Introduction to Special Issue of International Organization by

Judith G. Kelley and Beth A. Simmons: “In recent decades, IGOs, NGOs, private firms and even states have begun to regularly package and distribute information on the relative performance of states. From the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index to the Financial Action Task Force blacklist, global performance indicators (GPIs) are increasingly deployed to influence governance globally. We argue that GPIs derive influence from their ability to frame issues, extend the authority of the creator, and — most importantly — to invoke recurrent comparison that stimulates governments’ concerns for their own and their country’s reputation. Their public and ongoing ratings and rankings of states are particularly adept at capturing attention not only at elite policy levels but also among other domestic and transnational actors. GPIs thus raise new questions for research on politics and governance globally. What are the social and political effects of this form of information on discourse, policies and behavior? What types of actors can effectively wield GPIs and on what types of issues? In this symposium introduction, we define GPIs, describe their rise, and theorize and discuss these questions in light of the findings of the symposium contributions…(More)”.

The Remarkable Unresponsiveness of College Students to Nudging And What We Can Learn from It

Paper by Philip Oreopoulos and Uros Petronijevic: “We present results from a five-year effort to design promising online and text-message interventions to improve college achievement through several distinct channels. From a sample of nearly 25,000 students across three different campuses, we find some improvement from coaching-based interventions on mental health and study time, but none of the interventions we evaluate significantly influences academic outcomes (even for those students more at risk of dropping out). We interpret the results with our survey data and a model of student effort. Students study about five to eight hours fewer each week than they plan to, though our interventions do not alter this tendency. The coaching interventions make some students realize that more effort is needed to attain good grades but, rather than working harder, they settle by adjusting grade expectations downwards. Our study time impacts are not large enough for translating into significant academic benefits. More comprehensive but expensive programs appear more promising for helping college students outside the classroom….(More)”

In the Mood for Democracy? Democratic Support as Thermostatic Opinion

Paper by Christopher Claassen: “Public support has long been thought crucial for the survival of democracy. Existing research has argued that democracy moreover appears to create its own demand: the presence of a democratic system coupled with the passage of time produces a public who supports democracy. Using new panel measures of democratic mood varying over 135 countries and up to 30 years, this paper finds little evidence for such a positive feedback effect of democracy on support. Instead, it demonstrates a thermostatic effect: increases in democracy depress democratic mood, while decreases cheer it. Moreover, it is increases in the liberal, counter-majoritarian aspects of democracy, not the majoritarian, electoral aspects that provoke this backlash from citizens. These novel results challenge existing research on support for democracy, but also reconcile this research with the literature on macro-opinion….(More)”.

Truth and Consequences

Sophia Rosenfeld at The Hedgehog Review: “Conventional wisdom has it that for democracy to work, it is essential that we—the citizens—agree in some minimal way about what reality looks like. We are not, of course, all required to think the same way about big questions, or believe the same things, or hold the same values; in fact, it is expected that we won’t. But somehow or other, we need to have acquired some very basic, shared understanding about what causes what, what’s broadly desirable, what’s dangerous, and how to characterize what’s already happened.

Some social scientists call this “public knowledge.” Some, more cynically, call it “serviceable truth” to emphasize its contingent, socially constructed quality. Either way, it is the foundation on which democratic politics—in which no one person or institution has sole authority to determine what’s what and all claims are ultimately revisable—is supposed to rest. It is also imagined to be one of the most exalted products of the democratic process. And to a certain degree, this peculiar, messy version of truth has held its own in modern liberal democracies, including the United States, for most of their history.

Lately, though, even this low-level kind of consensus has come to seem elusive. The issue is not just professional spinners talking about “alternative facts” or the current US president bending the truth and spreading conspiracy theories at every turn, from mass rallies to Twitter rants. The deeper problem stems from the growing sense we all have that, today, even hard evidence of the kind that used to settle arguments about factual questions won’t persuade people whose political commitments have already led them to the opposite conclusion. Rather, citizens now belong to “epistemic tribes”: One person’s truth is another’s hoax or lie. Just look at how differently those of different political leanings interpret the evidence of global warming or the conclusions of the Mueller Report on Russian involvement in the 2016 Trump presidential campaign. Moreover, many of those same people are also now convinced that the boundaries between truth and untruth are, in the end, as subjective as everything else. It is all a matter of perception and spin; nothing is immune, and it doesn’t really matter.

