Paper by Geoff Mulgan and Vincent Straub: The world is struggling to govern data. The challenge is to reduce abuses of all kinds, enhance accountability and improve ethical standards, while also ensuring that the maximum public and private value can also be derived from data.

Despite many predictions to the contrary the world of commercial data is dominated by powerful organisations. By contrast, there are few institutions to protect the public interest and those that do exist remain relatively weak. This paper argues that new institutions—an ecosystem of trust—are needed to ensure that uses of data are trusted and trustworthy. It advocates the creation of different kinds of data trust to fill this gap. It argues:

- That we need, but currently lack, institutions that are good at thinking through, discussing, and explaining the often complex trade-offs that need to be made about data.

- That the task of creating trust is different in different fields. Overly generic solutions will be likely to fail.

- That trusts need to be accountable—in some cases to individual members where there is a direct relationship with individuals giving consent, in other cases to the broader public.

- That we should expect a variety of types of data trust to form—some sharing data; some managing synthetic data; some providing a research capability; some using commercial data and so on. The best analogy is finance which over time has developed a very wide range of types of institution and governance.

This paper builds on a series of Nesta think pieces on data and knowledge commons published over the last decade and current practical projects that explore how data can be mobilised to improve healthcare, policing, the jobs market and education. It aims to provide a framework for designing a new family of institutions under the umbrella title of data trusts, tailored to different conditions of consent, and different patterns of private and public value. It draws on the work of many others (including the work of GovLab and the Open Data Institute).

Introduction

The governance of personal data of all kinds has recently moved from being a very marginal specialist issue to one of general concern. Too much data has been misused, lost, shared, sold or combined with little involvement of the people most affected, and little ethical awareness on the part of the organisations in charge.

The most visible responses have been general ones—like the EU’s GDPR. But these now need to be complemented by new institutions that can be generically described as ‘data trusts’.

In current practice the term ‘trust’ is used to describe a very wide range of institutions. These include private trusts, a type of legal structure that holds and makes decisions about assets, such as property or investments, and involves trustors, trustees, and beneficiaries. There are also public trusts in fields like education with a duty to provide a public benefit. Examples include the Nesta Trust and the National Trust. There are trusts in business (e.g. to manage pension funds). And there are trusts in the public sector, such as the BBC Trust and NHS Foundation Trusts with remits to protect the public interest, at arms length from political decisions.

It’s now over a decade since the first data trusts were set up as private initiatives in response to anxieties about abuse. These were important pioneers though none achieved much scale or traction.

Now a great deal of work is underway around the world to consider what other types of trust might be relevant to data, so as to fill the governance vacuum—handling everything from transport data to personalised health, the internet of things to school records, and recognising the very different uses of data—by the state for taxation or criminal justice etc.; by academia for research; by business for use and resale; and to guide individual choices. This paper aims to feed into that debate.

1. The twin problems: trust and value

Two main clusters of problem are coming to prominence. The first cluster of problems involve misuseand overuse of data; the second set of problems involves underuse of data.

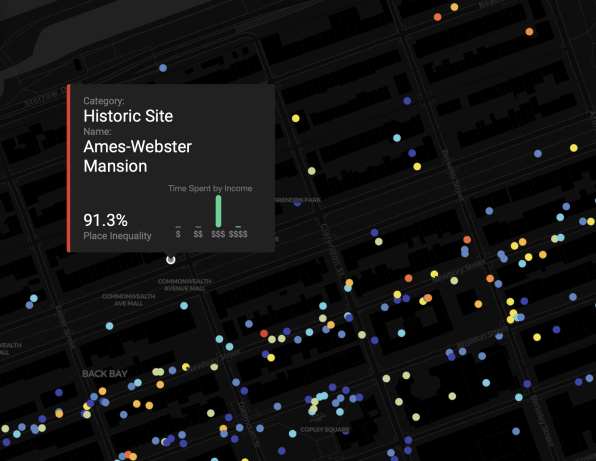

1.1. Lack of control fuels distrust

The first problem is a lack of control and agency—individuals feel unable to control data about their own lives (from Facebook links and Google searches to retail behaviour and health) and communities are unable to control their own public data (as in Sidewalk labs and other smart city projects that attempted to privatise public data). Lack of control leads to the risk of abuses of privacy, and a wider problem of decreasing trust—which survey evidence from the Open Data Institute (ODI) shows is key in determining the likelihood consumers will share their personal data (although this varies across countries). The lack of transparency regarding how personal data is then used to train algorithms making decisions only adds to the mistrust.

1.2 Lack of trust leads to a deficit of public value

The second, mirror cluster of problems concern value. Flows of data promise a lot: better ways to assess problems, understand options, and make decisions. But current arrangements make it hard for individuals to realise the greatest value from their own data, and they make it even harder for communities to safely and effectively aggregate, analyse and link data to solve pressing problems, from health and crime to mobility. This is despite the fact that many consumers are prepared to make trade-offs: to share data if it benefits themselves and others—a 2018 Nesta poll found, for example, that 73 per cent of people said they would share their personal data in an effort to improve public services if there was a simple and secure way of doing it. A key reason for the failure to maximise public value is the lack of institutions that are sufficiently trusted to make judgements in the public interest.

Attempts to answer these problems sometimes point in opposite directions—the one towards less free flow, less linking of data, the other towards more linking and combination. But any credible policy responses have to address both simultaneously.

2. The current landscape

The governance field was largely empty earlier this decade. It is now full of activity, albeit at an early stage. Some is legislative—like GDPR and equivalents being considered around the world. Some is about standards—like Verify, IHAN and other standards intended to handle secure identity. Some is more entrepreneurial—like the many Personal Data Stores launched over the last decade, from Mydexto SOLID, Citizen-me to digi.me. Some are experiments like the newly launched Amsterdam Data Exchange (Amdex) and the UK government’s recently announced efforts to fund data trust pilots to tackle wildlife conservation, working with the ODI. Finally, we are now beginning to see new institutions within government to guide and shape activity, notably the new Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation.

Many organisations have done pioneering work, including the ODI in the UK and NYU GovLab with its work on data collaboratives. At Nesta, as part of the Europe-wide DECODE consortium, we are helping to develop new tools to give people control of their personal data while the Next Generation Internet (NGI) initiative is focused on creating a more inclusive, human-centric and resilient internet—with transparency and privacy as two of the guiding pillars.

The task of governing data better brings together many elements, from law and regulation to ethics and standards. We are just beginning to see more serious discussion about tax and data—from the proposals to tax digital platforms turnover to more targeted taxes of data harvesting in public places or infrastructures—and more serious debate around regulation. This paper deals with just one part of this broader picture: the role of institutions dedicated to curating data in the public interest….(More)”.