Paper by Chris Norval, Jennifer Cobbe and Jatinder Singh: “As the IoT becomes increasingly ubiquitous, concerns are being raised about how IoT systems are being built and deployed. Connected devices will generate vast quantities of data, which drive algorithmic systems and result in real-world consequences. Things will go wrong, and when they do, how do we identify what happened, why they happened, and who is responsible? Given the complexity of such systems, where do we even begin?

This chapter outlines aspects of accountability as they relate to IoT, in the context of the increasingly interconnected and data-driven nature of such systems. Specifically, we argue the urgent need for mechanisms – legal, technical, and organisational – that facilitate the review of IoT systems. Such mechanisms work to support accountability, by enabling the relevant stakeholders to better understand, assess, interrogate and challenge the connected environments that increasingly pervade our world….(More)”

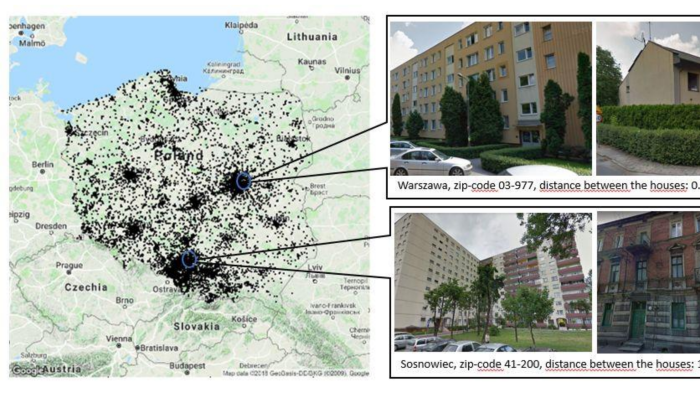

How a Google Street View image of your house predicts your risk of a car accident

MIT Technology Review: “Google Street View has become a surprisingly useful way to learn about the world without stepping into it. People use it to plan journeys, to explore holiday destinations, and to virtually stalk friends and enemies alike.

But researchers have found more insidious uses. In 2017 a team of researchers used the images to study the distribution of car types in the US and then used that data to determine the demographic makeup of the country. It turns out that the car you drive is a surprisingly reliable proxy for your income level, your education, your occupation, and even the way you vote in elections.

Now a different group has gone even further. Łukasz Kidziński at Stanford University in California and Kinga Kita-Wojciechowska at the University of Warsaw in Poland have used Street View images of people’s houses to determine how likely they are to be involved in a car accident. That’s valuable information that an insurance company could use to set premiums.

The result raises important questions about the way personal information can leak from seemingly innocent data sets and whether organizations should be able to use it for commercial purposes.

Insurance data

The researchers’ method is straightforward. They began with a data set of 20,000 records of people who had taken out car insurance in Poland between 2013 and 2015. These were randomly selected from the database of an undisclosed insurance company.

Each record included the address of the policyholder and the number of damage claims he or she made during the 2013–’15 period. The insurer also shared its own prediction of future claims, calculated using its state-of-the-art risk model that takes into account the policyholder’s zip code and the driver’s age, sex, claim history, and so on.

The question that Kidziński and Kita-Wojciechowska investigated is whether they could make a more accurate prediction using a Google Street View image of the policyholder’s house….(More)”.

Geospatial Data Market Study

Study by Frontier Economics: “Frontier Economics was commissioned by the Geospatial Commission to carry out a detailed economic study of the size, features and characteristics of the UK geospatial data market. The Geospatial Commission was established within the Cabinet Office in 2018, as an independent, expert committee responsible for setting the UK’s Geospatial Strategy and coordinating public sector geospatial activity. The Geospatial Commission’s aim is to unlock the significant economic, social and environmental opportunities offered by location data. The UK’s Geospatial Strategy (2020) sets out how the UK can unlock the full power of location data and take advantage of the significant economic, social and environmental opportunities offered by location data….

Like many other forms of data, the value of geospatial data is not limited to the data creator or data user. Value from using geospatial data can be subdivided into several different categories, based on who the value accrues to:

Direct use value: where value accrues to users of geospatial data. This could include government using geospatial data to better manage public assets like roadways.