Headed for a Cliff

So what’s happened? Why has assent on even basic factual claims (beyond logically demonstrable ones, like 2 + 2 = 4) become so hard to achieve? Or, to put it slightly differently, why are we—meaning people of varied political persuasions—having so much trouble lately arriving at any broadly shared sense of the world beyond ourselves, and, even more, any consensus on which institutions, methods, or people to trust to get us there? And why, ultimately, do so many of us seem simply to have given up on the possibility of finding some truths in common?

These are questions that seem especially loaded precisely because of the traditionally close conceptual and historical relationship between truth and democracy as social values….(More)”.

From City to Nation: Digital government in Argentina, 2015–2018

Paper by Tanya Filer, Antonio Weiss and Juan Cacace: “In 2015, voters in Argentina elected Mauricio Macri of the centre-right Propuesta Republicana (PRO) as their new President, following a tightly contested race. Macri inherited an office wrought with tensions: an unstable economy; a highly polarised population; and an increasing weariness towards the institutions of governance overall. In this context, his administration hoped to harness the possibilities of digital transformation to make citizens’ interactions with the State more efficient, more accountable, and ‘friendlier’.

Following a successful tenure in the City of Buenos Aires, where Macri had been Mayor, Minister Andrés Ibarra and a digital government team were charged with the project of national digital transformation, taking on projects from a single ‘whole-of-government’ portal to a mobile phone application designed to reduce the incidence of gender-based violence against women. Scaling up digitisation from the city to the national level was, by all accounts, a challenge. By 2018, Argentina had won global acclaim for its progress on key aspects of digital government, but also increasingly recognised the difficulties of digitisation at the national scale. It identified the need, as observed by the OECD, for an overarching strategic plan to manage the scale, diversity and politics of federal-level digital transformation. Based on interviews with key stakeholders, this case discusses the country’s digital modernisation agenda from 2015 to 2018, with a primary focus on service provision projects. It examines the challenges faced in terms of politics and technology, and the lessons that Argentina’s experience offers….(More)”

In Search of Lost Time on YouTube

Laurence Scott at the New Atlantis: “But while there are few things more clearly of-the-moment than our biggest video-sharing site, YouTube is also the closest thing we have invented to a time machine: Its channels open new routes back to the past. Over these years I’ve come to understand that my YouTube, what I make of it, is one of the most melancholy places I’ve ever visited. I find that I turn to it to experience an exquisite kind of sadness, born from its way of restoring lost time only to take it away once more. The scenes and atmospheres of the past that come and go — as copyright infringements are enforced or channels simply subside — are like digital visitations, having the capriciousness and the fragility of all revenants.

history of our era may one day be told through the hungry, wide-angle lens of YouTube. Adding hundreds of hours of footage to its archive every minute, YouTube captures the appetites and deliriums of our times. Historians of the future will be able to trace contemporary ethics in the site’s “community guidelines.” This evolving document records our prohibitions. It defines the territory of acceptable behavior and the scope of our vision, setting limits on what we can permit one another to see. How will the short-lived “Bird Box Challenge” — in which people recorded themselves performing daily tasks blindfolded, endangering themselves and others in imitation of the eponymous film — come to mark our relationship to reality in our increasingly mediated, movie-like world?

