Chris Holden and Maynard Holliday at Commons Lab: “Traditional monitoring of arms control treaties, agreements, and commitments has required the use of National Technical Means (NTM)—large satellites, phased array radars, and other technological solutions. NTM was a good solution when the treaties focused on large items for observation, such as missile silos or nuclear test facilities. As the targets of interest have shrunk by orders of magnitude, the need for other, more ubiquitous, sensor capabilities has increased. The rise in web-based, or cloud-based, analytic capabilities will have a significant influence on the future of arms control monitoring and the role of citizen involvement.

Since 1999, the U.S. Department of State has had at its disposal the Key Verification Assets Fund (V Fund), which was established by Congress. The Fund helps preserve critical verification assets and promotes the development of new technologies that support the verification of and compliance with arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament requirements.

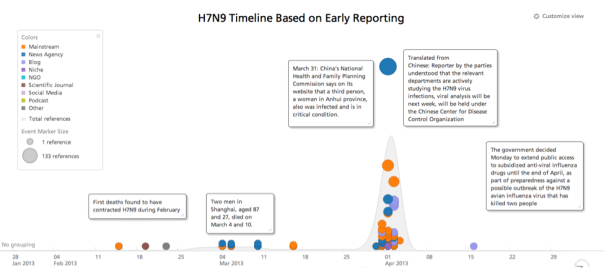

Sponsored by the V Fund to advance web-based analytic capabilities, Sandia National Laboratories, in collaboration with Recorded Future (RF), synthesized open-source data streams from a wide variety of traditional and nontraditional web sources in multiple languages along with topical texts and articles on national security policy to determine the efficacy of monitoring chemical and biological arms control agreements and compliance. The team used novel technology involving linguistic algorithms to extract temporal signals from unstructured text and organize that unstructured text into a multidimensional structure for analysis. In doing so, the algorithm identifies the underlying associations between entities and events across documents and sources over time. Using this capability, the team analyzed several events that could serve as analogs to treaty noncompliance, technical breakout, or an intentional attack. These events included the H7N9 bird flu outbreak in China, the Shanghai pig die-off and the fungal meningitis outbreak in the United States last year.

For H7N9 we found that open source social media were the first to report the outbreak and give ongoing updates. The Sandia RF system was able to roughly estimate lethality based on temporal hospitalization and fatality reporting. For the Shanghai pig die-off the analysis tracked the rapid assessment by Chinese authorities that H7N9 was not the cause of the pig die-off as had been originally speculated. Open source reporting highlighted a reduced market for pork in China due to the very public dead pig display in Shanghai. Possible downstream health effects were predicted (e.g., contaminated water supply and other overall food ecosystem concerns). In addition, legitimate U.S. food security concerns were raised based on the Chinese purchase of the largest U.S. pork producer (Smithfield) because of a fear of potential import of tainted pork into the United States….

To read the full paper, please click here.”

The Social Laboratory

Shane Harris in Foreign Policy: “…, Singapore has become a laboratory not only for testing how mass surveillance and big-data analysis might prevent terrorism, but for determining whether technology can be used to engineer a more harmonious society….Months after the virus abated, Ho and his colleagues ran a simulation using Poindexter’s TIA ideas to see whether they could have detected the outbreak. Ho will not reveal what forms of information he and his colleagues used — by U.S. standards, Singapore’s privacy laws are virtually nonexistent, and it’s possible that the government collected private communications, financial data, public transportation records, and medical information without any court approval or private consent — but Ho claims that the experiment was very encouraging. It showed that if Singapore had previously installed a big-data analysis system, it could have spotted the signs of a potential outbreak two months before the virus hit the country’s shores. Prior to the SARS outbreak, for example, there were reports of strange, unexplained lung infections in China. Threads of information like that, if woven together, could in theory warn analysts of pending crises.

The RAHS system was operational a year later, and it immediately began “canvassing a range of sources for weak signals of potential future shocks,” one senior Singaporean security official involved in the launch later recalled.