Indirect use value: where value is also derived by indirect beneficiaries who interact with direct users. This could include users of the public assets who benefit from better public service provision.

Spillover use value: value that accrues to others who are not a direct data user or indirect beneficiary. This could, for example, include lower levels of emissions due to improvement management of the road network by government. The benefits of lower emissions are felt by all of society even those who do not use the road network.

As the value from geospatial data does not always accrue to the direct user of the data, there is a risk of underinvestment in geospatial technology and services. Our £6 billion estimate of turnover for a subset of geospatial firms in 2018 does not take account of these wider economic benefits that “spill over” across the UK economy, and generate additional value. As such, the value that geospatial data delivers is likely to be significantly higher than we have estimated and is therefore an area for potential future investment….(More)”.

A qualitative study of big data and the opioid epidemic: recommendations for data governance

Paper by Elizabeth A. Evans, Elizabeth Delorme, Karl Cyr & Daniel M. Goldstein: “The opioid epidemic has enabled rapid and unsurpassed use of big data on people with opioid use disorder to design initiatives to battle the public health crisis, generally without adequate input from impacted communities. Efforts informed by big data are saving lives, yielding significant benefits. Uses of big data may also undermine public trust in government and cause other unintended harms….

We conducted focus groups and interviews in 2019 with 39 big data stakeholders (gatekeepers, researchers, patient advocates) who had interest in or knowledge of the Public Health Data Warehouse maintained by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Concerns regarding big data on opioid use are rooted in potential privacy infringements due to linkage of previously distinct data systems, increased profiling and surveillance capabilities, limitless lifespan, and lack of explicit informed consent. Also problematic is the inability of affected groups to control how big data are used, the potential of big data to increase stigmatization and discrimination of those affected despite data anonymization, and uses that ignore or perpetuate biases. Participants support big data processes that protect and respect patients and society, ensure justice, and foster patient and public trust in public institutions. Recommendations for ethical big data governance offer ways to narrow the big data divide (e.g., prioritize health equity, set off-limits topics/methods, recognize blind spots), enact shared data governance (e.g., establish community advisory boards), cultivate public trust and earn social license for big data uses (e.g., institute safeguards and other stewardship responsibilities, engage the public, communicate the greater good), and refocus ethical approaches.

Using big data to address the opioid epidemic poses ethical concerns which, if unaddressed, may undermine its benefits. Findings can inform guidelines on how to conduct ethical big data governance and in ways that protect and respect patients and society, ensure justice, and foster patient and public trust in public institutions….(More)”

Social license for the use of big data in the COVID-19 era

Commentary by James A. Shaw, Nayha Sethi & Christine K. Cassel: “… Social license refers to the informal permissions granted to institutions such as governments or corporations by members of the public to carry out a particular set of activities. Much of the literature on the topic of social license has arisen in the field of natural resources management, emphasizing issues that include but go beyond environmental stewardship4. In their seminal work on social license in the pulp and paper industry, Gunningham et al. defined social license as the “demands and expectations” placed on organizations by members of civil society which “may be tougher than those imposed by regulation”; these expectations thereby demand actions that go beyond existing legal rules to demonstrate concern for the interests of publics. We use the plural term “publics” as opposed to the singular “public” to illustrate that stakeholder groups to which organizations must appeal are often diverse and varied in their assessments of whether a given organizational activity is acceptable6. Despite the potentially fragmented views of various publics, the concept of social license is considered in a holistic way (either an organization has it or does not). Social license is closely related to public trust, and where publics view a particular institution as trustworthy it is more likely to have social license to engage in activities such as the collection and use of personal data7.

The question of how the leaders of an organization might better understand whether they have social license for a particular set of activities has also been addressed in the literature. In a review of literature on social license, Moffat et al. highlighted disagreement in the research community about whether social license can be accurately measured4. Certain groups of researchers emphasize that because of the intangible nature of social license, accurate measurement will never truly be possible. Others propose conceptual models of the determinants of social license, and establish surveys that assess those determinants to indicate the presence or absence of social license in a given context. However, accurate measurement of social license remains a point of debate….(More)”.

An Open-Source Tool to Accelerate Scientific Knowledge Discovery

Mozilla: “Timely and open access to novel outputs is key to scientific research. It allows scientists to reproduce, test, and build on one another’s work — and ultimately unlock progress.

