/ˌmɛkəˈnɪstɪk ˈɛvədəns/

Evidence about either the existence or the nature of a causal mechanism connecting the two; in other words, about the entities and activities mediating the XY relationship (Marchionni and Samuli Reijula, 2018).

There has been mounting pressure on policymakers to adopt and expand the concept of evidence-based policy making (EBP).

In 2017, the U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking issued a report calling for a future in which “rigorous evidence is created efficiently, as a routine part of government operations, and used to construct effective public policy.” The report asserts that modern technology and statistical methods, “combined with transparency and a strong legal framework, create the opportunity to use data for evidence building in ways that were not possible in the past.”

Similarly, the European Commission’s 2015 report on Strengthening Evidence Based Policy Making through Scientific Advice states that policymaking “requires robust evidence, impact assessment and adequate monitoring and evaluation,” emphasizing the notion that “sound scientific evidence is a key element of the policy-making process, and therefore science advice should be embedded at all levels of the European policymaking process.” That same year, the Commission’s Data4Policy program launched a call for contributions to support its research:

“If policy-making is ‘whatever government chooses to do or not to do’ (Th. Dye), then how do governments actually decide? Evidence-based policy-making is not a new answer to this question, but it is constantly challenging both policy-makers and scientists to sharpen their thinking, their tools and their responsiveness.”

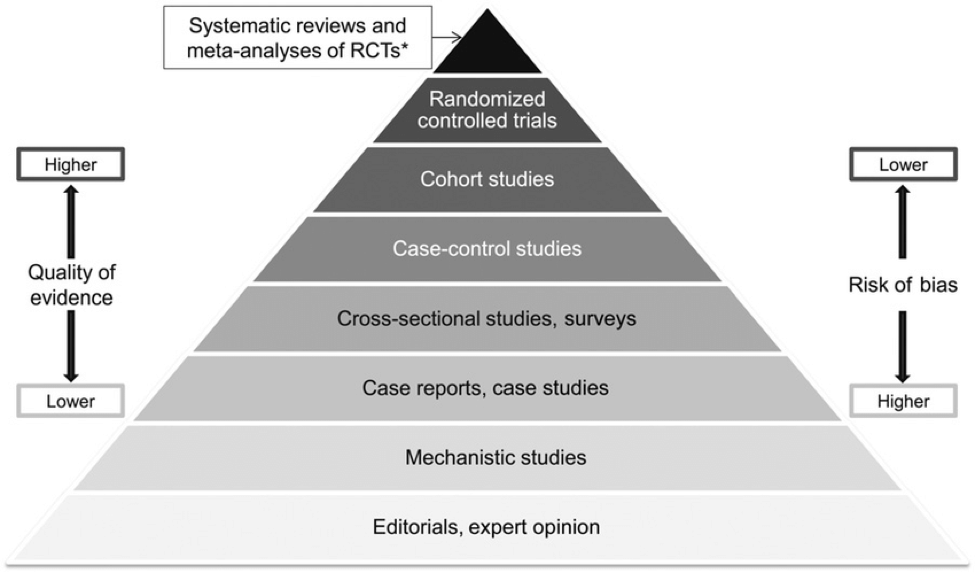

Yet, while the importance and value of EBP are well established, the question of how to establish evidence is often answered by referring to randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, or case reports. According to Caterina Marchionni and Samuli Reijula these answers overlook the important concept of mechanistic evidence.

Their paper takes a deeper dive into the differences between statistical and mechanistic evidence:

“It has recently been argued that successful evidence-based policy should rely on two kinds of evidence: statistical and mechanistic. The former is held to be evidence that a policy brings about the desired outcome, and the latter concerns how it does so.”

The paper further argues that in order to make effective decisions, policymakers must take both statistical and mechanistic evidence into account:

“… whereas statistical studies provide evidence that the policy variable, X, makes a difference to the policy outcome, Y, mechanistic evidence gives information about either the existence or the nature of a causal mechanism connecting the two; in other words, about the entities and activities mediating the XY relationship. Both types of evidence, it is argued, are required to establish causal claims, to design and interpret statistical trials, and to extrapolate experimental findings.”

Ultimately Marchionni and Reijula take a closer look at why introducing research methods that beyond RCTs is crucial for evidence-based policymaking:

“The evidence-based policy (EBP) movement urges policymakers to select policies on the basis of the best available evidence that they work. EBP utilizes evidence-ranking schemes to evaluate the quality of evidence in support of a given policy, which typically prioritize meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials (henceforth RCTs) over other evidence-generating methods.”

They go on to explain that mechanistic evidence has been placed “at the bottom of the evidence hierarchies,” while RCTs have been considered the “gold standard.”

However, the paper argues, mechanistic evidence is in fact as important as statistical evidence:

“… evidence-based policy nearly always involves predictions about the effectiveness of an intervention in populations other than those in which it has been tested. Such extrapolative inferences, it is argued, cannot be based exclusively on the statistical evidence produced by methods higher up in the hierarchies.”

Sources and Further Readings:

- Clarke, Brendan, Gillies, Donald, Illari, Phyllis, Federica Russo, and Jon Williamson. “Mechanisms and the Evidence Hierarchy.” Topoi 33 (2014): 339–360.

- “Evidence-Based Policymaking: What is it? How does it work? What relevance for developing countries?” Overseas Development Institute, 2015.

- Grüne-Yanoff, Till. “Why Behavioural Policy Needs Mechanistic Evidence.” Economics and Philosophy 32 no. 3 (2016).