The system uses a mixture of proprietary and commercial technology and is based on a “cognitive model” designed to mimic the human thought process — a key design feature influenced by Poindexter’s TIA system. RAHS, itself, doesn’t think. It’s a tool that helps human beings sift huge stores of data for clues on just about everything. It is designed to analyze information from practically any source — the input is almost incidental — and to create models that can be used to forecast potential events. Those scenarios can then be shared across the Singaporean government and be picked up by whatever ministry or department might find them useful. Using a repository of information called an ideas database, RAHS and its teams of analysts create “narratives” about how various threats or strategic opportunities might play out. The point is not so much to predict the future as to envision a number of potential futures that can tell the government what to watch and when to dig further.

The officials running RAHS today are tight-lipped about exactly what data they monitor, though they acknowledge that a significant portion of “articles” in their databases come from publicly available information, including news reports, blog posts, Facebook updates, and Twitter messages. (“These articles have been trawled in by robots or uploaded manually” by analysts, says one program document.) But RAHS doesn’t need to rely only on open-source material or even the sorts of intelligence that most governments routinely collect: In Singapore, electronic surveillance of residents and visitors is pervasive and widely accepted…”

Sharing Data Is a Form of Corporate Philanthropy

Matt Stempeck in HBR Blog: “Ever since the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters was signed in 1999, satellite companies like DMC International Imaging have had a clear protocol with which to provide valuable imagery to public actors in times of crisis. In a single week this February, DMCii tasked its fleet of satellites on flooding in the United Kingdom, fires in India, floods in Zimbabwe, and snow in South Korea. Official crisis response departments and relevant UN departments can request on-demand access to the visuals captured by these “eyes in the sky” to better assess damage and coordinate relief efforts.

Back on Earth, companies create, collect, and mine data in their day-to-day business. This data has quickly emerged as one of this century’s most vital assets. Public sector and social good organizations may not have access to the same amount, quality, or frequency of data. This imbalance has inspired a new category of corporate giving foreshadowed by the 1999 Space Charter: data philanthropy.

The satellite imagery example is an area of obvious societal value, but data philanthropy holds even stronger potential closer to home, where a wide range of private companies could give back in meaningful ways by contributing data to public actors. Consider two promising contexts for data philanthropy: responsive cities and academic research.

The centralized institutions of the 20th century allowed for the most sophisticated economic and urban planning to date. But in recent decades, the information revolution has helped the private sector speed ahead in data aggregation, analysis, and applications. It’s well known that there’s enormous value in real-time usage of data in the private sector, but there are similarly huge gains to be won in the application of real-time data to mitigate common challenges.

What if sharing economy companies shared their real-time housing, transit, and economic data with city governments or public interest groups? For example, Uber maintains a “God’s Eye view” of every driver on the road in a city:

Imagine combining this single data feed with an entire portfolio of real-time information. An early leader in this space is the City of Chicago’s urban data dashboard, WindyGrid. The dashboard aggregates an ever-growing variety of public datasets to allow for more intelligent urban management.

Over time, we could design responsive cities that react to this data. A responsive city is one where services, infrastructure, and even policies can flexibly respond to the rhythms of its denizens in real-time. Private sector data contributions could greatly accelerate these nascent efforts.

Data philanthropy could similarly benefit academia. Access to data remains an unfortunate barrier to entry for many researchers. The result is that only researchers with access to certain data, such as full-volume social media streams, can analyze and produce knowledge from this compelling information. Twitter, for example, sells access to a range of real-time APIs to marketing platforms, but the price point often exceeds researchers’ budgets. To accelerate the pursuit of knowledge, Twitter has piloted a program called Data Grants offering access to segments of their real-time global trove to select groups of researchers. With this program, academics and other researchers can apply to receive access to relevant bulk data downloads, such as an period of time before and after an election, or a certain geographic area.

Humanitarian response, urban planning, and academia are just three sectors within which private data can be donated to improve the public condition. There are many more possible applications possible, but few examples to date. For companies looking to expand their corporate social responsibility initiatives, sharing data should be part of the conversation…

Companies considering data philanthropy can take the following steps:

- Inventory the information your company produces, collects, and analyzes. Consider which data would be easy to share and which data will require long-term effort.