The most recent example of this is the research into COVID-19. Much of the work was published in open access journals, swiftly reviewed and ultimately improving our understanding of how to slow the spread and treat the disease. Although this rapid increase in scientific publications is evident in other domains too, we might not be reaping the benefits. The tools to parse and combine this newly created knowledge have roughly remained the same for years.

Today, Mozilla Fellow Kostas Stathoulopoulos is launching Orion — an open-source tool to illuminate the science behind the science and accelerate knowledge discovery in the life sciences. Orion enables users to monitor progress in science, visually explore the scientific landscape, and search for relevant publications.

Orion collects, enriches and analyses scientific publications in the life sciences from Microsoft Academic Graph.

Users can leverage Orion’s views to interact with the data. The Exploration view shows all of the academic publications in a three-dimensional visualization. Every particle is a paper and the distance between them signifies their semantic similarity; the closer two particles are, the more semantically similar. The Metrics view visualizes indicators of scientific progress and how they have changed over time for countries and thematic topics. The Search view enables the users to search for publications by submitting either a keyword or a longer query, for example, a sentence or a paragraph of a blog they read online….(More)”.

The Razor’s Edge: Liberalizing the Digital Surveillance Ecosystem

Report by CNAS: “The COVID-19 pandemic is accelerating global trends in digital surveillance. Public health imperatives, combined with opportunism by autocratic regimes and authoritarian-leaning leaders, are expanding personal data collection and surveillance. This tendency toward increased surveillance is taking shape differently in repressive regimes, open societies, and the nation-states in between.

China, run by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is leading the world in using technology to enforce social control, monitor populations, and influence behavior. Part of maximizing this control depends on data aggregation and a growing capacity to link the digital and physical world in real time, where online offenses result in brisk repercussions. Further, China is increasing investments in surveillance technology and attempting to influence the patterns of technology’s global use through the export of authoritarian norms, values, and governance practices. For example, China champions its own technology standards to the rest of the world, while simultaneously peddling legislative models abroad that facilitate access to personal data by the state. Today, the COVID-19 pandemic offers China and other authoritarian nations the opportunity to test and expand their existing surveillance powers internally, as well as make these more extensive measures permanent.

Global swing states are already exhibiting troubling trends in their use of digital surveillance, including establishing centralized, government-held databases and trading surveillance practices with authoritarian regimes. Amid the pandemic, swing states like India seem to be taking cues from autocratic regimes by mandating the download of government-enabled contact-tracing applications. Yet, for now, these swing states appear responsive to their citizenry and sensitive to public agitation over privacy concerns.

Today, the COVID-19 pandemic offers China and other authoritarian nations the opportunity to test and expand their existing surveillance powers internally, as well as make these more extensive measures permanent.

Open societies and democracies can demonstrate global surveillance trends similar to authoritarian regimes and swing states, including the expansion of digital surveillance in the name of public safety and growing private sector capabilities to collect and analyze data on individuals. Yet these trends toward greater surveillance still occur within the context of pluralistic, open societies that feature ongoing debates about the limits of surveillance. However, the pandemic stands to shift the debate in these countries from skepticism over personal data collection to wider acceptance. Thus far, the spectrum of responses to public surveillance reflects the diversity of democracies’ citizenry and processes….(More)”.

Selected Readings on Data Portability

By Juliet McMurren, Andrew Young, and Stefaan G. Verhulst

As part of an ongoing effort to build a knowledge base for the field of improving governance through technology, The GovLab publishes a series of Selected Readings, which provide an annotated and curated collection of recommended works on themes such as open data, data collaboration, and civic technology.

In this edition, we explore selected literature on data portability.

To suggest additional readings on this or any other topic, please email info@thelivinglib.org. All our Selected Readings can be found here.

Context

Data today exists largely in silos, generating problems and inefficiencies for the individual, business and society at large. These include:

- difficulty switching (data) between competitive service providers;

- delays in sharing data for important societal research initiatives;

- barriers for data innovators to reuse data that could generate insights to inform individuals’ decision making; and

- inhibitions to scale data donation.

