Evgeny Morozov in MIT Technology Review: “Intellectually, at least, it’s clear what needs to be done: we must confront the question not only in the economic and legal dimensions but also in a political one, linking the future of privacy with the future of democracy in a way that refuses to reduce privacy either to markets or to laws. What does this philosophical insight mean in practice?

First, we must politicize the debate about privacy and information sharing. Articulating the existence—and the profound political consequences—of the invisible barbed wire would be a good start. We must scrutinize data-intensive problem solving and expose its occasionally antidemocratic character. At times we should accept more risk, imperfection, improvisation, and inefficiency in the name of keeping the democratic spirit alive.

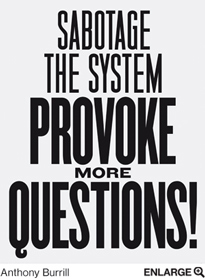

Second, we must learn how to sabotage the system—perhaps by refusing to self-track at all. If refusing to record our calorie intake or our whereabouts is the only way to get policy makers to address the structural causes of problems like obesity or climate change—and not just tinker with their symptoms through nudging—information boycotts might be justifiable. Refusing to make money off your own data might be as political an act as refusing to drive a car or eat meat. Privacy can then reëmerge as a political instrument for keeping the spirit of democracy alive: we want private spaces because we still believe in our ability to reflect on what ails the world and find a way to fix it, and we’d rather not surrender this capacity to algorithms and feedback loops.

Third, we need more provocative digital services. It’s not enough for a website to prompt us to decide who should see our data. Instead it should reawaken our own imaginations. Designed right, sites would not nudge citizens to either guard or share their private information but would reveal the hidden political dimensions to various acts of information sharing. We don’t want an electronic butler—we want an electronic provocateur. Instead of yet another app that could tell us how much money we can save by monitoring our exercise routine, we need an app that can tell us how many people are likely to lose health insurance if the insurance industry has as much data as the NSA, most of it contributed by consumers like us. Eventually we might discern such dimensions on our own, without any technological prompts.

Finally, we have to abandon fixed preconceptions about how our digital services work and interconnect. Otherwise, we’ll fall victim to the same logic that has constrained the imagination of so many well-meaning privacy advocates who think that defending the “right to privacy”—not fighting to preserve democracy—is what should drive public policy. While many Internet activists would surely argue otherwise, what happens to the Internet is of only secondary importance. Just as with privacy, it’s the fate of democracy itself that should be our primary goal.