- Think who could benefit from this information. Who in your community doesn’t have access to this information?

- Who could be harmed by the release of this data? If the datasets are about people, have they consented to its release? (i.e. don’t pull a Facebook emotional manipulation experiment).

- Begin conversations with relevant public agencies and nonprofit partners to get a sense of the sort of information they might find valuable and their capacity to work with the formats you might eventually make available.

- If you expect an onslaught of interest, an application process can help qualify partnership opportunities to maximize positive impact relative to time invested in the program.

- Consider how you’ll handle distribution of the data to partners. Even if you don’t have the resources to set up an API, regular releases of bulk data could still provide enormous value to organizations used to relying on less-frequently updated government indices.

- Consider your needs regarding privacy and anonymization. Strip the data of anything remotely resembling personally identifiable information (here are some guidelines).

- If you’re making data available to researchers, plan to allow researchers to publish their results without obstruction. You might also require them to share the findings with the world under Open Access terms….”

Chief Executive of Nesta on the Future of Government Innovation

Interview between Rahim Kanani and Geoff Mulgan, CEO of NESTA and member of the MacArthur Research Network on Opening Governance: “Our aspiration is to become a global center of expertise on all kinds of innovation, from how to back creative business start-ups and how to shape innovations tools such as challenge prizes, to helping governments act as catalysts for new solutions,” explained Geoff Mulgan, chief executive of Nesta, the UK’s innovation foundation. In an interview with Mulgan, we discussed their new report, published in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies, which highlights 20 of the world’s top innovation teams in government. Mulgan and I also discussed the founding and evolution of Nesta over the past few years, and leadership lessons from his time inside and outside government.

Rahim Kanani: When we talk about ‘innovations in government’, isn’t that an oxymoron?

Geoff Mulgan: Governments have always innovated. The Internet and World Wide Web both originated in public organizations, and governments are constantly developing new ideas, from public health systems to carbon trading schemes, online tax filing to high speed rail networks. But they’re much less systematic at innovation than the best in business and science. There are very few job roles, especially at senior levels, few budgets, and few teams or units. So although there are plenty of creative individuals in the public sector, they succeed despite, not because of the systems around them. Risk-taking is punished not rewarded. Over the last century, by contrast, the best businesses have learned how to run R&D departments, product development teams, open innovation processes and reasonably sophisticated ways of tracking investments and returns.

Kanani: This new report, published in partnership with Bloomberg Philanthropies, highlights 20 of the world’s most effective innovation teams in government working to address a range of issues, from reducing murder rates to promoting economic growth. Before I get to the results, how did this project come about, and why is it so important?

Mulgan: If you fail to generate new ideas, test them and scale the ones that work, it’s inevitable that productivity will stagnate and governments will fail to keep up with public expectations, particularly when waves of new technology—from smart phones and the cloud to big data—are opening up dramatic new possibilities. Mayor Bloomberg has been a leading advocate for innovation in the public sector, and in New York he showed the virtues of energetic experiment, combined with rigorous measurement of results. In the UK, organizations like Nesta have approached innovation in a very similar way, so it seemed timely to collaborate on a study of the state of the field, particularly since we were regularly being approached by governments wanting to set up new teams and asking for guidance.

Kanani: Where are some of the most effective innovation teams working on these issues, and how did you find them?

Mulgan: In our own work at Nesta, we’ve regularly sought out the best innovation teams that we could learn from and this study made it possible to do that more systematically, focusing in particular on the teams within national and city governments. They vary greatly, but all the best ones are achieving impact with relatively slim resources. Some are based in central governments, like Mindlab in Denmark, which has pioneered the use of design methods to reshape government services, from small business licensing to welfare. SITRA in Finland has been going for decades as a public technology agency, and more recently has switched its attention to innovation in public services. For example, providing mobile tools to help patients manage their own healthcare. In the city of Seoul, the Mayor set up an innovation team to accelerate the adoption of ‘sharing’ tools, so that people could share things like cars, freeing money for other things. In south Australia the government set up an innovation agency that has been pioneering radical ways of helping troubled families, mobilizing families to help other families.