Data portability — the principle that individuals have a right to obtain, copy, and reuse their own personal data and to transfer it from one IT platform or service to another for their own purposes — is positioned as a solution to these problems. When fully implemented, it would make data liquid, giving individuals the ability to access their own data in a usable and transferable format, transfer it from one service provider to another, or donate data for research and enhanced data analysis by those working in the public interest.

Some companies, including Google, Apple, Twitter and Facebook, have sought to advance data portability through initiatives like the Data Transfer Project, an open source software project designed to facilitate data transmittals. Newly enacted data protection legislation such as Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (2018) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (2018) give data holders a right to data portability. However, despite the legal and technical advances made, many questions toward scaling up data liquidity and portability responsibly and systematically remain. These new data rights have generated complex and as yet unanswered questions about the limits of data ownership, the implications for privacy, security and intellectual property rights, and the practicalities of how, when, and to whom data can be transferred.

In this edition of the GovLab’s Selected Readings series, we examine the emerging literature on data portability to provide a foundation for future work on the value proposition of data portability. Readings are listed in alphabetical order.

Selected readings

Cho, Daegon, Pedro Ferreira, and Rahul Telang, The Impact of Mobile Number Portability on Price and Consumer Welfare (2016)

- In this paper, the authors analyze how Mobile Number Portability (MNP) — the ability for consumers to maintain their phone number when changing providers, thus reducing switching costs — affected the relationship between switching costs, market price and consumer surplus after it was introduced in most European countries in the early 2000s.

- Theory holds that when switching costs are high, market leaders will enjoy a substantial advantage and are able to keep prices high. Policy makers will therefore attempt to decrease switching costs to intensify competition and reduce prices to consumers.

- The study reviewed quarterly data from 47 wireless service providers in 15 EU countries between 1999 and 2006. The data showed that MNP simultaneously decreased market price by over four percent and increased consumer welfare by an average of at least €2.15 per person per quarter. This increase amounted to a total of €880 million per quarter across the 15 EU countries analyzed in this paper and accounted for 15 percent of the increase in consumer surplus observed over this time.

CtrlShift, Data Mobility: The data portability growth opportunity for the UK economy (2018)

- Commissioned by the UK Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), this study was intended to identify the potential of personal data portability for the UK economy.

- Its scope went beyond the legal right to data portability envisaged by the GDPR, to encompass the current state of personal data portability and mobility, requirements for safe and secure data sharing, and the potential economic benefits through stimulation of innovation, productivity and competition.

- The report concludes that increased personal data mobility has the potential to be a vital stimulus for the development of the digital economy, driving growth by empowering individuals to make use of their own data and consent to others using it to create new data-driven services and technologies.

- However, the report concludes that there are significant challenges to be overcome, and new risks to be addressed, before the value of personal data can be realized. Much personal data remains locked in organizational silos, and systemic issues related to data security and governance and the uneven sharing of benefits need to be resolved.

Data Guidance and Future of Privacy Forum, Comparing Privacy Laws: GDPR v. CCPA (2018)

- This paper compares the provisions of the GDPR with those of the California Consumer Privacy Act (2018).

- Both article 20 of the GDPR and section 1798 of the CCPA recognize a right to data portability. Both also confer on data subjects the right to receive data from controllers free of charge upon request, and oblige controllers to create mechanisms to provide subjects with their data in portable and reusable form so that it can be transmitted to third parties for reuse.

- In the CCPA, the right to data portability is an extension of the right to access, and only confers on data subjects the right to apply for data collected within the past 12 months and have it delivered to them. The GDPR does not impose a time limit, and allows data to be transferred from one data controller to another, but limits the right to automatically collected personal data provided by the data subject themselves through consent or contract.

Data Transfer Project, Data Transfer Project Overview and Fundamentals (2018)

- The paper presents an overview of the goals, principles, architecture, and system components of the Data Transfer Project. The intent of the DTP is to increase the number of services offering data portability and provide users with the ability to transfer data directly in and out of participating providers through systems that are easy and intuitive to use, private and secure, reciprocal between services, and focused on user data. The project, which is supported by Microsoft, Google, Twitter and Facebook, is an open-source initiative that encourages the participation of other providers to reduce the infrastructure burden on providers and users.