The digital era has given more people than ever before the ability to turn into instant videographers, recording life as it occurs simply by holding up a smartphone. Consider the relative rarity of citizen footage of 9/11, compared to how comprehensively that event would have been documented today.With the improving robustness of live-streaming software, it’s not surprising that video-hosting sites such as YouTube and Facebook have become broadcasters of the ever-unfolding moment. Both sites were widely criticized after the mass shooting at a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand in March, which the perpetrator live-streamed on Facebook. The initial stream was viewed live by about two hundred people, but before Facebook removed it, users recorded it and re-uploaded it to Facebook over a million times. They also uploaded it to YouTube: A spokesperson told the Guardian that the site had received an “unprecedented” volume of content showing the horrific event, with the rate reaching a new video uploaded every second. The sites struggled to subdue these gruesome scenes, which nightmarishly returnedmore quickly than their content moderators, both human and automated, could remove them…

But while there are few things more clearly of-the-moment than our biggest video-sharing site, YouTube is also the closest thing we have invented to a time machine: Its channels open new routes back to the past. Over these years I’ve come to understand that my YouTube, what I make of it, is one of the most melancholy places I’ve ever visited. I find that I turn to it to experience an exquisite kind of sadness, born from its way of restoring lost time only to take it away once more. The scenes and atmospheres of the past that come and go — as copyright infringements are enforced or channels simply subside — are like digital visitations, having the capriciousness and the fragility of all revenants….(More)”.

Nudging Us To Health

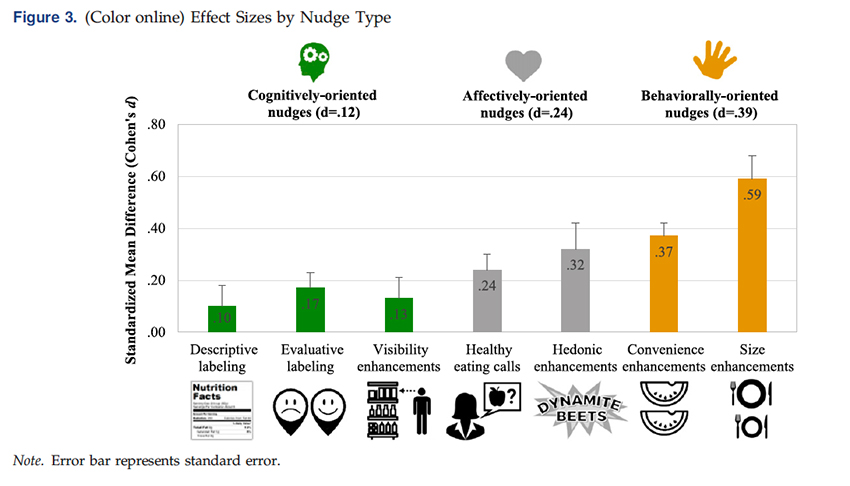

Blog by Chuck Dinerstein: “Policymakers love nudges – predictably altering people’s behavior without forbidding choices or changing economic incentives. That is especially true for our food choices since we all eat, and it is clear that diet does have some effect on our health. The “promise to improve people’s diet at a fraction of the cost of economic incentives or education programs without imposing new taxes or constraints on business or consumers,” is a have my cake and eat it world. A study by the masters of understanding our behavior, the marketers, sheds light on which nudges work best….

Cognitive nudges include those often-invoked nutritional labels or evaluative labels that skip the verbiage and are green for buy, red for put it back on the shelf, and yellow for it’s up to you. Visibility enhancements refer to getting the item into your visual field at the right time and place, like eye-level on the shelf or in the check-out line. Nudges that appeal to our feelings include all the images making food appealing, think food porn, or simple slogans, e.g., “natural,” “healthy choice,” or ”just like mama made.” (Assuming mom was a good cook). As the researchers point out, there are no labels on foods that promote guilt or concern as we see on tobacco’s Surgeon General warnings. Finally, there are behavioral nudges that make one choice easier than another, precut fruits and vegetables, or big utensils for vegetables, and tiny ones for fried chicken. It also includes smaller plates that might look fuller or large drink glasses that are 80% ice

Here is the graphic of their findings:

Graphic by Pierre Chandon

- Nudges do move behavior, although the effect is small, a change of about 124 calories, or in the author’s words “eight fewer teaspoons of sugar.” For those who do not eat sugar by the spoonful, you might consider this to be 1 ½ Jelly Filled Munchkins.

- As the graph shows, appealing to our intellect works the least well, appeals to our emotions are twice as effective, and making it easy to do the “right thing” works the best, five-fold better, than educating us.