Kanani: What surprised you the most about the outcomes of this research?

Mulgan: Perhaps the biggest surprise has been the speed with which this idea is spreading. Since we started the research, we’ve come across new teams being created in dozens of countries, from Canada and New Zealand to Cambodia and Chile. China has set up a mobile technology lab for city governments. Mexico City and many others have set up labs focused on creative uses of open data. A batch of cities across the US supported by Bloomberg Philanthropy—from Memphis and New Orleans to Boston and Philadelphia—are now showing impressive results and persuading others to copy them.

Are the Authoritarians Winning?

Review of several books by Michael Ignatieff in the New York Review of Books: “In the 1930s travelers returned from Mussolini’s Italy, Stalin’s Russia, and Hitler’s Germany praising the hearty sense of common purpose they saw there, compared to which their own democracies seemed weak, inefficient, and pusillanimous.

Democracies today are in the middle of a similar period of envy and despondency. Authoritarian competitors are aglow with arrogant confidence. In the 1930s, Westerners went to Russia to admire Stalin’s Moscow subway stations; today they go to China to take the bullet train from Beijing to Shanghai, and just as in the 1930s, they return wondering why autocracies can build high-speed railroad lines seemingly overnight, while democracies can take forty years to decide they cannot even begin. The Francis Fukuyama moment—when in 1989 Westerners were told that liberal democracy was the final form toward which all political striving was directed—now looks like a quaint artifact of a vanished unipolar moment.

For the first time since the end of the cold war, the advance of democratic constitutionalism has stopped. The army has staged a coup in Thailand and it’s unclear whether the generals will allow democracy to take root in Burma. For every African state, like Ghana, where democratic institutions seem secure, there is a Mali, a Côte d’Ivoire, and a Zimbabwe, where democracy is in trouble.

In Latin America, democracy has sunk solid roots in Chile, but in Mexico and Colombia it is threatened by violence, while in Argentina it struggles to shake off the dead weight of Peronism. In Brazil, the millions who took to the streets last June to protest corruption seem to have had no impact on the cronyism in Brasília. In the Middle East, democracy has a foothold in Tunisia, but in Syria there is chaos; in Egypt, plebiscitary authoritarianism rules; and in the monarchies, absolutism is ascendant.

In Europe, the policy elites keep insisting that the remedy for their continent’s woes is “more Europe” while a third of their electorate is saying they want less of it. From Hungary to Holland, including in France and the UK, the anti-European right gains ground by opposing the European Union generally and immigration in particular. In Russia the democratic moment of the 1990s now seems as distant as the brief constitutional interlude between 1905 and 1914 under the tsar….

It is not at all apparent that “governance innovation,” a bauble Micklethwait and Wooldridge chase across three continents, watching innovators at work making government more efficient in Chicago, Sacramento, Singapore, and Stockholm, will do the trick. The problem of the liberal state is not that it lacks modern management technique, good software, or different schemes to improve the “interface” between the bureaucrats and the public. By focusing on government innovation, Micklethwait and Wooldridge assume that the problem is improving the efficiency of government. But what is required is both more radical and more traditional: a return to constitutional democracy itself, to courts and regulatory bodies that are freed from the power of money and the influence of the powerful; to legislatures that cease to be circuses and return to holding the executive branch to public account while cooperating on measures for which there is a broad consensus; to elected chief executives who understand that they are not entertainers but leaders….”