- In addition to benefits to innovation, competition, and user choice, the authors point to benefits to security, through allowing users to backup, organize, or archive their data, recover from account hijacking, and retrieve their data from deprecated services.

- The DTP’s remit was to test concepts and feasibility for the transfer of specific types of user data between online services using a system of adapters to transfer proprietary formats into canonical formats that can be used to transfer data while allowing providers to maintain control over the security of their service. While not resolving all formatting or support issues, this approach would allow substantial data portability and encourage ecosystem sustainability.

Deloitte, How to Flourish in an Uncertain Future: Open Banking(2017)

- This report addresses the innovative and disruptive potential of open banking, in which data is shared between members of the banking ecosystem at the authorization of the customer, with the potential to increase competition and facilitate new products and services. In the resulting marketplace model, customers could use a single banking interface to access products from multiple players, from established banks to newcomers and fintechs.

- The report’s authors identify significant threats to current banking models. Banks that failed to embrace open banking could be relegated to a secondary role as an infrastructure provider, while third parties — tech companies, fintech, and price comparison websites — take over the customer relationship.

- The report identifies four overlapping operating models banks could adopt within an open banking model: full service providers, delivering proprietary products through their own interface with little or no third-party integration; utilities, which provide other players with infrastructure without customer-facing services; suppliers, which offer proprietary products through third-party interfaces; and interfaces,which provide distribution services through a marketplace interface. To retain market share, incumbents are likely to need to adopt a combination of these roles, offering their own products and services and those of third parties through their own and others’ interfaces.

Digital Competition Expert Panel Unlocking Digital Competition(2019)

- This report captures the findings of the UK Digital Competition Expert Panel, which was tasked in 2018 with considering opportunities and challenges the digital economy might pose for competition and competition policy and to recommend any necessary changes. The panel focused on the impact of big players within the sector, appropriate responses to mergers or anticompetitive practices, and the impact on consumers.

- The panel found that the digital economy is creating many benefits, but that digital markets are subject to tipping, in which emerging winners can scoop much of the market. This concentration can give rise to substantial costs, especially to consumers, and cannot be solved by competition alone. However, government policy and regulatory solutions have limitations, including the slowness of policy change, uneven enforcement and profound informational asymmetries between companies and government.

- The panel proposed the creation of a digital markets unit that would be tasked with developing a code of competitive conduct, enabling greater personal data mobility and systems designed with open standards, and advancing access to non-personal data to reduce barriers to market entry.

- The panel’s model of data mobility goes beyond data portability, which involves consumers being able to request and transfer their own data from one provider to another. Instead, the panel recommended empowering consumers to instigate transfers of data between a business and a third party in order to access price information, compare goods and services, or access tailored advice and recommendations. They point to open banking as an example of how this could function in practice.

- It also proposed updating merger policy to make it more forward-looking to better protect consumers and innovation and preserve the competitiveness of the market. It recommended the creation of antitrust policy that would enable the implementation of interim measures to limit damage to competition while antitrust cases are in process.

Egan, Erin, Charting a Way Forward: Data Portability and Privacy(2019)

- This white paper by Facebook’s VP and Chief Privacy Officer, Policy, represents an attempt to advance the conversation about the relationship between data portability, privacy, and data protection. The author sets out five key questions about data portability: what is it, whose and what data should be portable, how privacy should be protected in the context of portability, and where responsibility for data misuse or improper protection should lie.

- The paper finds that definitions of data portability still remain imprecise, particularly with regard to the distinction between data portability and data transfer. In the interest of feasibility and a reasonable operational burden on providers, it proposes time limits on providers’ obligations to make observed data portable.

- The paper concludes that there are strong arguments both for and against allowing users to port their social graph — the map of connections between that user and other users of the service — but that the key determinant should be a capacity to ensure the privacy of all users involved. Best-practice data portability protocols that would resolve current differences of approach as to what, how and by whom information should be made available would help promote broader portability, as would resolution of liability for misuse or data exposure.

Engels, Barbara, Data portability among online platforms (2016)

- The article examines the effects on competition and innovation of data portability among online platforms such as search engines, online marketplaces, and social media, and how relations between users, data, and platform services change in an environment of data portability.

