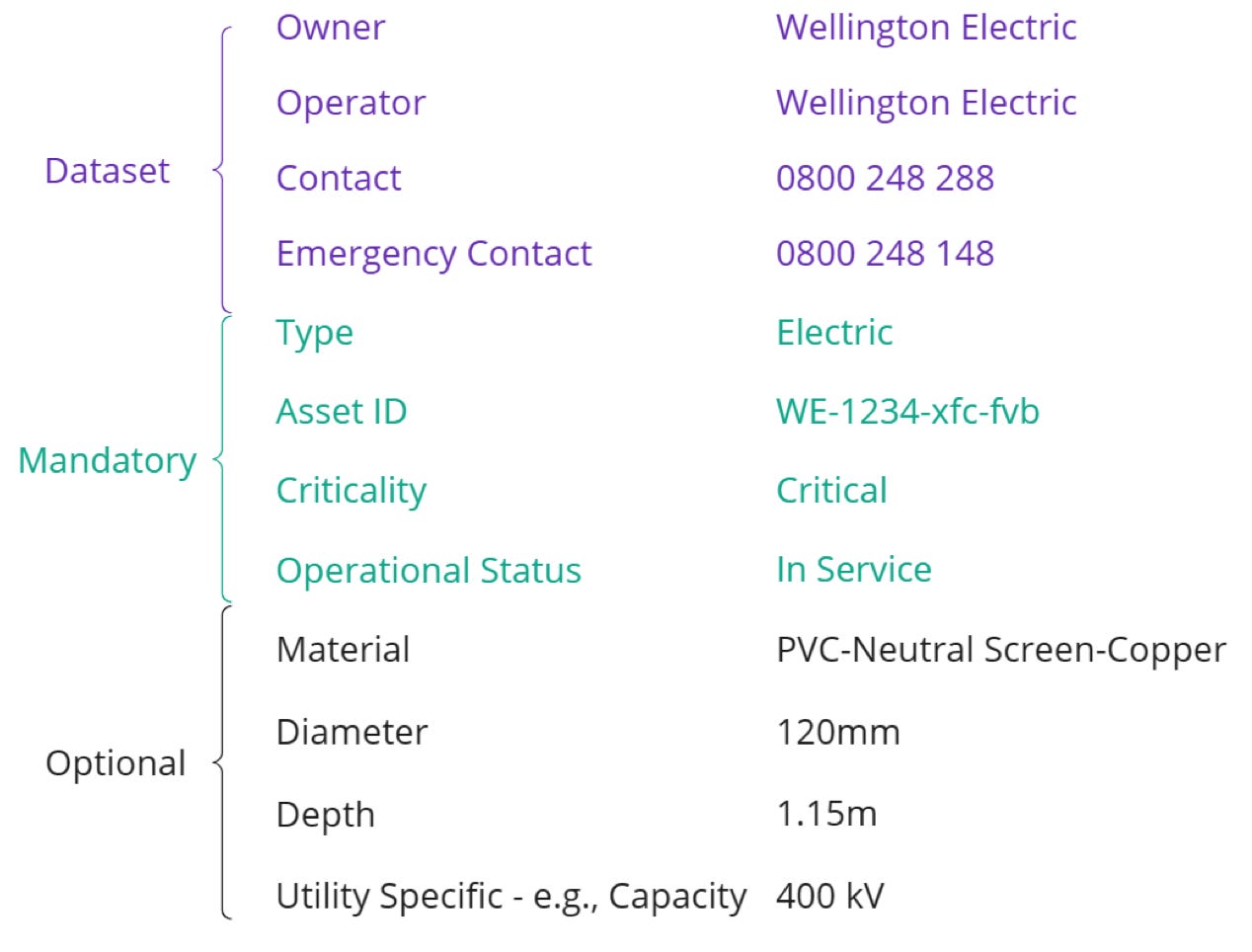

Through this collaboration process – one of the most interesting aspects of the UAR’s experience – partners agreed on the type of information, standards and sharing mechanisms of the UAR. For example, assets’ attributes such as type (water main, sewer, power cable…), ownership, dimension, material, installation data and positional accuracy need to be included in the register. Metadata also describes how each dataset was collected, its refresh rate and usage constraints. See an example of some of the data collected per asset:

The quality of the data is determined based on whether it was derived from existing records or precisely surveyed. Asset owners share it with the platform through APIs or file uploads. Field crews of asset owners or construction companies can also share data directly via a mobile app when they find something while digging…(More)”.

Book by John P. Wihbey: “The large, corporate global platforms networking the world’s publics now host most of the world’s information and communication. Much has been written about social media platforms, and many have argued for platform accountability, responsibility, and transparency. But relatively few works have tried to place platform dynamics and challenges in the context of history, especially with an eye toward sensibly regulating these communications technologies. In Governing Babel, John Wihbey considers the ongoing, high-stakes debate over social media platforms and free speech, and how these companies ought to manage their tremendous power.