Books reviewed:

Foreign Policy Begins at Home: The Case for Putting America’s House in Order

Restraint: A New Foundation for US Grand Strategy

The Fourth Revolution: The Global Race to Reinvent the State

Reforming Taxation to Promote Growth and Equity

Smart cities from scratch? a socio-technical perspective

Paper by Luís Carvalho in Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society: “This paper argues that contemporary smart city visions based on ITs (information and tele- communication technologies) configure complex socio-technical challenges that can benefit from strategic niche management to foster two key processes: technological learning and societal embedding. Moreover, it studies the extent to which those processes started to unfold in two paradigmatic cases of smart city pilots ‘from scratch’: Songdo (South Korea) and PlanIT Valley (Portugal). The rationale and potentials of the two pilots as arenas for socio-technical experimentation and global niche formation are analysed, as well as the tensions and bottlenecks involved in nurturing socially rich innovation ecosystems and in maintaining social and political support over time.”

Towards a comparative science of cities: using mobile traffic records in New York, London and Hong Kong

Book chapter by S. Grauwin, S. Sobolevsky, S. Moritz, I. Gódor, C. Ratti, to be published in “Computational Approaches for Urban Environments” (Springer Ed.), October 2014: “This chapter examines the possibility to analyze and compare human activities in an urban environment based on the detection of mobile phone usage patterns. Thanks to an unprecedented collection of counter data recording the number of calls, SMS, and data transfers resolved both in time and space, we confirm the connection between temporal activity profile and land usage in three global cities: New York, London and Hong Kong. By comparing whole cities typical patterns, we provide insights on how cultural, technological and economical factors shape human dynamics. At a more local scale, we use clustering analysis to identify locations with similar patterns within a city. Our research reveals a universal structure of cities, with core financial centers all sharing similar activity patterns and commercial or residential areas with more city-specific patterns. These findings hint that as the economy becomes more global, common patterns emerge in business areas of different cities across the globe, while the impact of local conditions still remains recognizable on the level of routine people activity.”

The Emerging Science of Computational Anthropology

Emerging Technology From the arXiv: The increasing availability of big data from mobile phones and location-based apps has triggered a revolution in the understanding of human mobility patterns. This data shows the ebb and flow of the daily commute in and out of cities, the pattern of travel around the world and even how disease can spread through cities via their transport systems.

So there is considerable interest in looking more closely at human mobility patterns to see just how well it can be predicted and how these predictions might be used in everything from disease control and city planning to traffic forecasting and location-based advertising.

Today we get an insight into the kind of detailed that is possible thanks to the work of Zimo Yang at Microsoft research in Beijing and a few pals. These guys start with the hypothesis that people who live in a city have a pattern of mobility that is significantly different from those who are merely visiting. By dividing travelers into locals and non-locals, their ability to predict where people are likely to visit dramatically improves.

Zimo and co begin with data from a Chinese location-based social network called Jiepang.com. This is similar to Foursquare in the US. It allows users to record the places they visit and to connect with friends at these locations and to find others with similar interests.

The data points are known as check-ins and the team downloaded more than 1.3 million of them from five big cities in China: Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Chengdu and Hong Kong. They then used 90 per cent of the data to train their algorithms and the remaining 10 per cent to test it. The Jiapang data includes the users’ hometowns so it’s easy to see whether an individual is checking in in their own city or somewhere else.

The question that Zimo and co want to answer is the following: given a particular user and their current location, where are they most likely to visit in the near future? In practice, that means analysing the user’s data, such as their hometown and the locations recently visited, and coming up with a list of other locations that they are likely to visit based on the type of people who visited these locations in the past.

Zimo and co used their training dataset to learn the mobility pattern of locals and non-locals and the popularity of the locations they visited. The team then applied this to the test dataset to see whether their algorithm was able to predict where locals and non-locals were likely to visit.

They found that their best results came from analysing the pattern of behaviour of a particular individual and estimating the extent to which this person behaves like a local. That produced a weighting called the indigenization coefficient that the researchers could then use to determine the mobility patterns this person was likely to follow in future.

In fact, Zimo and co say they can spot non-locals in this way without even knowing their home location. “Because non-natives tend to visit popular locations, like the Imperial Palace in Beijing and the Bund in Shanghai, while natives usually check in around their homes and workplaces,” they add.