- The paper finds that the benefits to competition and innovation of portability are greatest in two kinds of environments: first, where platforms offer complementary products and can realize synergistic benefits by sharing data; and secondly, where platforms offer substitute or rival products but the risk of anti-competitive behaviour is high, as for search engines.

- It identifies privacy and security issues raised by data portability. Portability could, for example, allow an identity fraudster to misuse personal data across multiple platforms, compounding the harm they cause.

- It also suggests that standards for data interoperability could act to reduce innovation in data technology, encouraging data controllers to continue to use outdated technologies in order to comply with inflexible, government-mandated standards.

Graef, Inge, Martin Husovec and Nadezhda Purtova, Data Portability and Data Control: Lessons for an Emerging Concept in EU Law (2018)

- This paper situates the data portability right conferred by the GDPR within rights-based data protection law. The authors argue that the right to data portability should be seen as a new regulatory tool aimed at stimulating competition and innovation in data-driven markets.

- The authors note the potential for conflicts between the right to data portability and the intellectual property rights of data holders, suggesting that the framers underestimated the potential impact of such conflicts on copyright, trade secrets and sui generis database law.

- Given that the right to data portability is being replicated within consumer protection law and the regulation of non-personal data, the authors argue framers of these laws should consider the potential for conflict and the impact of such conflict on incentives to innovate.

Mohsen, Mona Omar and Hassan A. Aziz The Blue Button Project: Engaging Patients in Healthcare by a Click of a Button (2015)

- This paper provides a literature review on the Blue Button initiative, an early data portability project which allows Americans to access, view or download their health records in a variety of formats.

- Originally launched through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs in 2010, the Blue Button initiative had expanded to more than 500 organizations by 2014, when the Department of Health and Human Services launched the Blue Button Connector to facilitate both patient access and development of new tools.

- The Blue Button has enabled the development of tools such as the Harvard-developed Growth-Tastic app, which allows parents to check their child’s growth by submitting their downloaded pediatric health data. Pharmacies across the US have also adopted the Blue Button to provide patients with access to their prescription history.

More than Data and Mission: Smart, Got Data? The Value of Energy Data to Customers (2016)

- This report outlines the public value of the Green Button, a data protocol that provides customers with private and secure access to their energy use data collected by smart meters.

- The authors outline how the use of the Green Button can help states meet their energy and climate goals by enabling them to structure renewables and other distributed energy resources (DER) such as energy efficiency, demand response, and solar photovoltaics. Access to granular, near real time data can encourage innovation among DER providers, facilitating the development of applications like “virtual energy audits” that identify efficiency opportunities, allowing customers to reduce costs through time-of-use pricing, and enabling the optimization of photovoltaic systems to meet peak demand.

- Energy efficiency receives the greatest boost from initiatives like the Green Button, with studies showing energy savings of up to 18 percent when customers have access to their meter data. In addition to improving energy conservation, access to meter data could improve the efficiency of appliances by allowing devices to trigger sleep modes in response to data on usage or price. However, at the time of writing, problems with data portability and interoperability were preventing these benefits from being realized, at a cost of tens of millions of dollars.

- The authors recommend that commissions require utilities to make usage data available to customers or authorized third parties in standardized formats as part of basic utility service, and tariff data to developers for use in smart appliances.

MyData, Understanding Data Operators (2020)

- MyData is a global movement of data users, activists and developers with a common goal to empower individuals with their personal data to enable them and their communities to develop knowledge, make informed decisions and interact more consciously and efficiently.

- This introductory paper presents the state of knowledge about data operators, trusted data intermediaries that provide infrastructure for human-centric personal data management and governance, including data sharing and transfer. The operator model allows data controllers to outsource issues of legal compliance with data portability requirements, while offering individual users a transparent and intuitive way to manage the data transfer process.

- The paper examines use cases from 48 “proto-operators” from 15 countries who fulfil some of the functions of an operator, albeit at an early level of maturity. The paper finds that operators offer management of identity authentication, data transaction permissions, connections between services, value exchange, data model management, personal data transfer and storage, governance support, and logging and accountability. At the heart of these functions is the need for minimum standards of data interoperability.

- The paper reviews governance frameworks from the general (legislative) to the specific (operators), and explores proto-operator business models. In keeping with an emerging field, business models are currently unclear and potentially unsustainable, and one of a number of areas, including interoperability requirements and governance frameworks, that must still be developed.