Wihbey takes readers on a journey into the high-pressure and controversial world of social media content moderation, looking at issues through relevant cultural, legal, historical, and global lenses. The book addresses a vast challenge—how to create new rules to deal with the ills of our communications and media systems—but the central argument it develops is relatively simple. The idea is that those who create and manage systems for communications hosting user-generated content have both a responsibility to look after their platforms and a duty to respond to problems. They must, in effect, adopt a central response principle that allows their platforms to take reasonable action when potential harms present themselves. And finally, they should be judged, and subject to sanction, according to the good faith and persistence of their efforts…(More)”.

Article by Eli Tan: “The devices are part of an industry known as precision farming, a data-driven approach for optimizing production that is booming with the addition of A.I. and other technologies. Last year, the livestock-monitoring industry alone was valued at more than $5 billion, according to Grand View Research, a market research firm.

Farmers have long used technology to collect and analyze data, with the origins of precision farming dating to the 1990s. In the early 2000s, satellite imagery changed the way farmers determined crop schedules, as did drones and eventually sensors in the fields. Nowadays, if you drive by farms in places like California’s Central Valley, you may not see any humans at all.It is not just dairy farms seeing a change. Elsewhere in the Central Valley, which produces about half of America’s fruits and vegetables, autonomous tractors that use the same sensors as robot taxis and apple-picking tools with A.I. cameras have become popular.

The most common precision farming technology, like GPS maps that track crop yields and auto-steering tractors, are used by 70 percent of large farms today, up from less than 10 percent in the early 2000s, according to Department of Agriculture data.

“The tech is getting faster every year,” said Deepak Joshi, a professor of precision agriculture at Kansas State University. “It used to be we’d have new technologies every few years, and now it’s every six months.”The new products are helping farmers reduce costs as tariffs and inflation raise the prices of farm equipment and feed. They also allow farmers to do more work with fewer people as the Trump administration cracks down on illegal immigration.

Precision farming has boomed as the costs of cameras and sensors have plunged and A.I. models that analyze data have improved, said Charlie Wu, the founder of Orchard Robotics, a farming robotics start-up in San Francisco. Much like the rest of the A.I. industry, agricultural technology is now anchored by chips made by Nvidia, he said…(More)”.

Book by Sigge Winther Nielsen: “The wicked problems of our time – climate change, migration, inequality, productivity, and mental health – remain stubbornly unresolved in Western democracies. It’s time for a new way to puzzle.

This book takes the reader on a journey from London to Berlin, and from Rome to Washington DC and Copenhagen, to discover why modern politics keeps breaking down. We’re tackling twenty-first century problems with twentiethcentury ideas and nineteenth-century institutions.

In search of answers, the author gate-crashes a Conservative party at an English estate, visits a stressed-out German minister at his Mallorcan holiday home, and listens in on power gossip in Washington DC’s restaurant scene. The Puzzle State offers one of the most engaging and thoughtful analyses of Western democracies in recent years. Based on over 100 interviews with top political players, surveys conducted across five countries, and stories of high-profile policy failures, it uncovers a missing link in reform efforts: the absence of ongoing feedback loops between decision-makers and frontline practitioners in schools, hospitals, and companies.

But there is a way forward. The author introduces the concept of the Puzzle State, which uses collective intelligence and AI to (re)connect politicians with the people implementing reforms on the ground. The Puzzle State tackles highprofile wicked problems and enables policies to adapt as they meet messy realities. No one holds all the pieces in the Puzzle State. The feedback loop must cut across all sectors – from civil society to corporations – just like solving a complex puzzle requires commitment, cooperation, and creativity…(More)”.

Article by Jenifer Whiston: “At Free Law Project, we believe the law belongs to everyone. But for too long, the information needed to understand and use the law—especially in civil rights litigation—has been locked behind paywalls, scattered across jurisdictions, or buried in technical complexity.

That’s why we teamed up with the Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse on an exploratory grant from Arnold Ventures: to see how artificial intelligence could help unlock these barriers, making court documents more accessible and legal research more open and accurate.

What We Learned

This six-month project gave us the opportunity to experiment boldly. Together, we researched and tested AI based approaches and tools to:

- Classify legal documents into categories like motions, orders, or opinions.

- Summarize filings and entire cases, turning dense legal text into plain-English explanations.

- Generate structured metadata to make cases easier to track and analyze.

- Trace the path of a legal case as it moves through the court system

- Enable semantic search, allowing users to type questions in everyday language and find relevant cases.

- Build the foundation of an open-source citator, so researchers and advocates can see when cases are overturned, affirmed, or otherwise impacted by later decisions.

These prototypes showed us not only what’s possible, but what’s practical. By testing real AI models on real data, we proved that tools like these can responsibly scale to improve the infrastructure of justice…(More)”.

Report by Rainer Kattel et al: “The four-stage assessment approach for assessing city government dynamic capabilities reflects the complexity of city governments. It blends rigour with usefulness, striving to be both robust and usable, adding value to city governments and those that support their efforts. This report summarises how to assess and compare dynamic capabilities across city governments, provides an assessment of dynamic capabilities in a selected sample set of cities, and sets out future work that will explore how to create an index that can be scaled to thousands of cities and used to effectively build capabilities, positively transforming cities and creating better lives for residents…(More)”.