The team say this approach considerably outperforms the mixed algorithms that use only individual visiting history and location popularity. “To our surprise, a hybrid algorithm weighted by the indigenization coefficients outperforms the mixed algorithm accounting for additional demographical information.”

It’s easy to imagine how such an algorithm might be useful for businesses who want to target certain types of travelers or local people. But there is a more interesting application too.

Zimo and co say that it is possible to monitor the way an individual’s mobility patterns change over time. So if a person moves to a new city, it should be possible to see how long it takes them to settle in.

One way of measuring this is in their mobility patterns: whether they are more like those of a local or a non-local. “We may be able to estimate whether a non-native person will behave like a native person after a time period and if so, how long in average a person takes to become a native-like one,” say Zimo and co.

That could have a fascinating impact on the way anthropologists study migration and the way immigrants become part of a local community. This is computational anthropology a science that is clearly in its early stages but one that has huge potential for the future.”

Ref: arxiv.org/abs/1405.7769 : Indigenization of Urban Mobility

Politics or technology – which will save the world?

David Runciman in the Guardian: (Politics by David Runciman is due from Profile ..It is the first in a series of “Ideas in Profile”) “The most significant revolution of the 21st century so far is not political. It is the information technology revolution. Its transformative effects are everywhere. In many places, rapid technological change stands in stark contrast to the lack of political change. Take the United States. Its political system has hardly changed at all in the past 25 years. Even the moments of apparent transformation – such as the election of Obama in 2008 – have only reinforced how entrenched the established order is: once the excitement died away, Obama was left facing the same constrained political choices. American politics is stuck in a rut. But the lives of American citizens have been revolutionised over the same period. The birth of the web and the development of cheap and efficient devices through which to access it have completely altered the way people connect with each other. Networks of people with shared interests, tastes, concerns, fetishes, prejudices and fears have sprung up in limitless varieties. The information technology revolution has changed the way human beings befriend each other, how they meet, date, communicate, medicate, investigate, negotiate and decide who they want to be and what they want to do. Many aspects of our online world would be unrecognisable to someone who was transplanted here from any point in the 20th century. But the infighting and gridlock in Washington would be all too familiar.

This isn’t just an American story. China hasn’t changed much politically since 4 June 1989, when the massacre in Tiananmen Square snuffed out a would-be revolution and secured the current regime’s hold on power. But China itself has been totally altered since then. Economic growth is a large part of the difference. But so is the revolution in technology. A country of more than a billion people, nearly half of whom still live in the countryside, has been transformed by the mobile phone. There are currently over a billion phones in use in China. Ten years ago, fewer than one in 10 Chinese had access to one; today there is nearly one per person. Individuals whose horizons were until very recently constrained by physical geography – to live and die within a radius of a few miles from your birthplace was not unusual for Chinese peasants even into this century – now have access to the wider world. For the present, though maybe not for much longer, the spread of new technology has helped to stifle the call for greater political change. Who needs a political revolution when you’ve got a technological one?

Technology has the power to make politics seem obsolete. The speed of change leaves government looking slow, cumbersome, unwieldy and often irrelevant. It can also make political thinking look tame by comparison with the big ideas coming out of the tech industry. This doesn’t just apply to far‑out ideas about what will soon be technologically possible: intelligent robots, computer implants in the human brain, virtual reality that is indistinguishable from “real” reality (all things that Ray Kurzweil, co-founder of the Google-sponsored Singularity University, thinks are coming by 2030). In this post-ideological age some of the most exotic political visions are the ones that emerge from discussions about tech. You’ll find more radical libertarians and outright communists among computer scientists than among political scientists. Advances in computing have thrown up fresh ways to think about what it means to own something, what it means to share something and what it means to have a private life at all. These are among the basic questions of modern politics. However, the new answers rarely get expressed in political terms (with the exception of occasional debates about civil rights for robots). More often they are expressions of frustration with politics and sometimes of outright contempt for it. Technology isn’t seen as a way of doing politics better. It’s seen as a way of bypassing politics altogether.