National Science and Technology Council Smart Disclosure and Consumer Decision Making: Report of the Task Force on Smart Disclosure (2013)

- This report summarizes the work and findings of the 2011–2013 Task Force on Smart Disclosure: Information and Efficiency, an interagency body tasked with advancing smart disclosure, through which data is made more available and accessible to both consumers and innovators.

- The Task Force recognized the capacity of smart disclosure to inform consumer choices, empower them through access to useful personal data, enable the creation of new tools, products and services, and promote efficiency and growth. It reviewed federal efforts to promote smart disclosure within sectors and in data types that crosscut sectors, such as location data, consumer feedback, enforcement and compliance data and unique identifiers. It also surveyed specific public-private partnerships on access to data, such as the Blue and Green Button and MyData initiatives in health, energy and education respectively.

- The Task Force reviewed steps taken by the Federal Government to implement smart disclosure, including adoption of machine readable formats and standards for metadata, use of APIs, and making data available in an unstructured format rather than not releasing it at all. It also reviewed “choice engines” making use of the data to provide services to consumers across a range of sectors.

- The Task Force recommended that smart disclosure should be a core component of efforts to institutionalize and operationalize open data practices, with agencies proactively identifying, tagging, and planning the release of candidate data. It also recommended that this be supported by a government-wide community of practice.

Nicholas, Gabriel Taking It With You: Platform Barriers to Entry and the Limits of Data Portability (2020)

- This paper considers whether, as is often claimed, data portability offers a genuine solution to the lack of competition within the tech sector.

- It concludes that current regulatory approaches to data portability, which focus on reducing switching costs through technical solutions such as one-off exports and API interoperability, are not sufficient to generate increased competition. This is because they fail to address other barriers to entry, including network effects, unique data access, and economies of scale.

- The author proposes an alternative approach, which he terms collective portability, which would allow groups of users to coordinate the transfer of their data to a new platform. This model raises questions about how such collectives would make decisions regarding portability, but would enable new entrants to successfully target specific user groups and scale rapidly without having to reach users one by one.

OECD, Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data: Reconciling Risks and Benefits for Data Re-use across Societies (2019)

- This background paper to a 2017 expert workshop on risks and benefits of data reuse considers data portability as one strategy within a data openness continuum that also includes open data, market-based B2B contractual agreements, and restricted data-sharing agreements within research and data for social good applications.

- It considers four rationales offered for data portability. These include empowering individuals towards the “informational self-determination” aspired to by GDPR, increased competition within digital and other markets through reductions in information asymmetries between individuals and providers, switching costs, and barriers to market entry; and facilitating increased data flows.

- The report highlights the need for both syntactic and semantic interoperability standards to ensure data can be reused across systems, both of which may be fostered by increased rights to data portability. Data intermediaries have an important role to play in the development of these standards, through initiatives like the Data Transfer Project, a collaboration which brought together Facebook, Google, Microsoft, and Twitter to create an open-source data portability platform.

Personal Data Protection Commission Singapore Response to Feedback on the Public Consultation on Proposed Data Portability and Data Innovation Provisions (2020)

- The report summarizes the findings of the 2019 PDPC public consultation on proposals to introduce provisions on data portability and data innovation in Singapore’s Personal Data Protection Act.

- The proposed provision would oblige organizations to transmit an individual’s data to another organization in a commonly used machine-readable format, upon the individual’s request. The obligation does not extend to data intermediaries or organizations that do not have a presence in Singapore, although data holders may choose to honor those requests.

- The obligation would apply to electronic data that is either provided by the individual or generated by the individual’s activities in using the organization’s service or product, but not derived data created by the processing of other data by the data holder. Respondents were concerned that including derived data could harm organizations’ competitiveness.

- Respondents were concerned about how to honour data portability requests where the data of third parties was involved, as in the case of a joint account holder, for example. The PDPC opted for a “balanced, reasonable, and pragmatic approach,” allowing data involving third parties to be ported where it was under the requesting individual’s control, was to be used for domestic and personal purposes, and related only to the organization’s product or service.