- Nudges are better at decreasing bad choices than increasing good ones. “it is easier to make people eat less chocolate cake than to make them eat more vegetables…” In fact, total eating was basically unaffected by nudges, again as the authors write, “this finding is consistent with what we know about the difficulty – perhaps even pointlessness – of hypocaloric diets.”

- The effect of nudges is a lot less when you’re shopping than when you’re eating.

- The effect of nudges in isolation seems more pronounced statistically speaking than when considered in conjunction with where they take place and other contextual information.

- Nudges were equally effective, or ineffective, with adults and children; although you might expect that adults would be more responsive given their presumably better understanding of diet and health

The study makes two points. First, nudges can move behavior a little bit, and the fact that it has few recognized costs means that policymakers will continue to utilize them. Second, it provides an analytic framework highlighting areas where the evidence is scant and could, I suggest, nudge researchers to explore….(More)”.

Foundations of Information Ethics

Book by John T. F. Burgess and Emily J. M. Knox: “As discussions about the roles played by information in economic, political, and social arenas continue to evolve, the need for an intellectual primer on information ethics that also functions as a solid working casebook for LIS students and professionals has never been more urgent. This text, written by a stellar group of ethics scholars and contributors from around the globe, expertly fills that need. Organized into twelve chapters, making it ideal for use by instructors, this volume from editors Burgess and Knox

- thoroughly covers principles and concepts in information ethics, as well as the history of ethics in the information professions;

- examines human rights, information access, privacy, discourse, intellectual property, censorship, data and cybersecurity ethics, intercultural information ethics, and global digital citizenship and responsibility;

- synthesizes the philosophical underpinnings of these key subjects with abundant primary source material to provide historical context along with timely and relevant case studies;

- features contributions from John M. Budd, Paul T. Jaeger, Rachel Fischer, Margaret Zimmerman, Kathrine A. Henderson, Peter Darch, Michael Zimmer, and Masooda Bashir, among others; and

- offers a special concluding chapter by Amelia Gibson that explores emerging issues in information ethics, including discussions ranging from the ethics of social media and social movements to AI decision making…(More)”.

Design Tweak Yields 18 Percent Rise in SNAP Enrollment

Zack Quaintance at Government Technology: “A new study has found that a small human-centered design tweak made by government can increase the number of eligible people who enroll for food benefits.

The study — conducted by the data science firm Civis Analytics and the nonprofit food benefits enrollment advocacy group mRelief — was conducted in Los Angeles County from January to April of this year. It was designed to test a pair of potential improvements. The first was the ability to schedule a call directly with the CalFresh office, which handles food benefits enrollment in California. The second was the ability to schedule a call along with a text reminder to schedule a call. The study was conducted via a randomized control trial that ultimately included about 2,300 people.

What the research found was an 18 percent increase in enrollment within the group that was given the chance to schedule a call. Subsequently, text reminders showed no increase of any significance….(More)”.

What If There Were More Policy Futures Studios?

Essay by Lucy Kimbell: “Unexpected election results are intersecting in new and often disturbing ways with enduring issues such as economic and social inequalities; climate change; global movements of people fleeing war, poverty and environmental change; and the social and cultural consequences of long-term cuts in public funding. These developments are punctuated by dramatic events such as war, terrorist attacks and disasters such as floods, fires and other effects of changes in rainfall and temperature. Many of the available public policy visions of the future fail to connect with people’s day-to-day realities and challenges they face. Where could alternative visions and more effective public policy solutions come from? And what roles can design and futures practices play in constituting these?

For people using design-based and arts-based approaches in relation to social and public policy issues, the practices, structures and processes associated with institutions making public policy present a paradox. On

the one hand, creative methods can enable people to participate in assessing how things are, in ways that are meaningful to them, and imagining how things could be different, and to do so in collaboration with people they might not ordinarily engage with. Workshops and spaces for exploring futures such as design jams, hackathons, digital platforms, exhibitions and co-working hubs can open up a distributed creative capacity for negotiating potentialities in relation to current actualities. The strong emphasis in design on how people experience issues – understanding things on their terms, informed by the principles of ethnography – can open up participation, critique and creativity. Such practices can surface and open up difficult questions about institutions and how they work….(More)”.