In some circumstances, technology can and should bypass politics. The advent of widespread mobile phone ownership has allowed some of the world’s poorest citizens to wriggle free from the trap of failed government. In countries that lack basic infrastructure – an accessible transport network, a reliable legal system, a usable banking sector – phones enable people to create their own networks of ownership and exchange. In Africa, a grassroots, phone-based banking system has sprung up that for the first time permits money transfers without the physical exchange of cash. This makes it possible for the inhabitants of desperately poor and isolated rural areas to do business outside of their local communities. Technology caused this to happen; government didn’t. For many Africans, phones are an escape route from the constrained existence that bad politics has for so long mired them in.

But it would be a mistake to overstate what phones can do. They won’t rescue anyone from civil war. Africans can use their phones to tell the wider world of the horrors that are still taking place in some parts of the continent – in South Sudan, in Eritrea, in the Niger Delta, in the Central African Republic, in Somalia. Unfortunately the world does not often listen, and nor do the soldiers who are doing the killing. Phones have not changed the basic equation of political security: the people with the guns need a compelling reason not to use them. Technology by itself doesn’t give them that reason. Equally, technology by itself won’t provide the basic infrastructure whose lack it has provided a way around. If there are no functioning roads to get you to market, a phone is a godsend when you have something to sell. But in the long run, you still need the roads. In the end, only politics can rescue you from bad politics…”

Democracy and open data: are the two linked?

Molly Shwartz at R-Street: “Are democracies better at practicing open government than less free societies? To find out, I analyzed the 70 countries profiled in the Open Knowledge Foundation’s Open Data Index and compared the rankings against the 2013 Global Democracy Rankings. As a tenet of open government in the digital age, open data practices serve as one indicator of an open government. Overall, there is a strong relationship between democracy and transparency.

Using data collected in October 2013, the top ten countries for openness include the usual bastion-of-democracy suspects: the United Kingdom, the United States, mainland Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

There are, however, some noteworthy exceptions. Germany ranks lower than Russia and China. All three rank well above Lithuania. Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Nepal all beat out Belgium. The chart (below) shows the democracy ranking of these same countries from 2008-2013 and highlights the obvious inconsistencies in the correlation between democracy and open data for many countries.

There are many reasons for such inconsistencies. The implementation of open-government efforts – for instance, opening government data sets – often can be imperfect or even misguided. Drilling down to some of the data behind the Open Data Index scores reveals that even countries that score very well, such as the United States, have room for improvement. For example, the judicial branch generally does not publish data and houses most information behind a pay-wall. The status of legislation and amendments introduced by Congress also often are not available in machine-readable form.

As internationally recognized markers of political freedom and technological innovation, open government initiatives are appealing political tools for politicians looking to gain prominence in the global arena, regardless of whether or not they possess a real commitment to democratic principles. In 2012, Russia made a public push to cultivate open government and open data projects that was enthusiastically endorsed by American institutions. In a June 2012 blog post summarizing a Russian “Open Government Ecosystem” workshop at the World Bank, one World Bank consultant professed the opinion that open government innovations “are happening all over Russia, and are starting to have genuine support from the country’s top leaders.”

Given the Russian government’s penchant for corruption, cronyism, violations of press freedom and increasing restrictions on public access to information, the idea that it was ever committed to government accountability and transparency is dubious at best. This was confirmed by Russia’s May 2013 withdrawal of its letter of intent to join the Open Government Partnership. As explained by John Wonderlich, policy director at the Sunlight Foundation:

While Russia’s initial commitment to OGP was likely a surprising boon for internal champions of reform, its withdrawal will also serve as a demonstration of the difficulty of making a political commitment to openness there.

Which just goes to show that, while a democratic government does not guarantee open government practices, a government that regularly violates democratic principles may be an impossible environment for implementing open government.

A cursory analysis of the ever-evolving international open data landscape reveals three major takeaways:

- Good intentions for government transparency in democratic countries are not always effectively realized.

- Politicians will gladly pay lip-service to the idea of open government without backing up words with actions.

- The transparency we’ve established can go away quickly without vigilant oversight and enforcement.”