Quinn, Paul Is the GDPR and Its Right to Data Portability a Major Enabler of Citizen Science? (2018)

- This article explores the potential of data portability to advance citizen science by enabling participants to port their personal data from one research project to another. Citizen science — the collection and contribution of large amounts of data by private individuals for scientific research — has grown rapidly in response to the development of new digital means to capture, store, organize, analyze and share data.

- The GDPR right to data portability aids citizen science by requiring transfer of data in machine-readable format and allowing data subjects to request its transfer to another data controller. This requirement of interoperability does not amount to compatibility, however, and data thus transferred would probably still require cleaning to be usable, acting as a disincentive to reuse.

- The GDPR’s limitation of transferability to personal data provided by the data subject excludes some forms of data that might possess significant scientific potential, such as secondary personal data derived from further processing or analysis.

- The GDPR right to data portability also potentially limits citizen science by restricting the grounds for processing data to which the right applies to data obtained through a subject’s express consent or through the performance of a contract. This limitation excludes other forms of data processing described in the GDPR, such as data processing for preventive or occupational medicine, scientific research, or archiving for reasons of public or scientific interest. It is also not clear whether the GDPR compels data controllers to transfer data outside the European Union.

Wong, Janis and Tristan Henderson, How Portable is Portable? Exercising the GDPR’s Right to Data Portability (2018)

- This paper presents the results of 230 real-world requests for data portability in order to assess how — and how well — the GDPR right to data portability is being implemented. The authors were interested in establishing the kinds of file formats that were returned in response to requests, and to identify practical difficulties encountered in making and interpreting requests, over a three month period beginning on the day the GDPR came into effect.

- The findings revealed continuing problems around ensuring portability for both data controllers and data subjects. Of the 230 requests, only 163 were successfully completed.

- Data controllers frequently had difficulty understanding the requirements of GDPR, providing data in incomplete or inappropriate formats: only 40 percent of the files supplied were in a fully compliant format. Additionally, some data controllers were confused between the right to data portability and other rights conferred by the GDPR, such as the right to access or erasure.

Make good use of big data: A home for everyone

Paper by Khaled Moustafa in Cities: “The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic should teach us some lessons at health, environmental and human levels toward more fairness, human cohesion and environmental sustainability. At a health level, the pandemic raises the importance of housing for everyone particularly vulnerable and homeless people to protect them from the disease and against other similar airborne pandemics. Here, I propose to make good use of big data along with 3D construction printers to construct houses and solve some major and pressing housing needs worldwide. Big data can be used to determine how many people do need accommodation and 3D construction printers to build houses accordingly and swiftly. The combination of such facilities- big data and 3D printers- can help solve global housing crises more efficiently than traditional and unguided construction plans, particularly under environmental and major health crises where health and housing are tightly interrelated….(More)”.

Health Data Privacy under the GDPR: Big Data Challenges and Regulatory Responses

Book edited by Maria Tzanou: “The growth of data collecting goods and services, such as ehealth and mhealth apps, smart watches, mobile fitness and dieting apps, electronic skin and ingestible tech, combined with recent technological developments such as increased capacity of data storage, artificial intelligence and smart algorithms have spawned a big data revolution that has reshaped how we understand and approach health data. Recently the COVID-19 pandemic has foregrounded a variety of data privacy issues. The collection, storage, sharing and analysis of health- related data raises major legal and ethical questions relating to privacy, data protection, profiling, discrimination, surveillance, personal autonomy and dignity.

This book examines health privacy questions in light of the GDPR and the EU’s general data privacy legal framework. The GDPR is a complex and evolving body of law that aims to deal with several technological and societal health data privacy problems, while safeguarding public health interests and addressing its internal gaps and uncertainties. The book answers a diverse range of questions including: What role can the GDPR play in regulating health surveillance and big (health) data analytics? Can it catch up with the Internet age developments? Are the solutions to the challenges posed by big health data to be found in the law? Does the GDPR provide adequate tools and mechanisms to ensure public health objectives and the effective protection of privacy? How does the GDPR deal with data that concern children’s health and academic research?

By analysing a number of diverse questions concerning big health data under the GDPR from various different perspectives, this book will appeal to those interested in privacy, data protection, big data, health sciences, information technology, the GDPR, EU and human rights law….(More)”.